- US 10-Year races towards 5.0%

- Why credit / debt investment deserves a place in your portfolio

- A look at Howard Marks latest memo

Let’s start with some good news…

First, inflation is slowly but surely coming down.

Exclusive of shelter costs – which remains stubborn – inflation is gradually trending towards the Fed’s 2.0% target.

All going well – we might see it with core by the end of 2025 (at a guess)

Second, most people have jobs and are enjoying ~4% wage growth.

That’s good news as it means the economy remains on solid footing.

Recessions are unlikely if people are not losing jobs.

And as we saw with the latest September print for retail sales – never understimate the US consumer’s desire to keep spending.

September retail sales grew from the prior month, reflecting continued resilience in the American consumer despite predictions of a slowdown.

Retail sales rose 0.7% in September from the previous month, more than double Wall Street’s estimates for 0.3% growth.

Sales excluding auto and gas increased 0.6%, above estimates for a 0.1% increase compiled by Bloomberg. Meanwhile, August’s sales were revised up to 0.8% from a previously reported 0.6% increase

What do you mean they don’t have the money… they have credit!

Okay – that’s all good – what’s the bad news?

Interest rates are likely headed higher as a result.

What’s more, investors need to brace for a lengthy period of higher rates for longer.

Years.

The days of “free money” are long gone.

And that has meaningful implications on how you allocate your capital in the years ahead.

