Words: 2,735 Time: 11 Minutes

- Valuation concerns: experts see a forward PE of 25x for 2025

- Marks’ warns on risk – draws parallels to previous bubbles

- Conservative strategy – avoid the “lottery mentality” with investing

The other week, I shared the end of year 2025 targets from Wall Street experts…

Well, I have an update…

We can complement those targets with (EPS) estimates.

This is useful for two reasons:

It will allow us to determine if those targets will come from (a) earnings growth, or (b) multiple expansion.

Or perhaps a combination of both…

For example, 2024 was largely a story of multiple expansion (i.e., where investors are willing to pay a lot more for risk).

Stocks rose on higher multiples — a reflection of their optimism.

And while 2024 full-year results will probably show a ~12% year-over-year gain (almost entirely driven by tech)—the market doubled those returns (around 23% YoY).

That’s mostly multiple expansion.

Let’s update the 2025 end-of-year forecasts with EPS and forward P/E estimates

| Institution | 2025 | EPS | Fwd P/E |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oppenheimer | 7100 | 275 | 25.8 |

| Wells Fargo | 7007 | 274 | 25.6 |

| Deutsche Bank | 7000 | 282 | 24.8 |

| Soc. Gen | 6750 | 272 | 24.8 |

| BMO | 6700 | 275 | 24.4 |

| HSBC | 6700 | 268 | 25.0 |

| Bank of America | 6666 | 275 | 24.2 |

| ScotiaBank | 6650 | 255 | 26.1 |

| Barclays | 6600 | 271 | 24.4 |

| Evercore ISI | 6600 | 257 | 25.7 |

| Fundstrat | 6600 | 275 | 24.0 |

| Ned Davis Research | 6600 | 254 | 25.9 |

| RBC Capital Markets | 6600 | 271 | 24.3 |

| Citigroup | 6500 | 270 | 24.1 |

| Goldman Sachs | 6500 | 268 | 24.3 |

| JP Morgan | 6500 | 270 | 24.1 |

| Morgan Stanley | 6500 | 271 | 23.9 |

| UBS | 6400 | 257 | 24.9 |

| BNP Paribas | 6300 | 270 | 23.3 |

| Cantor Fitzgerald | 6000 | 267 | 22.5 |

| AVERAGE | 6617 | 268.0 | 24.6 |

As you can see, the average edged up from 6600 to 6617.

For all intensive purposes – the targets are ambitious.

However, the average forward P/E multiple next year—opposite a 6617 target—is ~25x.

And I thought 22x was rich?!

In any case, it’s clear overall sentiment remains extremely bullish.

I was going to use the word “positive” but that’s not strong enough.

For example, if the 2025 EOY target was ~6,100—sure—“positive” would be apt.

But north of 6,600?

However, what intrigues are the valuations.

Analysts are (mostly) convinced tech trees will grow to the sky; i.e., expectations of stronger growth despite already high (record) profit margins.

What could possibly go wrong?

The Importance of Margin of Safety

If I think about this blog’s goal – it’s to help you avoid losing capital.

That’s my primary goal.

And if you focus on quality companies – over time – the share price will take care of itself.

It’s an immutable law of the market.

But I always strive to do is first “look down” (i.e., what could I lose paying this price for the asset) versus “looking up” (i.e., what could I gain)

I can sleep far better at night feeling my chances of large losses are minimized.

And I think that should be the primary goal for any investor.

With respect to that objective – over the holiday’s – I re-read one of my favorite books on value investing by Seth Klarman.

“Margin of Safety: Risk-Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor”

The book is out of print and why it’s listed for $1,999.99 on Amazon.

It ranks among the best books on investing I’ve read.

In Chapter 6, Klarman discusses Ben Graham’s principle of a “margin of safety.”

From my perspective (and looking at the table above), this principle is lost on the majority of the investing public.

Klarman explains that value investing involves buying securities at a significant discount from their intrinsic value and holding them until the market recognizes their true worth.

Sounds simple right?

However, it’s not.

The essence of this approach is to buy “a dollar for fifty cents,” emphasizing patience and discipline.

What I’ve observed is most people lack both patience and disciline.

They are mostly impatient to make “fast money” – which means taking excessive risks.

Put another way – they spend most of their time “looking up” (e.g., if I can only make 20% gains this year etc etc)

It’s completely the wrong mindset.

