- Why does the Fed need to cut?

- Economic (and financial) stimulus goes beyond the Fed

- What’s actually ‘restrictive’ about financial conditions today?

Markets have a spring in their step in the aftermath of the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting on March 19-20.

Despite a couple of flattish days recently – the S&P 500 went from 5133 at the open on the first day of the meeting to 5260 on the morning after the meeting.

That’s a sizable gain in two days – especially given what we’ve seen in the weeks prior.

It’s literally been straight up… where the weekly RSI has been overbought for 10 weeks

March 26 2024

If anything, they intend on adding to it by:

- Cutting rates three times this year (starting as early as June or July); and

- Reducing QT “fairly soon” (currently $95B per month)

The renewed sense of ‘dovishness’ is curious.

For example, on one hand, the Fed has increased their forecasts for economic growth this year (and next).

I mentioned after the meeting how Powell expects the U.S. economy to grow 2.1% this year (up from December’s 1.4% projection) — before ticking down slightly to 2.0% in 2025 and remaining at that level through 2026.

But…

For reasons I can’t explain, Powell also sees a need to stimulate the economy with rate cuts and reduced quantitative tightening?

Why?

I don’t get it (and it turns out I’m not alone).

What does the Fed see that we don’t?

And what would make the Fed so confident their 2-year war with unwanted inflation (above 2%) has been won?

Why Is Powell So Confident?

One question investors should ask is what’s the probability of inflation coming down at the velocity the Fed expects?

Greater than 80%? 50%? Less?

Hard to say…

But from Powell’s language, I would say he is closer to the 80% range than he is 50%.

Now, to help your decision, consider one of the largest inputs into inflation – the price of oil.

March 26 2024

‘Texas tea’ is up 22% from its December lows of ~$67/b.

Not surprisingly, energy was the primary culprit for the hotter-then-expected inflation prints over Jan and Feb.

Now what if WTI Crude continues on its path to $90/b over the summer months?

How will this influence CPI?

Powell touched on where inflation is as part of his address:

“The economy has made considerable progress toward our dual mandate. However, inflation is still too high. It remains above our longer run goal of 2 percent.”

Why Cut So Soon?

From mine, this presents a real dilemma for the Fed.

We know cutting rates is potentially inflationary.

On the other hand, if the Fed are to maintain their “higher for longer” stance – it may stifle lending, investment and economic growth

Here’s Powell on balancing the two sides of the same coin:

“The risks are really two-sided here… If we ease too early, we could see inflation come back. … If we ease too late, we could impact the economy negatively.

What we’re looking for now is confirmation that that progress will continue… We’re looking for more good data and we would certainly welcome it.”

But do you see the assumption Powell is making?

He is implying that interest rates and inflation have a reciprocal relationship.

Do they?

I think there is some relationship with rates – but how much of that is entirely causation?

That’s not something Powell (or any economist) can answer.

You see, interest rates are a blunt instrument.

And as I will explain below – Fed policy is just part of the equation when it comes to the borrowing and spending habits of 330M people.

That said, there is an assumption in Powell’s language that current “high” interest rates (where high is relative) will put the inflation genie back in the bottle.

And from there, that will clear the path for more rate cuts, leading to stronger growth etc etc.

We will see…

But for me it’s not greater than a 50% probability.

Let’s come back to why cut soon (e.g., June or July)?

Looking back through Powell’s Q&A post his prepared remarks – he may have offered a clue on why he feels the time to act could be soon.

For example, here is more language from the Chair:

And in terms of the timing [of QT reduction], I said “fairly soon.” I wouldn’t want to try to be more specific than that.

But you get the idea. The idea is—and this is in our—in our longer-run plans, that we may actually be able to get to a lower level, because we would avoid the kind of frictions that can happen.

Liquidity is not evenly distributed in the system. And there can be times when in the aggregate reserves are ample or even abundant, but not in every part.

And those parts where they’re not ample there can be stress. And that can cause you to prematurely stop the process to avoid the stress. And then it would be very hard to restart, we think. So something like that happened in [20]19, perhaps.

So that’s what we’re doing. We’re looking at what would be a good time and what will be a good structure. And, you know, “fairly soon” is words that we use to mean fairly soon.

