Words: 3,668 Time: 15 Minutes

- My preferred quality financial metrics and why

- Using EV/EBIT and P/FCF as a way to determine value

- With valuations exceptionally high – your focus should be on lasting value

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth”

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

My last post talked about “Inverting Your (Investing) Mindset”.

It was written to help you avoid making large costly mistakes.

Charlie Munger once joked “all I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll never go there.”

Jokes aside – it’s the same approach you should apply with investing.

And it’s not difficult to do….

The math – for example – is very simple. It’s addition, subtraction, division and multiplication. If you have access to a calculator – you’re all set.

The challenge is mastering your emotions (and any self-defeating behaviors).

A calculator (or AI) can’t help you with that.

From mine, this game is more EQ than it is IQ.

Think of it as a test of your character versus your intellect (read this post).

For example, many highly intelligent people get investing wrong (e.g., due to emotions such as greed, fear or some inherent bias)

This post talks about how we can simplify our approach to avoid taking excessive risks.

For example, I will talk to how I identify:

- Higher quality businesses (e.g., the specific metrics we should evaluate); and

- Two methods for determining value (neither of which are price-to-earnings multiples)

To set the scene, I calculate 26 metrics for every S&P 500 company (every quarter and year). These metrics fall into three categories:

- Valuation (7 metrics);

- Growth, Profitability and Effectiveness (10 metrics); and

- Capital Structure and Debt, Interest Coverage and Liquidity (9 metrics)

What’s more, I do this on a rolling 10-year basis.

That means analyzing every balance sheet, income statement and cash flow statement for all 500 companies going back 10 years.

And that’s how I determine a high quality company and what it’s potentially worth (which I will expand on below).

Let’s take a look…

Simplifying Things

When faced with a matrix of 13,000 data points (i.e., 500 companies x 26) – you need a system which removes complexity.

With the click of my mouse – I can quickly see the stocks which appear to be of very high quality and/or warrant further investigation.

For example, they have a consistent record of strong free cash flows, very high profit margins and capital structures which use very little debt.