For example, with the Index trading ~22x forward earnings, you’re not buying “a dollar for fifty cents”; you’re closer to buying a dollar for a dollar and fifty cents!

Klarman echoes Graham in stating that value investors are risk-averse.

They often go against market trends and endure long periods of underperformance when assets are overvalued.

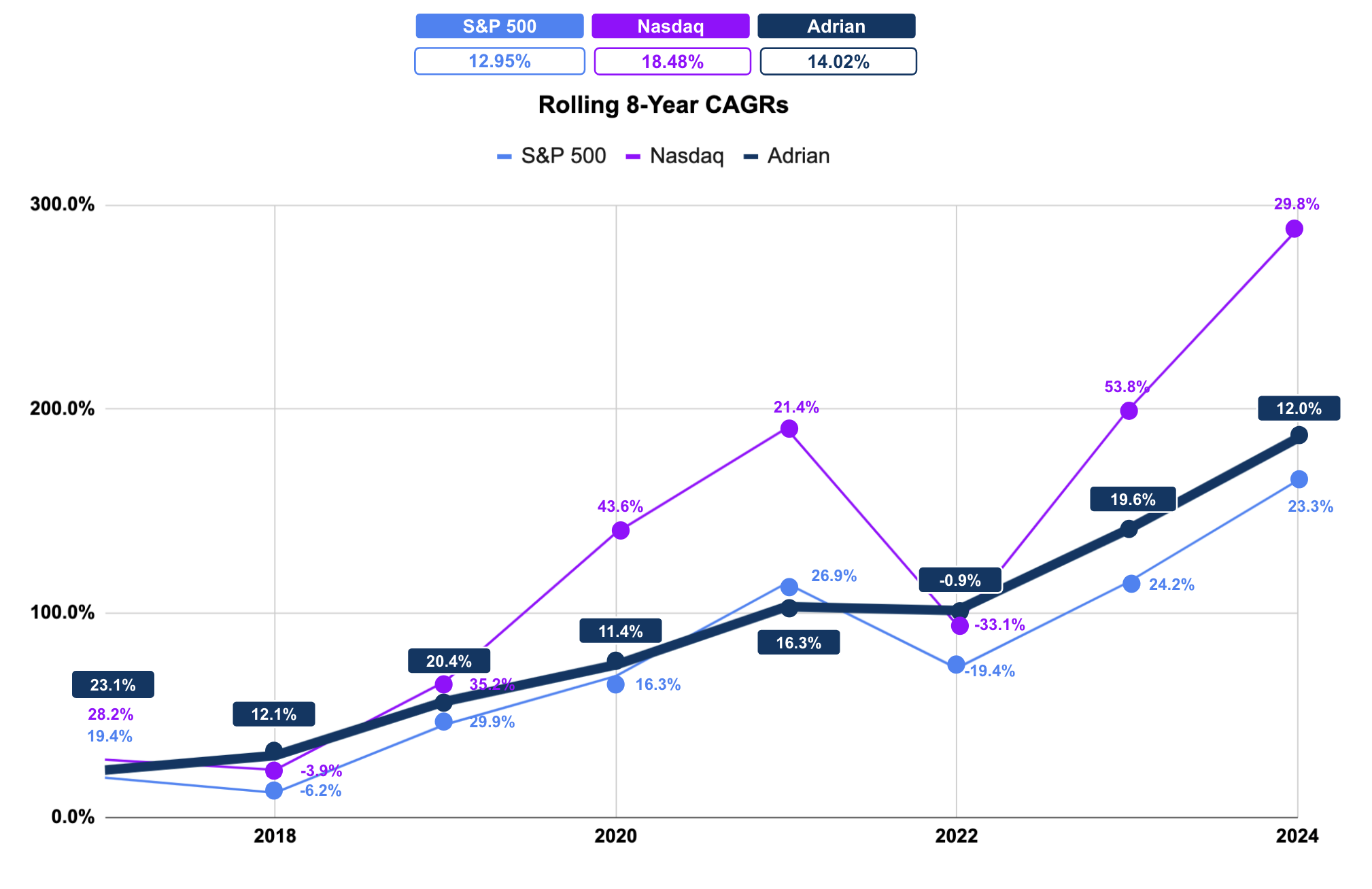

I can attest to that… you only need to review my performance the past 8 years (dark blue line):

The small labels are the annual returns for that specific year. The left axis is the cumulative return.