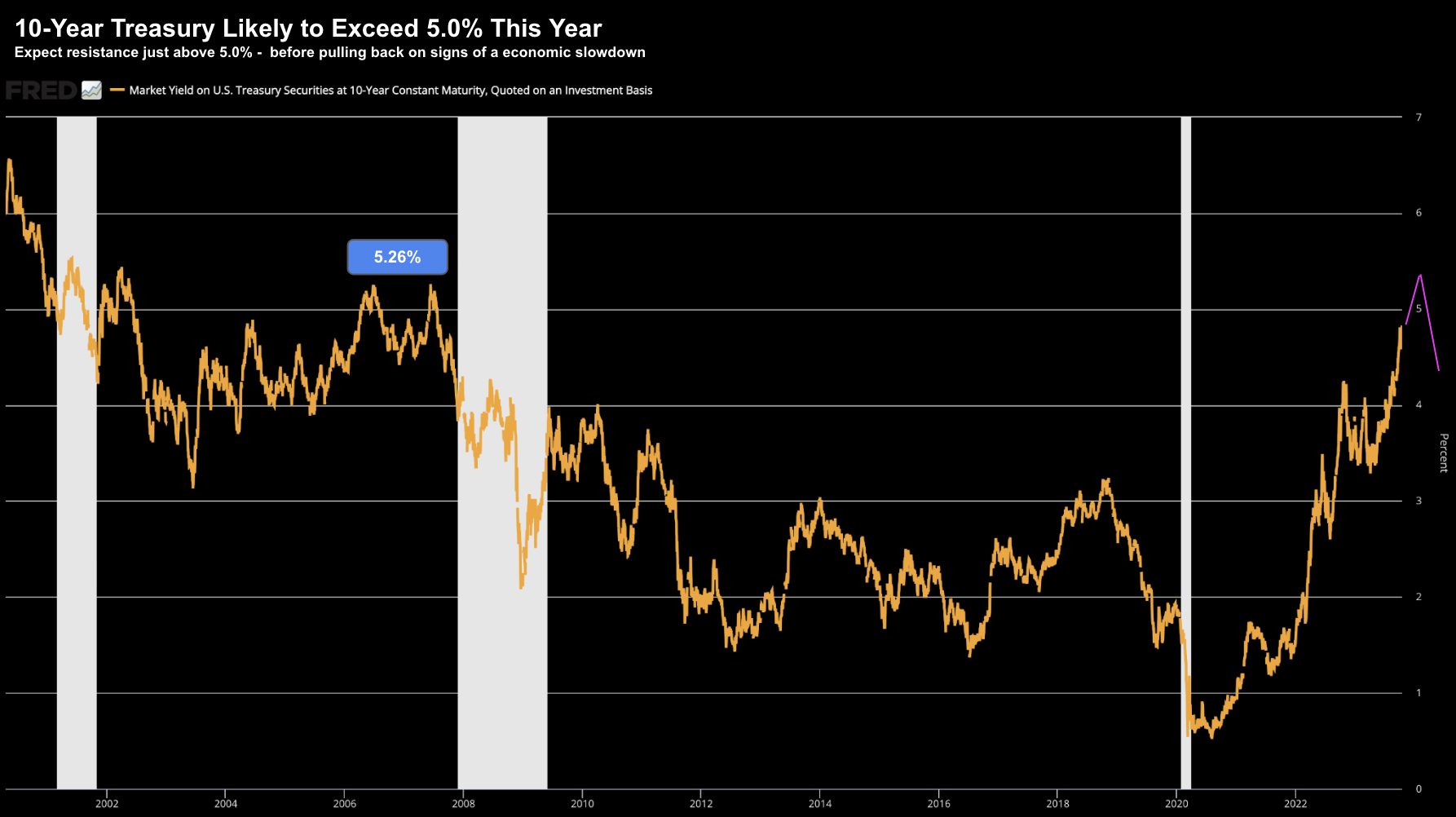

US 10-Year to Break 5.0%

Since Janet Yellen announced the torrent of debt to be financed July 31 this year (one third more than what the market expected) – we’ve watched the bond market recalibrate.

Yields leapt higher putting a lid on the equity rally.

The S&P 500 highs for 2023 were in.

Consider the all-important US 10-year yield…

Today it surged above 4.91% – a level not seen since 2007.

5.0% appears to be a matter of time…

And whilst a level of 5.0% is not historically high (it’s about average) – it’s the speed at which we got here which is troubling.

This is the bond market telling investors what to expect.

Two forces are giving yields a (meaningfully) higher ‘floor’

- Record pubic deficits and debts – as investors demand a reasonable (longer-term) risk premium; and

- Very strong economic growth continuing (e.g., supported by perceived robust jobs and retail sales)

