- Monthly horizon for the S&P 500 suggests more upside

- Are bond yields too high… I offer a good comparison; and

- Another great book to help you better understand (and manage) risk

Whilst the S&P 500 posted a negative week – it was a strong month for equities.

The Index managed to add 4.8% for the month – hitting an intra-month record high of 5339

Perhaps completely enamored by all things AI (more on this in my conclusion) – investors basically shrugged off sharply higher yields and a series of disappointing inflation prints to push prices higher.

What could go wrong?

At the end of every month – it pays to extend our time horizon to the (less noisy) monthly chart.

And whilst the weekly chart is useful – it tends to whip around (i.e., giving us more false signals)

Longer-term trends (and investments) are often better examined using this lens.

Let’s take a look…

Monthly Horizon

As our chart shows below – the S&P 500 reversed the pull-back from April.

June 1st 2024

- January: +1.59%

- February: +5.18%

- March: +3.10%

- April: -4.16%

- May: +4.80%

In addition, it’s been 7 months since we have seen anything near a 10% pullback.

Therefore, those who have not maintained ‘some’ long exposure have probably been caught out.

As an aside, a work colleague asked me this week when the market was going to pull back (as they’re mostly in cash)

My answer was I have no clue... adding it may not for the rest of the year?

“What?” was the response.

And whilst I still expect a pullback in the realm of 10% before then – there’s every possibility it keeps going higher.

From there, they asked “… well if it’s going higher – do I buy here?”

I said that would not be my recommendation.

I explained I felt that’s a lower probability bet… as I think the chances of downside risk outweigh the possible upside gain.

Needless to say they walked away a little annoyed… as saying “be patient” was not the response they wanted.

Two Technical Arguments Suggest Upside

1. Monthly RSI – Not Yet Overbought

If we refer to the middle window – we see the Relative Strength Index (RSI)

The upper limit (in red) has a value of ~78 (vs the standard (overbought) value of 70).

For example, if we look back at the price action for the S&P 500 over the past 20 years – we see this indicator will often exceed 78 before exhaustion.

At the time of writing, the monthly RSI trades at 66.

I’ve penciled in a couple of orange lines as to where it could go if the market continues to march higher.

But as I explained to my frustrated colleague – this is not an attractive entry point if you don’t already have exposure.

And for those who are already long – I would stay with it here.

Now if we look at the blue line – that represents ~46 on the RSI.

Notice when the market has retraced double-digits over the past 20 years – this the level on the RSI where it found buying support.

Put another way, it did not need to plunge to a level “below 30” to suggest it was an attractive entry (which is what we saw in 2008)

Using that metric – my recommendation would wait until we see the monthly RSI in the realm of 46 before adding back long exposure.

It might be a few months – I don’t know – but it’s likely to pay off.

Over the past 20 years – this has proven to offer great risk/reward over the longer-term.

2. Monthly MACD – Has Not Rolled Over

The other important observation is what we see with the monthly-MACD (lower window)

Typically when this indicator crosses over (i.e. the blue-line cuts back below the red-line) – stocks typically lose ground.

For example, this indicator crossed over in Feb 2022 and Feb 2020. And look what followed…

We also saw it cross lower in Oct 2018; and also Nov 2007 (well ahead of the near 50% correction)

There are many examples like this which proved to be reliable signals of (strong) market reversals.

However at the time of writing, the monthly MACD continues to move higher.

This also suggests there could be more room to run.

And if the Fed are to cut rates (which seems increasingly unlikely given inflation) and/or bond yields are to come down – this would support the case for higher equities.

Speaking of which…

Are Bond Yields Too High?

Regular readers will know I choose to add exposure to the US 10-year treasury when it exceeds 4.5%

My logic here is I think bond yields will come down (in time) – and if true – bonds see strong capital appreciation.

Bond prices trade inversely to yields.

And in the meantime, I am happy being paid the income.

Now, on the topic of bond yields, I read some interesting analysis from Jim Paulsen this week suggesting bond yields could be too high.

According to Paulsen:

“One way to judge the level of bond yields is to compare them to the yield offerings of alternative investments.