8-year CAGRs are provided at the top of the chart (e.g., S&P 500 at 12.95% and myself at 14.02%).

Now 2024 was another underperformance year for me (by about 11%).

As an aside, my largest position — Google (which is ~16% of my portfolio) had a solid year, returning ~30%.

That helped…

I justified maintaining the position given it trades at 22x forward earnings (and what I think offers the best value of the Magnificent Seven).

Needless to say – Google is of exceptional quality (e.g., in terms of its ROIC, EBIT, strong free cash flow, strength of balance sheet, competitive moat etc etc). It ticks every quality box I have.

Coming back to my 8-year rolling chart…

I want to highlight something very important: I’ve underperformed the S&P 500 for 5 of the past 8 years.

For example, in addition to the 11% underperformance over 2024 – we also find:

- 2023: I returned 19.6% vs S&P 500 24.2%.

- 2021: I returned on 16.3% vs S&P 500 26.9%

- 2020: I returned 11.4% vs S&P 500 16.3%

- 2019: I returned 20.4% vs S&P 500 at 29.9%.

In short, it’s not unusual for me to underperform when I believe valuations are extended.

Warren Buffett uses a baseball analogy to describe this level of patience, where value investors wait for the right investment opportunity—an undervalued asset they can understand and assess clearly.

Unlike institutional investors (i.e., those in the summary table earlier) who feel pressured to be fully invested, value investors only swing when they find a real bargain.

For example, if you are an intitutional investor – tasked with managing other people’s money – you MUST outperform the S&P 500 to justify your value (i.e., the fees you charge). Otherwise, your clients can enjoy the broad based returns of the Index for zero cost and effort (which is what I recommend most investors do)

On the other hand, I don’t feel the pressure to be “fully vested”.

What’s more, I never feel any pressure to outperform the S&P 500. All I need to do is return enough money (a return which is both sustainable and accetable) to live comfortably.

The S&P 500 for me is an arbitrary number.

For example, for most of this year I was about 65% invested (with no short positions). The balance in money markets and short-term bills (earning around 4.30% or so)

However, despite lagging the market significantly for 5 of 8 years, I’ve managed to avoid major downside.

That’s my goal.

My method is to seek very attractive risk/reward bets.

For example, with Google (and given its exceptional quality) – I think it deserves a multiple closer to 25x (not 22x). My entry price for the stock was around 18x (which I felt was good value – as I saw the downside risk to maybe 15x earnings based on its quality).

Put another way, I was risking 3x multiples lower in return for 7x multiples higher (in addition to expected revenue and earnings growth – which they have delivered in spades)

On the other hand, I found it difficult to justify 32x forward for Apple (which saw me sell the last of my shares two weeks ago at ~$254).

And whilst I don’t know if that will prove to be a good decision (it may not) – I can defend selling at a price of 32x given Apple’s profile.

On the other hand, I could not defend a decision to pay 32x.

For me, successful investing centers on discipline and process (whether you’re selling or buying)

It’s also maintaining rigorous standards and avoiding swinging at “bad pitches” (coming back to Buffett’s analogy). Buying Apple at 32x is taking a swing at a wild pitch.

Now if you can apply patience, discipline and rigorous process – you’re half a shot of having long-term success.

However, if you decide to swing at every pitch thrown (e.g., buying Nvidia or Apple at current prices) and you will strike out eventually. It’s just a matter of when.

Let’s explore this further…

How Do I Know What Something is Worth?

Knowing what something is truly worth is very difficult to determine—and often quite subjective.

For example, I asked myself this question of NVDA over the holidays.

I chose this stock for three reasons:

- Almost every analyst on the street has either a buy or strong buy rating (with no sell ratings) and a 12-month target of approximately $180.

- The stock is the poster child of the current AI craze; and

- At $140.14 per share, its market cap is $3.43T, representing a 6.4% weighting in the S&P 500.

To put this into perspective, only Apple is larger, with a $3.7T market cap and a 6.9% weighting in the index (at $242 per share).

When I applied a 5-year discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis to estimate its intrinsic value, my best guess was $85 per share for NVDA.