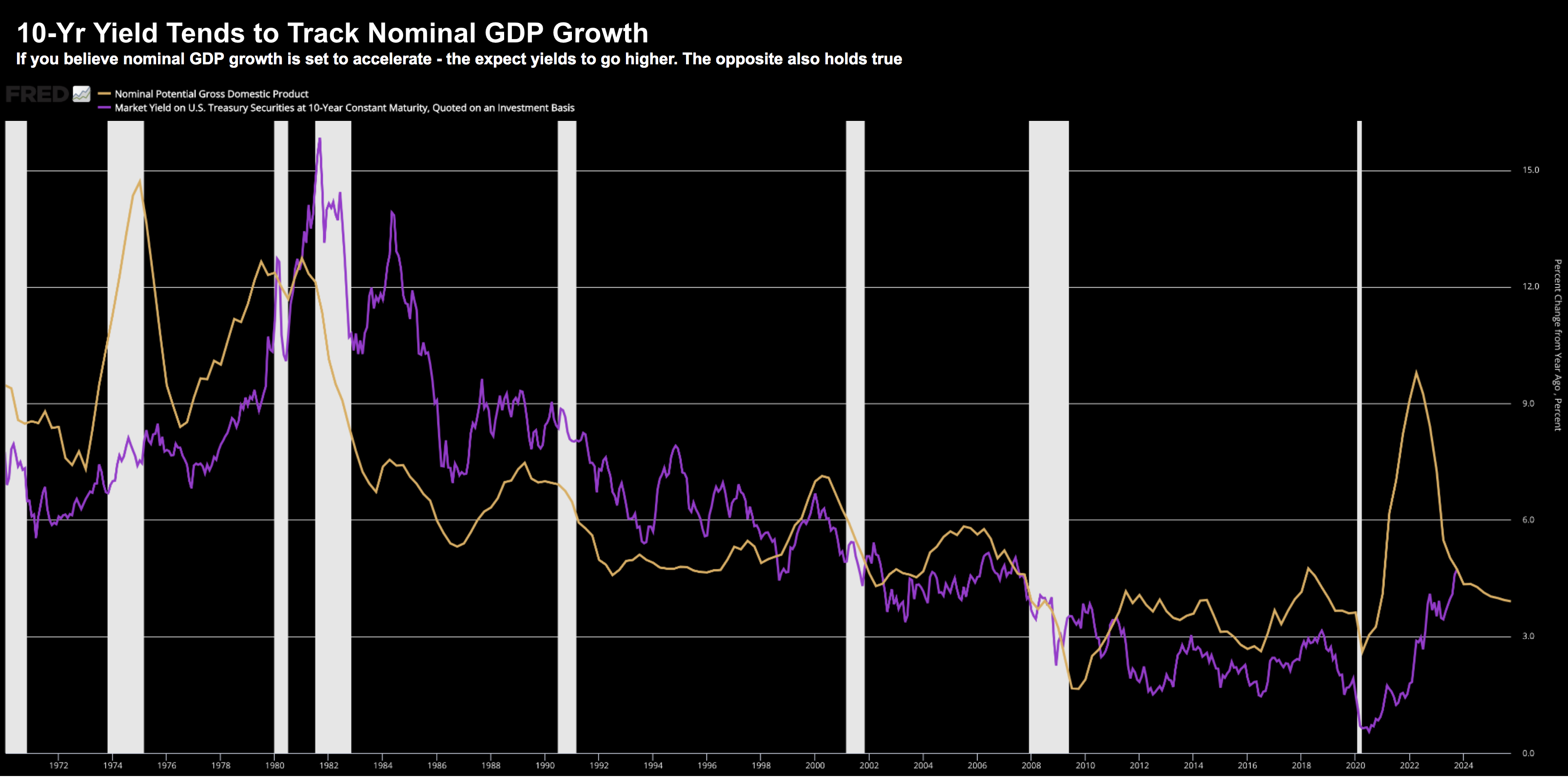

Below is the long-term correlation between the 10-year yield and nominal GDP growth

Arguably there’s a third – the market assumes that geopolitical risks remain very low.

The final one seems somewhat out of place given what we see with (certainly not limited to):

- China / Taiwan

- Russia / Ukraine

- Israel / Hamas

For example, if the market felt geopolitical risks were high – you might expect a rush into safe haven assets (like US Treasuries) – driving down yields.

This clearly hasn’t been the case.

We will see how this works out….

Again, these are assumptions the market is making (right or wrong)

But let’s talk more to this “new normal”…

As I say, the script for the past 20+ years has been a recipe of artificially low rates (helped by emergency measures such as QE) – sending all risk assets meaningfully higher.

Investors were highly incentivized to take greater risks – given the ultra-low cost of funding / low returns on fixed income.

But is that the investing script for the next decade?

I don’t think so… and neither does Howard Marks.

Rethinking Your Investment Strategy

Last week we were treated to another thought provoking memo from Howard Marks.

Apart from Warren Buffett and Stan Druckenmiller – very few investment managers boast a better 40+ year record than Marks.

These investing legends rarely speak.

But when they do – pay close attention.

Marks note was follow-up to his previous memo titled “Sea Change”

TL;DR

Investors need to re-think their longer-term investment strategies.

Marks is of the view the next decade (or more) won’t be the same as the last.

A rising tide is unlikely to lift all boats.

However, this also brings meaningful new opportunities for double-digit returns.

We just need to start looking in different ‘pockets’.

And it makes perfect sense…

For many years, investors have been effectively forced to chase returns in riskier assets (like stocks)

With rates held at zero – fixed income offered investors virtually no return (apart from the return of your capital).