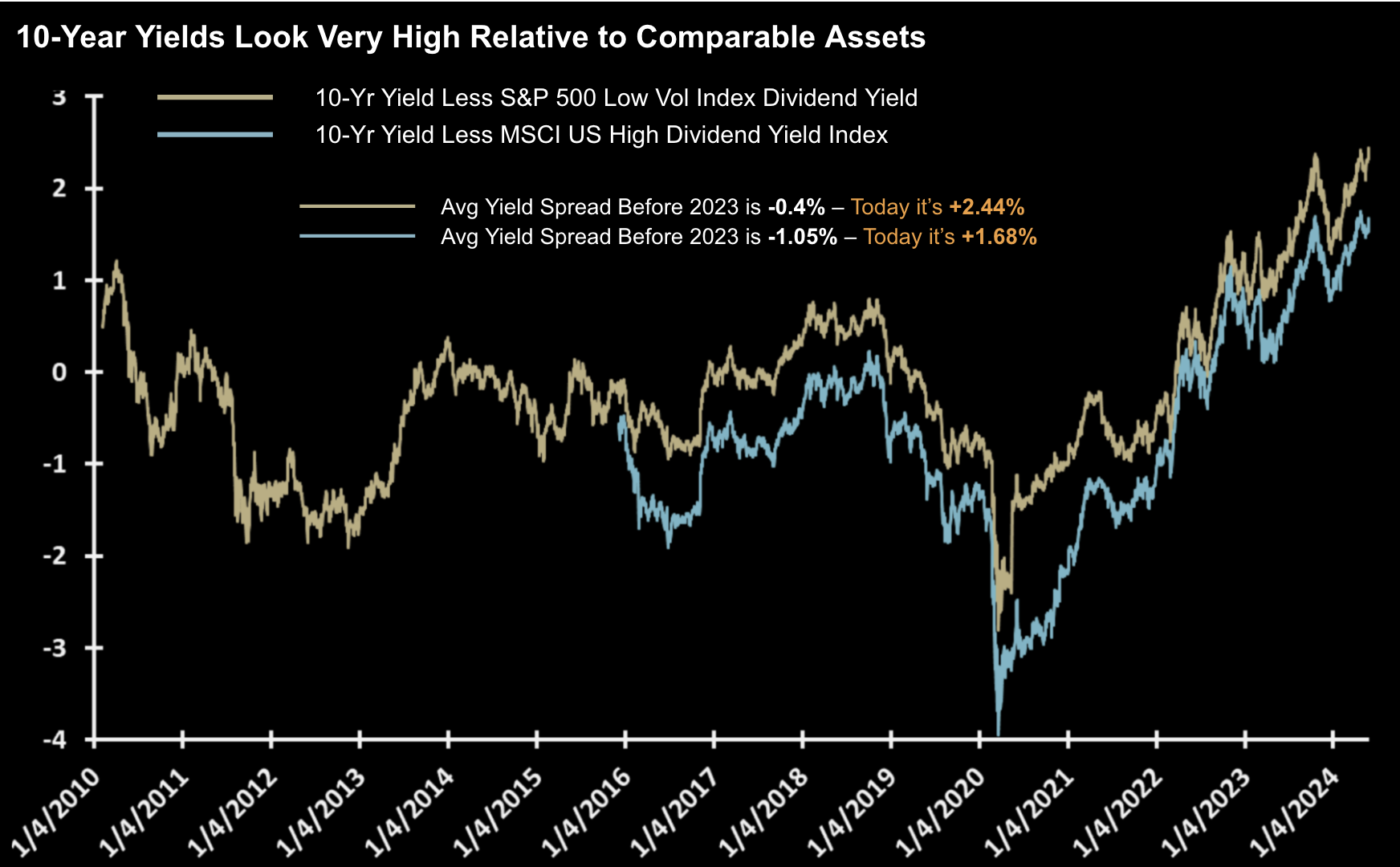

The chart below compares the difference in the (US) 10-year yield to the yield available on two popular substitute alternative investments: (1) the S&P Low Volatility Index; and (2) the MSCI U.S. High Dividend Yield Index”

Source: Jim Paulsen

Paulsen explains that investors typically buy a Treasury Bond for safety.

In that sense, an investment in a treasury bond is compared to very low risk equity investments (e.g., typically those which are low volatility and pay consistent dividends – perhaps a P&G, J&J or Coke)

As the chart above shows, the current 10-year bond yield at ~4.6% is much higher than what we have seen in the past.

For example, prior to 2023, these two equity dividend yields were typically “higher” than the 10-year Treasury yield.

Prior to 2023, the 10-year Treasury yield traded at a discount of -0.4% relative to the Low-Vol dividend yield but currently the Treasury yield is 2.44% higher.

Similarly, prior to 2023, the Treasury yield on average was -1.05% below the High-Div equity index yield, but currently it is +1.68% higher.

In short, something is out of whack.

And whilst we could write an entire post explaining why I think yields are trading at a significant premium (e.g. reckless government borrowing and spending) – for what it’s worth – using this comparison these yields seem too high.

But what’s very interesting (to me) is despite the 10-year pushing back up to 4.60% – equities continue to rally.

For example, if you had told me there would be a ~400 basis point move in the 10-year from August 2020 and equities would be at a record high – I would have laughed.

Putting it All Together

It’s impossible to know what lies ahead…

The further we extend our timeframes however – the greater the odds are in our favour.

That said, there will be no shortage of short-term forecasts.

However, when you don’t know the future – all we have are probabilities.