However, my valuation attempt assumed some very aggressive growth numbers, including:

- 40% revenue growth for five years beyond 2025

- 35% net income margins for five years beyond 2025

- A required discount rate of 10% (matching the index’s average long-term return), an

- A perpetual growth rate of 3.0% (required for estimating its terminal value)

Now think of how aggressive these assumptions are…

I am apply a consistent 40% growth rate in sales for the next 5 years (from an extremely high level).

And yet, even with these optimistic assumptions, I estimate its intrinsic value at $85.

This is a long way from price targets of $180–$220 (where some investors obviously expect far higher top-ling growth rates and margins)

The key takeaway is this:

Irrespective, what’s important is you do the work to understand the estimated intrinsic value of any stock you’re considering.

Remember – this is not an exact science. It’s impossible to estimate the true value of a business.

Heck – most people can’t even do it for a house – let alone a business for 5 or 10 years time!

Whether it’s Coca-Cola, American Express, Johnson & Johnson, or McDonald’s – the lesson is the same – you must determine if you’re getting a good deal.

And you can only do that if you have some approximately understanding of what cash that business is likely to generate over the next 5 (or 10) years.

Dealing With Uncertainty

The point I’m making is investing always involves uncertainty.

Further to my example above – you will never know all the factors that influence an investment.

What’s more, you won’t be able to ask all the right questions.

Again, consider the exercise I did with NVDA…

I had to assume specific revenue growth rates and net income margins projecting five years into the future.

What’s more, I need to assume a discount rate (where I applied 10%). If I was more conservative – I would apply something like 12% to allow for more things to go wrong.

But what’s the reality?

Anything could happen over five years—especially in tech!

Moreover, business values are not fixed, and stock prices often fluctuate due to a range of factors such as credit cycles, bond yields, and inflation.

Take today’s price action as a perfect example.

The U.S. 10-year yield surged above 4.70% on news of hotter than expected jobs data. The Nasdaq lost nearly 2% in response.

Now think of some of the questions this raises:

- What does a risk free 4.70% year do to equity risk premiums?

- What happens if the 10-year yield climbs to 5% or even 6%?

- And what would that do to DCF models?

In most cases, it would render them meaningless.

But let’s have some fun and imagine the 10-year yield returned to 3.0%.

Well, in that case, cheap credit would drive up valuations significantly.

This is what we saw during the bubble of 2021… ultra cheap money saw all risk assets soar in value (houses and stocks)

And of course what we need to think about inflation?

For example, will it return or will it trend lower? And from there, how will that impact interest rates and policy moves?

The point is there is lot of uncertainty!

Therefore, it’s near impossible to model anything with a high degree of accuracy (especially in rapidly changing areas like tech).

This is why I advocate a more conservative valuation approach, emphasizing worst-case scenarios.

Again – remember the goal is avoid losing a lot of money (“looking down”)

And the only way we will lose a lot of money is paying too much (that’s the risk)

For example, for NVDA, we would be wise to estimate intrinsic value assuming the 10-year is going to 5.0% — where growth rates are unlikely to exceed 50% every year for 5 years.

Looking down (not up).

Now in the event I get the numbers approximately right (including a healthy margin of safety) – the returns on my investments will take care of themselves over time.

Sure, the stock will most likely fall after I purchase it (as I like buying things when they are out of favor – as they are considerably cheaper) – but I’m okay looking wrong for a while.

More than fine.

Because I know that over time, quality metrics such as:

- strong (consistent) returns on invested capital (ROIC);

- repeated strong earnings before interest and tax (EBIT);

- steady strong free cash flows (FCF);

- returns on assets (ROA); and

- returns on equity (ROE)

.. will show up in the share price. But very rarely will that return be immediate.

Buffett calls it an immutable law of the market.

However, applying a margin of safety will help you reduce the risk of loss by allowing for mistakes, misjudgment, bad luck, and expected market volatility.

Howard Marks Warns of the Risks…

Marks is a value investor I follow.

He’s from the same school as Seth Klarman, Ben Graham, Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch, Joel Greenblat etc etc.

To start 2025 – he issued another timeless memo (read it here).

And if you don’t subscribe to Marks’ memos – you should.

Echoing what I’ve written (and especially in light of ultra bullish forecasts) – below are some of key points:

- Twenty-five years ago Marks published a memo titled “bubble.com”, addressing the irrational exuberance surrounding tech, internet, and e-commerce stocks during the late 1990s – which led to substantial investor losses.