I framed it this way:

It was a return OF your capital versus a return ON your capital.

Stocks on the other hand offered investors strong returns ON their capital – especially with rates so low.

But the tide has turned – as the US 10-year chart shows.

Today, you’re being rewarded for investing in debt (vs riskier equity).

Let’s Recap…

What do you consider to have been the most important event in the financial world in recent decades?”

Some suggest the Global Financial Crisis and bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, some the bursting of the tech bubble, and some the Fed/government response to the pandemic-related woes.

No one cites my candidate: the 2,000-basis-point decline in interest rates between 1980 and 2020.

And yet, as I wrote in “Sea Change“, that decline was probably responsible for the lion’s share of investment profits made over that period

Nothing has influenced (or inflated) the price of risk assets more than monetary policy (which includes the impact of QE – a tool to drive interest rates artificially lower)

Why has your house “tripled” in value the past “20 years”?

Interest rates!

I look at my own property portfolio.

Twenty years ago I bought a house in Annandale, Sydney for $600,000

Today it’s worth ~$2.0M (maybe a little more) – which translates to a compound annual growth rate of ~6%

I’ve seen similar rates of growth on the other houses I own over the same timeframe (where these houses are in Melbourne and Sydney) – most averaging a CAGR between 6-7% (excluding the 2-3% rental yield I also receive)

Rates continued to fall and prices (naturally) continued to go up at above average rates

Now this was luck (it certainly was not investment skill).

But the thing is – very few investors today have experienced a time where we didn’t have constantly declining and/or extremely low rates.

Marks makes the point:

Everyone who has come into the business since 1980 – in other words, the vast majority of today’s investors – has, with relatively few exceptions, only seen interest rates that were either declining or ultra-low (or both).

You have to have been working for more than 43 years, and thus be over 65, to have seen a prolonged period that was otherwise.

And since market conditions made it tough to find employment in our industry in the 1970s, you probably had to get your first job in the 1960s (like me) to have seen interest rates that were either higher and stable or rising.

Excluding property – I’ve only been investing in stock markets since the mid-1990’s

But I’m the inexperienced investor Marks is referencing.

I’m 52… with no experience investing in a climate of prolonged higher rates.

All I’ve seen are low rates trending down.

I financed my first house at just 8%… so I only know low rates.

Therefore, when Marks offers what is likely to come next – I am willing to listen:

- Economic growth may be slower (weighed down by debt and servicing costs);

- Profit margins may erode (due to a higher cost of debt);

- Default rates may head higher;

- Asset appreciation may not be as reliable;

- Cost of borrowing won’t trend downward consistently (though interest

- rates raised to fight inflation likely will be permitted to recede somewhat once inflation eases);

- Investor psychology may not be as uniformly positive; andBusinesses may not find it as easy to obtain financing.

In other words, the rules of the game have fundamentally changed.

He adds:

“I see no reason why short-term interest rates five years from now should be appreciably higher than they are today. But still, I think the easy times – and easy money – are largely over.

How can I best communicate what I’m talking about?

Try this:

Five years ago, an investor went to the bank for a loan, and the banker said, “We’ll give you $800 million at 5%.”

Now the loan has to be refinanced, and the banker says, “We’ll give you $500 million at 8%.”

That means the investor’s cost of capital is up, his net return on the investment is down (or negative), and he has a $300 million hole to fill.

So What Strategies Will Work?

“Never confuse brains and a bull market”

How many property (and stock) speculators pat themselves on the back thinking they are a genius after some windfall gain?

I know a few…

As I said earlier – a rising tide will often lift all boats (even boats which should have never set sail!)

If you failed to make a lot of money the past two decades – it was either due to:

(a) bad decision-making; and/or

(b) really bad luck on the asset you purchased (which happens!)

It certainly wasn’t a high cost of funding which caused your error.