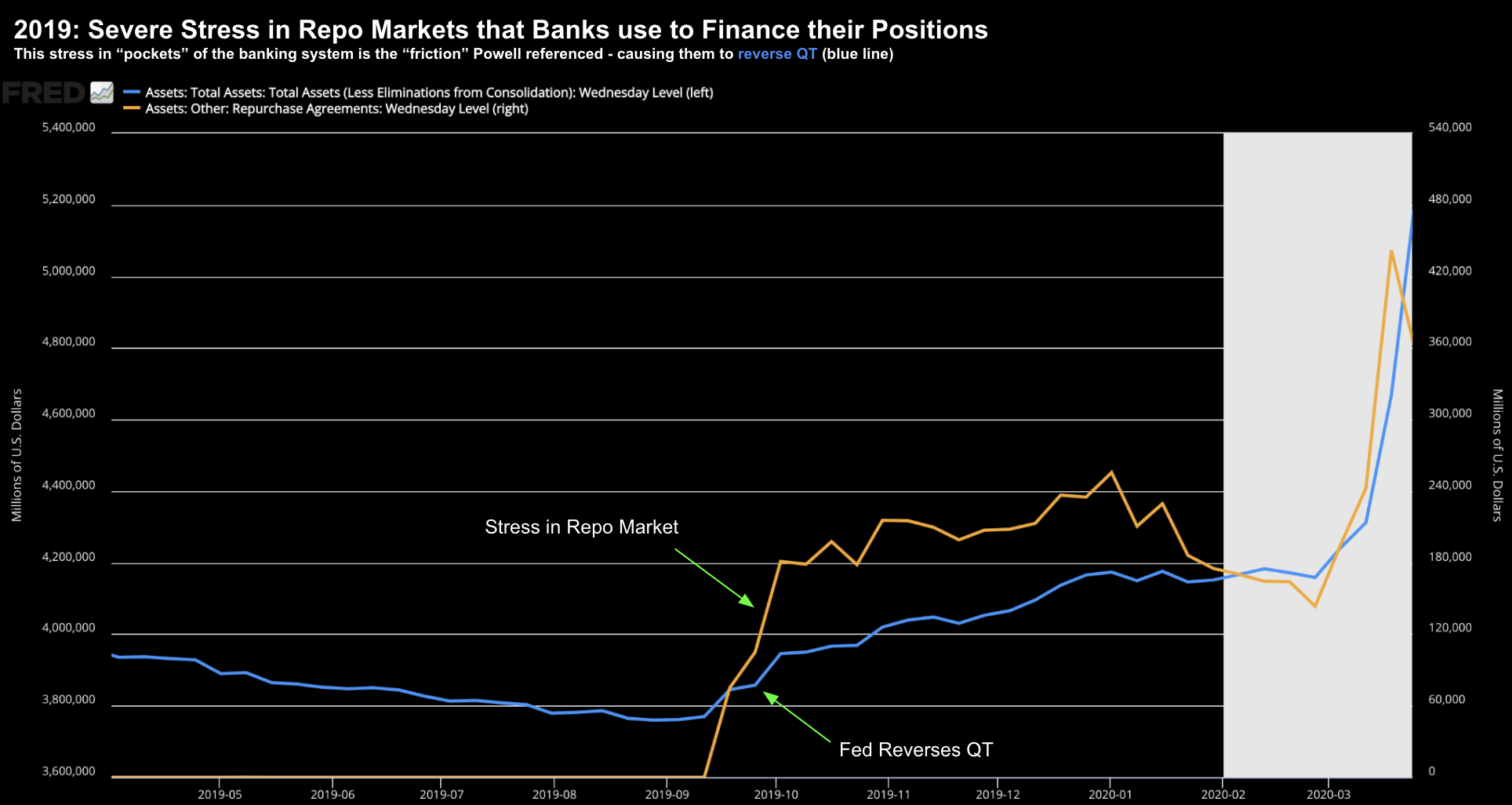

The “friction” Powell touches on is the financial stress we saw in the banking ‘repo market’.