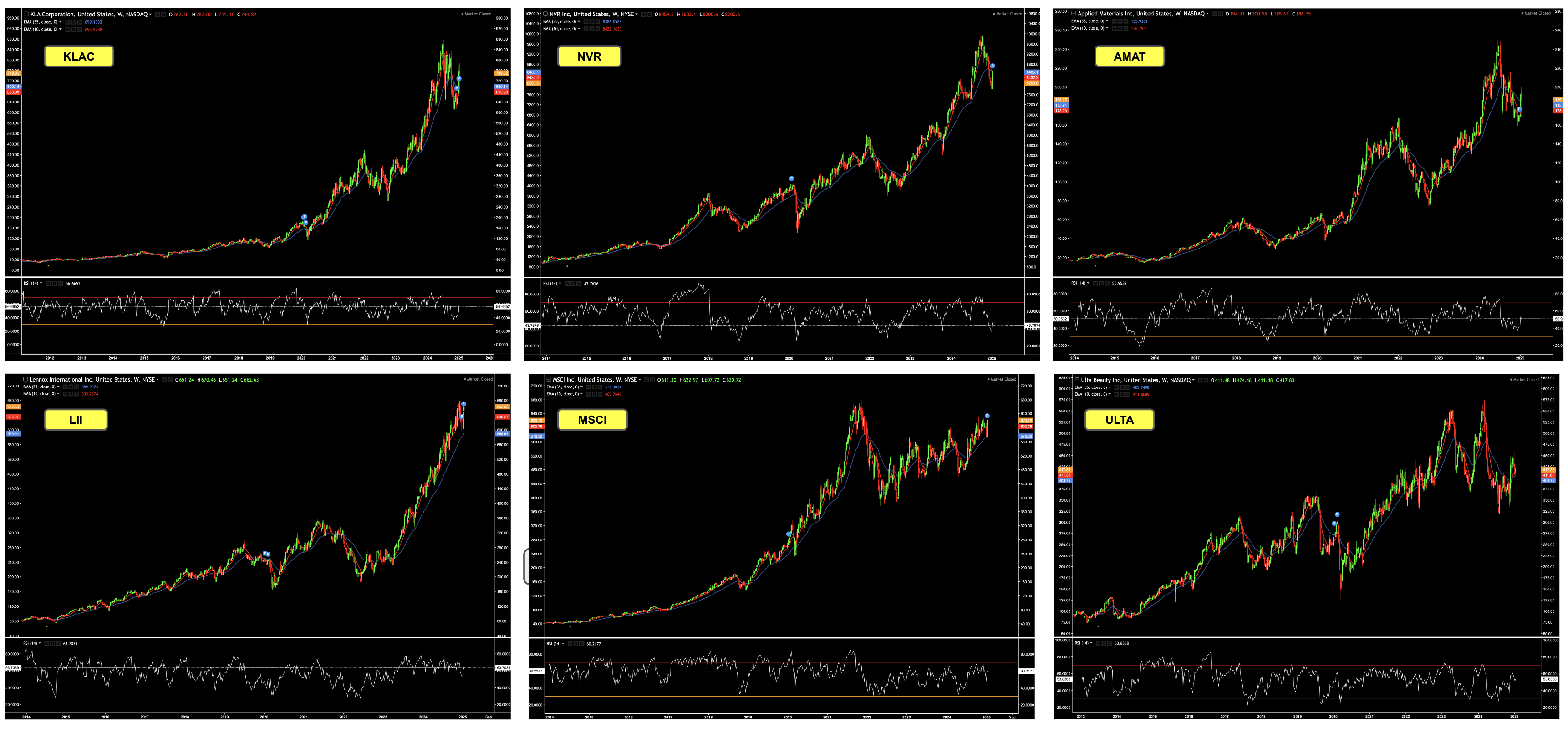

Beyond the Mag 7 (which tends to attract most investors at almost any price) – below are few names you may be less familiar with:

- KLA Corporation (KLAC)

- NVR Inc (NVR)

- Applied Materials (AMAT)

- Lennox International (LII)

- MSCI (MSCI)

- Ulta Beauty (ULTA)

- Paycom (PAYC)

- Arista Networks (ANET)

With respect to 2 of the 10 “growth, profitability and effectiveness” metrics I track – each of these names exhibit:

- 10-year Free Cash Flow (FCF) CAGRs above 15%; and

- 10-year avg Return on Invested (ROIC) above 30%

By any measure – these are impressive numbers. To give this greater perspective – consider that for every S&P 500 company:

- 87 of 500 (~17%) satisfy FCF CAGR of 15%+ over 10 years; and

- 52 of 500 (~10%) achieved an ROIC of 30%+ over the same period

- It’s not just “Mag 7” where there has been significant share price appreciation; and more importantly

- When a business has this level of consistent FCF and ROIC (w/solid profit margins) – the share price will appreciate.

It’s an immutable law of the market.

But here’s something else…. consider the inverse of these findings:

- ~80% of S&P 500 companies generate less than a 15% FCF CAGR over the past 10 years; and

- ~90% of S&P 500 companies generate less than an average 30% ROIC over 10 years.

That’s helpful – as it allows me to focus my investable capital.

Therefore, I can reduce the odds of making a poorer choice (and/or costly mistake).

For example, what if I blindly bought a stock which was consistently burning cash?

Or had never shown an ROIC greater than say 15%?

But instead all I saw was the stock going up – where some talking head on CNBC or Twitter said “… you have to be in this stock”?

Now that’s not to say “cash furnaces” may not succeed over time… some of them will.

However, you’re taking a larger risk in terms of getting it wrong. That’s the important piece.

Therefore, you’re able to adequately gauge the relative level of capital to give these opportunities.

For example, rather than “5.0%” of your total capital – allocate these stocks maybe 0.50%

If they have happen to make money in time – maybe it goes up 10,000%+

But in the likely event it remains a cash furnace – you’ve only lost a small fraction of your capital.

In any case, finding high quality business with consistent track records is easy if you do the work.

Finding quality essentially focuses on the strengths and weaknesses of the business.

This is an important differentiation…

For example, I’m not asking whether the company can rapidly “increase sales” or “earnings” over the next few quarters.

No…

What I’m more interested in is whether it demonstrates a sustainable competitive advantage over the next five plus years.

That’s much harder to do.

In short, you should be able to articulate three to four strengths and weaknesses of the business you plan to own.

If you can’t do that – then challenge yourself on why you are buying it.

And it doesn’t need to be any more complicated.

For example, if you start introducing additional layers of complexity (e.g., why it will turn things around; or why it will revolutionize or disrupt some market) — you introduce additional risk.

In general, it’s easier to make money through simple investment ideas.

Warren Buffet once said “I would much rather step over 1-foot bars and than try and clear 7-foot hurdles”

Makes sense to me.

Now finding quality companies isn’t terribly hard (if you’re willing to look)

However, finding great businesses offering compelling value can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

Let’s drill down on the concept of value…

The Meaning of Value

- Shows consistent strong revenue growth;

- Boasts impressive free cash flow and return on invested capital;

- Double digit returns on assets and equity;

- Does so with defensible strong net profit margins (i.e., pricing power);

- Does not use excessive leverage; and

- Can meet any short-term interest obligations from existing operating cash flow etc

Great!!