But as Marks contends – will asset ownership be as profitable in the years ahead as in the 2009-21 period?

Will leverage add as much to returns if interest rates don’t decline over time; or if the cost of borrowing isn’t much below the expected rate of return on the assets purchased?

Whatever the intrinsic merits of asset ownership and levered investment, one would think the benefits will be reduced in the years ahead.

And merely riding positive trends by buying and levering may no longer be sufficient to produce success. In the new environment, earning exceptional returns will likely once again require skill in making bargain purchases and, in control strategies, adding value to the assets owned.

Therefore, Marks argues that leaning into lending, credit or fixed income investing should be correspondingly better off.

Why?

Because you are now being rewarded (handsomely in some cases) for buying debt.

Higher potential returns are (finally) here…

Frustratingly, we had to wait almost two decades – but they’re here.

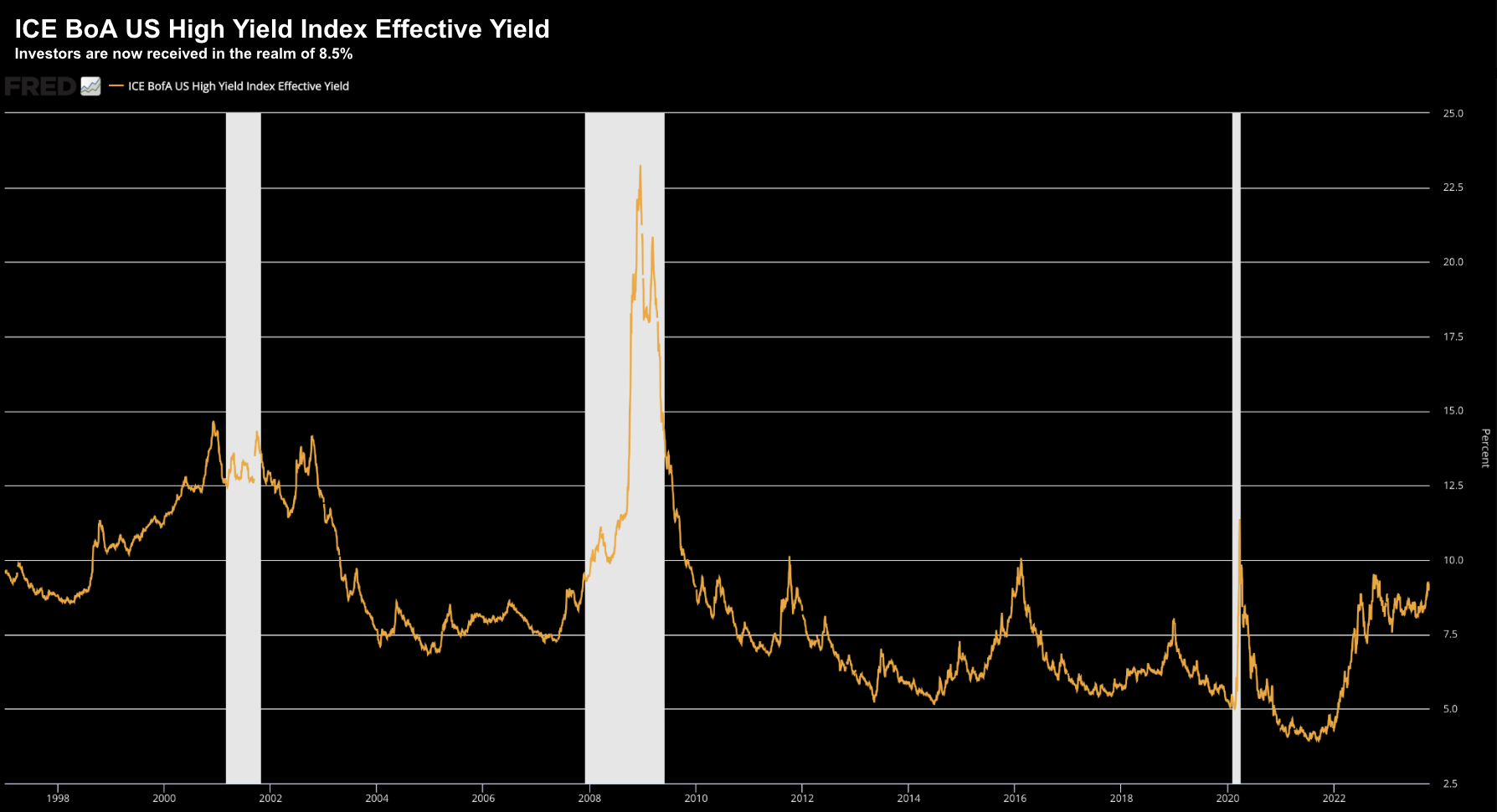

Marks points out that in early 2022, high yield bonds (for example) yielded in the 4% range – not a very useful return.

Today, they yield more than 8%, meaning these bonds have the potential to make a great contribution to portfolio results.

Sure – there will be defaults. Many I expect. In fact, this year has seen more corporate defaults than any year since 2011.

However, many vehicles (ETFs) offering exposure to high yield debt (eg HYG among others) are designed to compensate for the risk of default.

Put it this way – if you own the S&P 500 Index (eg SPY) and several companies go bankrupt – that doesn’t mean your investment in Index Fund collapses. Those companies are removed and others are added.

Now in addition to the 8% type yields – which is designed to compensate for the risk – this is exclusive of any potential capital appreciation should rates fall.

The same is generally true across the entire spectrum of non-investment grade credit.

Marks highlights that the S&P 500 Index has returned just over 10% per year for almost a century (including dividends).

Let’s compare that with the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Constrained Index – which now offers a contracted yield of ~8.5%

He adds the CS Leveraged Loan Index offers ~10.0%

In other words, yields from these non-investment grade debt investments are getting close to historical returns from equity.