- This history has made many investors wary of the possibility of new bubbles, particularly in the U.S. stock market, where companies like Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta, and Tesla—the “Magnificent Seven”—represent roughly a third of the S&P 500’s market capitalization (33.3% to be precise as of Jan 7th)..

- Marks asks the critical question: do such market concentration signal a bubble?

- Bubbles are often identified through valuation metrics, but he argues they are more accurately diagnosed through investor psychology

- He says a bubble is driven by irrational optimism and fear of missing out (FOMO), as investors buy assets based on belief in their inevitability, without considering downside risks (some of this should be sounding familiar!)

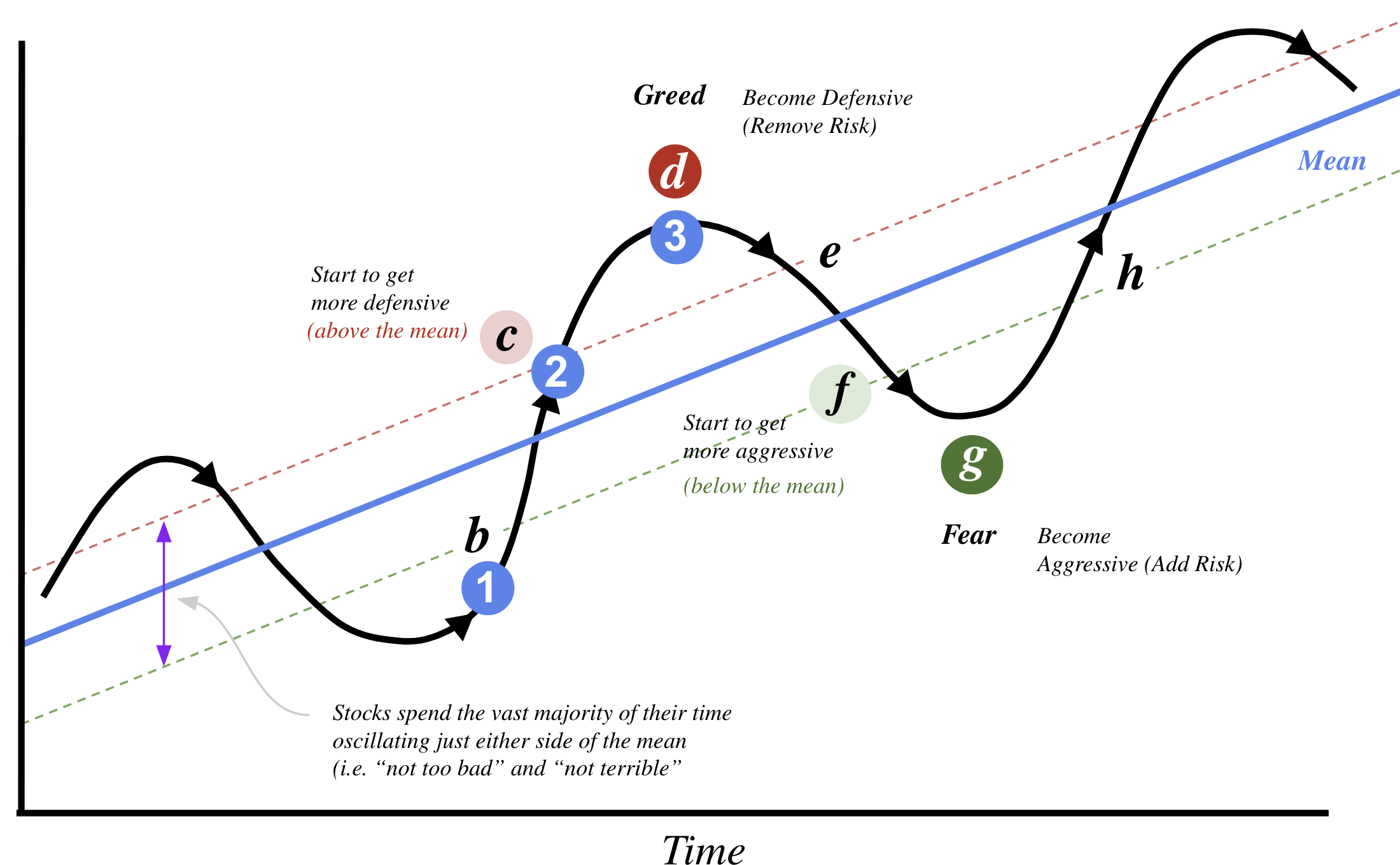

- Using Marks’ model – this type of behavior usually occurs during the third stage of a bull market—when optimism becomes detached from fundamentals, leading to speculative investments. I created this diagram to demonstrate Marks’ “third stage”