But what is it worth? And what method do you apply to determine if its value (or excessively priced)?

As I’ve written in the past – there are any number of methods you can use to evaluate what a company is worth.

For example, a popular method is using a discounted cash flow (DCF)

Here’s a free .xls template I developed using https://tradethetape.com.au/nvda-what-do-you-pay-for-growth/ as an example.

However, as I highlighted, using a DCF method requires making a lot of assumptions. For example, these include:

- Cash Flow Projections: Relies on accurate cash flow projections based on future performance assumptions;

- Constant Discount Rate: Assumes a relatively stable and suitable discount rate over the projection period;

- Terminal Value: Incorporates a terminal value representing cash flows beyond the explicit projection period;

- Stable Financial Leverage: Expects unchanged capital structure, ensuring consistent risk profile and discount rate throughout the projection period.

Many analysts will look to project cash flows over 10 years.

I think it’s impossible to forecast what conditions will be in 10 years – especially for highly disruptive sectors like tech.

What’s more, this says nothing about what interest rates will be or rates of inflation etc etc.

However, if this business was a utility stock (i.e., largely stable and predictable with its earnings) – sure – DCF will get you in the ballpark.

But in general – the longer you forecast using DCF – the greater the inaccuracy.

My preference for establishing value is two fold:

- EV/EBIT (enterprise value/earnings before interest and taxes); and

- P/FCF (price to free cash flow)

#1. EV/EBIT

EV/EBIT is one of the 7 valuation metrics I track.

I like using EV/EBIT because it introduces the balance sheet to the multiples.

The main goal of the analysis is to find out approximately how much the business is worth, in a reasonable range.

Again, it’s important here that I’m not interested in calculating its value to a “decimal point” (that’s impossible).

In short, I’m looking to be approximately right (and not precisely wrong).

By using Enterprise Value (EV) – I’m including both cash and debt in the calculation, which is far better than just looking at market capitalization.

With respect to Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) – my goal is to see how much interest the company is paying.

However, as a very conservative investor (focused on not losing capital) – I prefer companies with very little to no debt.

Therefore, I expect very low interest expenses.

In addition, tax is also a concern – because if a company pays a lower tax rate than its peers – you should try and understand why.

For example, if there is no valid reason for a lower tax rate, then it’s a red flag. They are either:

- Cheating the tax authorities; or more likely

- Overstating its profits or earnings

By way of example, if I look at KLAC (one of the eight example companies I outlined earlier) – its EV/EBIT is 26.5x (up from 18.0x at the end of 2023).

This is because it has enjoyed significant price appreciation.

On the surface, a value of 26.5x is exceptionally high.

However, the value should be viewed in light of its industry, growth prospects, and the overall environment.

Given this is in the semiconductor space – I understand why it has appreciated so much. There is a lot of hype around what (AI) chips will be required.

However, from mine, a value of 18x is a fairer price

To give you a rough idea – below are average EV/EBIT ranges for the following 4 sectors:

- Tech/Software: 20x to 50x

- Consumer Discretionary: 15x to 30x

- Industrials: 10x to 20x

- Utilities: 8x to 15x

KLAC belongs to the first category (tech). Therefore, I would think something at or below 18x is reasonable.

But let’s break these down further (to see if the asking price of 26.5x EV/EBIT is “excellent value” – as that is the only reason we would take the risk of ownership)

Growth Potential:

- It has been growing its revenue at a 13.6% CAGR for the past 10 years – solid but in the lower range;

- This year (TTM) growth is expected to be flat – therefore this tells me the valuation feels rich;

- This is consistent with what we’re seeing in the semi industry (where much of the near-term growth has been pulled forward)

Profit Margins and Competitive Advantage:

- Its net profit margin average over 10 years is 26% – very strong

- This year it is expected to be 29%

- It tells me they enjoy a strong competitive advantage in the industry

Market Conditions:

- We’re in one of the greatest bull markets in history – with the Index averaging a CAGR of ~11% since 2008.

- Therefore, investors are paying a premium for stocks. This helps explain a lot of the 26.5x EV/EBIT multiple (i.e., FOMO)

Comparison to Historical Average:

- Its current EV/EBIT ratio of ~26x is significantly higher than previous years.

- For example, 2018 – 10x; 2019 – 15x; 2020 – 19x; 2021- 20x; 2022 – 14x; and 2023 – 18x (average 16x)

- Therefore, you could argue it’s trading ~60% higher than it’s 5+ year average

In summary – this stock is not offering investors great value. It’s expensive.