On this topic – one of the best books on understanding risk (and probability) is “Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk” – by Peter Bernstein

I was reading this book (again) during the week – and this passage came to mind.

For example, you could easily swap names like “Xerox” or “Polaroid” with something like “Nvidia” etc:

Consider a great growth company whose prospects are so brilliant that they seem to extend into infinity. Even under the absurd assumption that we could make an accurate forecast of a company’s earnings into infinity-we are lucky if we can make an accurate forecast of next quarter’s earnings – what is a share of stock in that company worth? An infinite amount?

There have been moments when real, live, hands-on professional investors have entertained dreams as wild as that moments when the laws of probability are forgotten.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, major institutional portfolio managers became so enamored with the idea of growth in general, and with the so-called “Nifty-Fifty” growth stocks in particular, that they were willing to pay any price at all for the privilege of owning shares in companies like Xerox, Coca-Cola, IBM, and Polaroid.

These investment managers defined the risk in the NiftyFifty, not as the risk of overpaying, but as the risk of not owning them: the growth prospects seemed so certain that the future level of earnings and dividends would, in God’s good time, always justify whatever price they paid.

They considered the risk of paying too much to be minuscule compared with the risk of buying shares, even at a low price, in companies like Union Carbide or General Motors, whose fortunes were uncertain because of their exposure to business cycles and competition.

This view reached such an extreme point that investors ended up by placing the same total market value on small companies like International Flavors and Fragrances, with sales of only $138 million, as they placed on a less glamorous business like U.S. Steel, with sales of $5 billion.

In December 1972, Polaroid was selling for 96 times its 1972 earnings, McDonald’s was selling for 80 times, and IFF was selling for 73 times; the Standard & Poor’s Index of 500 stocks was selling at an average of 19 times.

The dividend yields on the Nifty-Fifty averaged less than half the average yield on the 500 stocks in the S&P Index.

The proof of this particular pudding was surely in the eating, and a bitter mouthful it was.

The dazzling prospect of earnings rising up to the sky turned out to be worth a lot less than an infinite amount.

By 1976 (4 years later), the price of IFF had fallen 40% but the price of U.S. Steel had more than doubled.

Figuring dividends plus price change, the S&P 500 had surpassed its previous peak by the end of 1976, but the Nifty-Fifty did not surpass their 1972 bull- market peak until July 1980.

Even worse, an equally weighted portfolio of the Nifty-Fifty lagged the performance of the S&P 500 from 1976 to 1990.

But where is infinity in the world of investing?

Jeremy Siegel, a professor at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, has calculated the performance of the Nifty-Fifty in detail from the end of 1970 to the end of 1993.

The equally weighted portfolio of fifty stocks, even if purchased at its December 1972 peak, would have realized a total return by the end of 1993 that was less than one percentage point below the return on the S&P Index.

If the same stocks had been bought just two years earlier, in December 1970, the portfolio would have outperformed the S&P by a percentage point per year.

The negative gap between cost and market value at the bottom of the 1974 debacle would also have been smaller.

For truly patient individuals who felt most comfortable owning familiar, high-quality companies, most of whose products they encountered in their daily round of shopping, an investment in the Nifty-Fifty would have provided ample utility.

The utility of the portfolio would have been much smaller to a less patient investor who had no taste for a fifty-stock portfolio in which five stocks actually lost money over twenty-one years, twenty earned less than could have been earned by rolling over ninety-day Treasury bills, and only eleven outperformed the S&P 500.

Repeat: only 11 of the 50 outperformed the S&P 500 over the next two decades

It was funny, I heard some typical talking head on CNBC say this week “… you simply cannot afford to not own Nvidia here”.

I could only smile… where do they find these people?

Repeating the words of Bernstein:

“… these investment managers defined the risk in the NiftyFifty, not as the risk of overpaying, but as the risk of not owning them: the growth prospects seemed so certain that the future level of earnings and dividends would, in God’s good time, always justify whatever price they paid”

Hmm mmm.

Let us never overlook the laws of probability.

As I mentioned last week, I’ve been taking half positions in (boring) companies like (not limited to) “McDonalds, Starbucks, Bristol-Myers, AbbVie, Intel and J&J” of late.

Think of these like the “US Steel” in the 1970s – which went on to double in value within 4 years.

For clarity, I take a ‘half position’ at the current (attractive) valuation fully expecting the stocks to fall lower (e.g., maybe another 20-25%).

And if I’m fortunate enough that they do fall another 20%+ – it’s likely I will get settled into a full position for the next few years.

Again, the broader market (and specifically AI stocks) may continue to enjoy further upside from here.

That would not surprise me. Don’t bet against momentum.

In addition, the monthly chart tells me stocks are not over-extended relative to the past 20 years.

However, it’s not an area where I see attractive long-term risk reward.

Before I close, if you’re someone who is endlessly fascinated with the history of math, risk, probability and statistics – this is another great read.