- He adds bubbles tend to emerge around new technologies, where there is little historical context to temper irrational enthusiasm. The dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, for example, was fueled by excessive valuations based on speculative metrics like “clicks” and “eyeballs,” despite the lack of real profitability. Marks also cites his experience with the “Nifty Fifty” stocks of the 1960s and 1970s, which were overvalued based on their growth potential

- Drawing on this – Marks feels this is not too dissimilar to the “lottery ticket mentality,” where investors expect extraordinary returns with little regard for the risks involved. In such an environment, valuations become decoupled from the underlying business fundamentals, with companies being priced on future profits they may never achieve. For example, tech companies like Nvidia may command high valuations, but the risks of competition and technological disruption remain significant. Note – this is interesting as I called out the same risks in my NVDA analysis “What Do You Pay for Growth?”

- Market behavior during bubbles tends to be marked by enthusiasm for new technologies spreading to other sectors. In the 1990s, for instance, a combination of low-interest rates and rapid growth in the tech sector created a euphoric market. However, rising stock prices often outpace underlying profits, signaling the possibility of an imminent downturn. And to that end, Marks draws a parallel to today.

- Marks’ urges caution, particularly regarding the high valuations of the S&P 500 (e.g., where “experts” are forecasting targets based on 25x multiples) and the speculative enthusiasm surrounding AI technologies

- In addition, he said don’t assume that the top companies of today will be the top companies of tomorrow. That’s rarely the case. And whilst Marks’ is the first to acknowledge that technological advancements (such as AI etc) will drive market growth and greater productivity — they also carry inherent risks. And that risk is what you pay.

Putting it All Together…

It would not surprise me to see 2025 repeat the drawdowns we saw in 2022.

And we could see 10-15% lower in the first half.

For example, longer-term readers will recall that during Q4 2021 – I warned of excessive valuations (specifically in tech).

But conditions are a little different this time – especially with rates.

10-year yields are now above 4.70%

And should they continue their march towards 5.0% – valuations (and earnings) will be challenged.

Now the “experts” are assuming significant earnings growth for next year (evidenced by the EOY 2025 target and EPS estimates)

We will see how that turns out…

Marks’ “lottery ticket mentality” analogy is a good one; i.e., where the majority of investors naively expect extraordinary returns with little regard for downside risks.

They say there are only two certainties in life: death and taxes

However, is there nothing more certain than waves of irrational self-defeating behaviors in the stock market (e.g., fear and greed being two)?

Before I close, consider the tale of two fictitious investors.

The “aggressive investor” is on the left; and the returns of the “defensive investor” on the right. Both investors start with $1,000

| Aggressive Investor | Defensive Investor | |||

| Year 1 | 17.0% | $1,170 | 9.0% | $1,090 |

| Year 2 | 26.0% | $1,474.20 | 18.0% | $1,286.20 |

| Year 3 | -22.0% | $1,149.876 | 4.0% | $1,337.65 |

| Year 4 | 25.0% | $1,437.35 | 16.0% | $1,551.67 |

| Year 5 | 21.0% | $1,739.19 | 12.0% | $1,737.87 |

| Year 6 | -8.0% | $1,600.05 | 2.0% | $1,772.63 |

| CAGR | 9.86% | CAGR | 12.13% | |

In this example, the aggressive investor saw returns as high as 26% – combined with drawdowns as low as 22%.

Sound familiar?

The defensive investor on the other hand shows a very different profile. Where returns were as high 18% (their best year) and as low 2.0%. There are now aggressive drawdowns.

Despite the aggressive investor handily outpacing the defensive investor for 4 of the 6 years by ~10%… the defensive investor wins comfortably.

The 6-year CAGR difference between two is meaningful – due to the defensive investor not suffering large drawdowns.

For example, if this was you in 2022 (where your portfolio was hammered by over 20%) – don’t leave yourself open to the possibility of repeating it in 2025. You will hand back the gains of 2023 and 2024.

The time to be more aggressive will be when valuations are far favorable.

We are a long way from that.

Something to think about….