And it exemplifies a stock which is of very high quality – however it has run too far.

Let’s now turn to the second method of valuation – using free cash flow.

#2. P/FCF

Unlike EV/EBIT – using Price to Free-Cash-Flow (P/FCF) provides me with insight into how much investors are willing to pay for each dollar of FCF generated by the company.

We define this ratio as the company’s market capitalization (i.e. determined by its price x share issued) divided by its FCF — that is, the cash flow available for distribution to stakeholders.

Again, the math is straight forward.

Found in the company’s cash flow statement, FCF is operating cash flow minus capital expenditures.

Again, let’s take another look at KLAC.

Today, its P/FCF is 36.8x

If we invert 36.8x – we get its P/FCF yield – a figure of 2.7%

For me, I like to buy high-quality (growth) businesses with FCF multiples of less than 15-17x (or an FCF yield of ~6.7%).

Again this will vary depending on the industry which the business operates.

Now 6.7% is a very decent FCF yield.

Clearly I think KLAC is overpriced on this metric (i.e., yielding only 2.7% based on its FCF).

However, I will also look at the sensitivity and any assumptions made to establish a comfortable multiple.

What does that mean?

If we assume the business is of high quality (which we demonstrated earlier) — and likely to continue growing the top line by double digits – then up to 17x is fair.

You’re paying a fair price for a very good business.

However, 36.8x is not a fair price.

If I owned the stock (and I do not) – I would be happy selling it here.

Straight Forward Methods

What I’ve shared are very simple, straight forward methods.

The math (and process) required are not difficult.

And furnished with years of balance sheets, cash flow statements and income statements – you can calculate the financial ratios.

But…

What it requires is a level of prudence to come up with a reasonable estimate of the long-term figures.

For example, if looking at applying a P/FCF valuation – assigning a fair value of say “15x to 17x” for KLAC requires some judgement.

Is this a growing company? What is fair for that industry? What’s the outlook? What are the historical averages etc?

Judgement is harder to do… as there is no “set rule” as to whether “17x” is considered ‘deep value’.

For example, let’s say KLAC was a cyclical business – I would probably look for a value of closer to 13x etc.

Now you might think that number should be “20x” or higher for this kind of business?

That’s your call. However, the higher you go – the greater the risk.

With respect to the quality side of the equation – I also choose to set a high bar.

Yes, it reduces the pool of ideas, however my goal is to eliminate lower quality (or higher risk) businesses.

For example, if we think about the metric of strong consistent ROIC – it provides me with:

- The return generated on capital specifically invested by equity and debt holders after subtracting non-operating liabilities (e.g., cash, short-term investments).

- Focuses on how efficiently the company uses the funds actively invested in generating its core business profits; and third=

- Gives valuable insight into whether the company is generating value above its cost of capital (WACC).

In other words, I want to see how efficient and profitable a business is on its investments.

Again, here I will turn to Buffett about the goal of investing:

“The primary test of managerial economic performance is the achievement of a high earnings rate on equity capital employed (without undue leverage, accounting gimmickry, etc.) and not the achievement of consistent gains in earnings per share”.

Note the latter part of his sentence… it is not the achievement of consistent gains in earnings per share.

The question of how well a company is deploying its capital (and the returns it generates on that capital) strikes at the very heart of this endeavor.

Some Words on Allocation

Knowing we cannot know what will happen, we need to factor this into how we allocate our capital.

Therefore, I think sufficient diversification is your best defense.

I have never been one to heavily concentrate my investment portfolio. Again, it only increases your chance of failure.

For example, last year, my largest concentration was in Google.

It was as high as 16% of my total portfolio (a slightly uncomfortable level).

Two reasons:

- Quality: very strong record of high FCF, ROIC, ROE and ROA; and

- Valuation: its EV/EBIT is 23x (not cheap but not excessively priced)

For example, if its EV/EBIT was closer to 30x – I would have sold the entire position (as I did with Apple a few weeks ago)

But to maintain a 16% total portfolio weighting – I periodically sold small amounts as the price went higher (where its gains were ~30% last year)

Overall, my portfolio is not too concentrated.

However I do think concentration can also be more of a bull market phenomenon.

For example, in a bear market, if you are too concentrated, you are extremely vulnerable to the downside.

And if things were to turn south – I would not hesitate to reduce this concentration in any one stock to less than 10%.

Overall, my approach is always to diversify my ideas.

That said, I’m not of the mind you should diversify the portfolio to the extent of creating a quasi-market index (e.g., owning more than 30 stocks)

For me, a number between 10 and 20 stocks feels about right.