But unlike equity – these are contractual returns.

A Turning Point for Marks

When I shifted from equities to bonds in 1978, I was struck by a major difference.

With equities, the bulk of your return in the short or medium term depends on the behavior of the market.

If Mr. Market’s in a good mood, as Ben Graham put it, your return will benefit, and vice versa.

With credit instruments, on the other hand, your return comes overwhelmingly from the contract between you and the borrowers.

You give a borrower money up front; they pay you interest every six months; and they give you your money back at the end.

And, to greatly oversimplify, if the borrower doesn’t pay you as promised, you and the other creditors get ownership of the company via the bankruptcy process, a possibility that gives the borrower a lot of incentive to honor the contract.

The credit investor isn’t dependent on the market for returns; if the market shuts down or becomes illiquid, the return for the long-term holder is unaffected.

The difference between the sources of return on stocks and bonds is profound, something many investors may understand intellectually but not fully appreciate.

But whilst credit investing offers these advantages – you still need the returns to adequately compensate you for lending the money (as it’s effectively opportunity cost).

As mentioned in my preface, it’s been over a decade since investors were offered these returns (i.e., where they competed with equities)

Marks says that Charlie Munger exhorts us to “invert,” or flip questions like this:

“What are the arguments for not putting a significant portion of our capital into credit today?”

Default risks?

Well you can minimize that via ETF exposure.

What are the other reasons?

This is what I have been doing…

Putting it All Together

In summary, investors should start to re-think their investment strategy.

Equity returns will unlikely match what we’ve seen the past decade with rates higher for much longer.

Three reasons to consider allocation to debt investing:

- Non-investment grade debt is now highly competitive versus the historical returns on equities,

- This returns will exceed many investors’ required returns or actuarial assumptions, and

- Returns from debt are much less uncertain than equity returns.

What do you think are reasons why this doesn’t deserve a solid allocation (e.g. 15% to 20%) in your portfolio?