In short, there are not that many well priced (high quality) stocks available.

But if you are buying 30+ stocks – I would say you are better off simply buying the Index and not doing all the work (which is what I recommend for 90% of all investors)

With respect to my average time horizon – it’s between four to five years on average (sometimes longer)

I choose this time horizon as I’m generally buying something which is out of favor (and why it’s a discount) – and it will take that long for the market to recognize its qualities (e.g., above average FCF, ROIC, ROA, ROE etc).

It’s like buying a warm winter coat in the middle of summer – they are generally on sale. However, by the time winter rolls around, the coat is worth more.

Same thing.

In fact, one of the ways I find value with my spreadsheet (which captures valuation and quality metrics in real-time) – is it also highlights 52-week lows.

For example, let’s say I see a stock down “30%+” or more (there’s no set number) – it’s a signal to revisit its quality.

What are its free cash flow yields? Its return on invested capital? Its weighted cost of capital? Its return on assets and equity? It’s debt levels and so on?

Most of the time there’s a very good reason it’s trading lower — but occasionally it’s simply the market discarding something of quality.

And that’s when I get excited…

Putting it All Together

This gives you some insight into how I go about things…

Given the tsunami of news and information hitting the tape today – separating noise from signal has never been more important.

Your focus should remain fixed on what is of lasting value.

Again, the math is straight forward – but it requires a little work.

I’ve written my own program which dynamically pulls:

- Past 10 years balance sheets, income statements and cash flow statements for every stock;

- Calculates 26 valuation and quality metrics (in real time);

- Shows me the price performance for every stock over 1 month, 1 quarter, 1 year, 5 years and 10 years (in real-time);

- Applies a weighted score to each stock based on industry standards and certain criteria I prioritize.

From my there, my constructed portfolio has its own average FCF, ROIC, ROA, ROE, D/E ratio etc.

I’m then able to compare that to the market average as a whole.

However, you don’t need to write code like I have done.

There are lots of online services available to provide this information (typically b/w US$500 (e.g. Gurufocus, Finbox) and US$2,000 per year)

To pull the raw data – I subscribe to WiseSheets API for US$60 per year.

You key in any ticker (globally) and it will pull its balance sheets, income statements and cash flow statements.

From there, I have scripted several spreadsheets to calculate the ratios and financial summaries.

Structuring this across growth, profitability, efficiency and capital structure / debt / liquidity metrics allows me to gain:

- A good understanding of the business’s historical trends (and consistency); and second

- To compare capital returns among different businesses / industries.

By way of example only, if I simply look at the metric ROIC – in minutes I’m able to see

- ~10% of all S&P 500 companies averaged an ROIC 30%+ for the past 10-years;

- ~21% or 107 companies averaged an ROIC of 20.0%+

- ~32% or 161 companies averaged an ROIC of 15%+

Based on only this metric – I can focus my efforts on the top 32% of companies (where anything over 15% for 10+years is excellent).

And from there, I expand my criteria.

For example, even if the ROIC has averaged 20%+ for the past 10 years – it can still be a trap if the business does not have pricing power.

Therefore, I will add a net profit margin filter to the group of ~21% of high ROIC stocks.

This will tell me if they are being squeezed by competition or inflation.

For example, here I can see the entire market averages a net profit margin of ~12% (i.e., Net Income / Total Revenue)

Now just ~19% (97 companies) of all listed S&P 500 companies boast a 10-year average Net Profit Margin of 20% or greater.

And this process continues as I work my way towards valuation (e.g., EV/EBIT and P/FCF)

I would highly encourage you to develop a system for determining:

- (a) companies of high quality; and from there

- (b) establish what represents value.

I don’t pretend to have found some “investing panacea” – as there are a plethora of methods – but these work very well for me.

What’s more, I’m leveraging the methods of those who have already figured this out (e.g. Warren Buffett)

They’re simple and effective.

For example, I’ve backtested my quality and valuation criteria over 20 years (from 2001).

The CAGRs for stocks which meet my criteria – if held over 4 years – consistently outperform the Index by several percent (and in some years – by much more).

But for me what is more valuable is the downside protection.

Rarely do stocks which meet these criteria ‘blow up’ (e.g., drop more than say 30% over the 4 years).

In short, they generate far too much cash on their capital (with very low levels of debt)

The risk is always what you pay.

In other words, you can still lose a lot of money “buying Apple at $254” (as I highlighted recently)

However, if you apply stringent criteria of valuation multiples such as EV/EBIT or P/FCF (or one that suits your criteria) – your downside risk is limited.

I hope this was helpful….