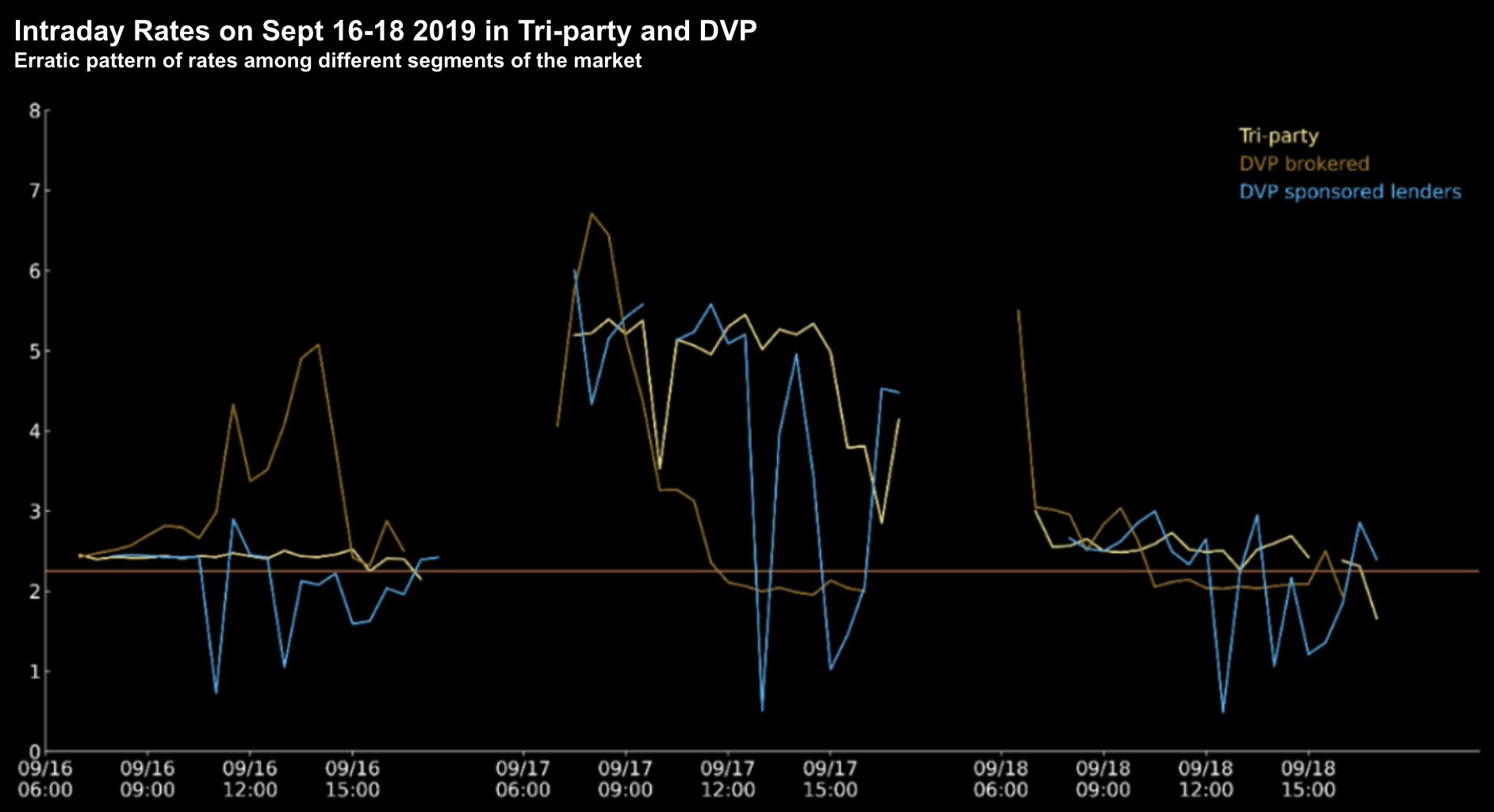

Without getting too wonky – around mid-September 2019 – repo rates spiked dramatically, rising to as high as 10% intraday.

The disruption began on September 16—the day of Treasury settlement – which coincided with corporate tax deadlines.

The combination of these two developments resulted in a large transfer of reserves from the financial market to the government, which created a mismatch in the demand for and the supply of repo that drove rates higher.

This effectively forced the Fed to intervene…

Below shows the Fed’s reversal of QT (blue line) in response to the lending stress:

Rates in the repo market are highly dependent on the supply of Treasuries and reserves.

However, by mid-September 2019, aggregate reserves had declined to a multiyear low of less than $1.4 trillion while net Treasury positions held by primary dealers had reached an all-time high.

As a result, the reserve constraints on banks and bank-affiliated dealers may have played a contributing role.

Therefore, the Fed needed to reverse its position on QT and address the liquidity shortfall – providing an additional $10 billion into the repo market.

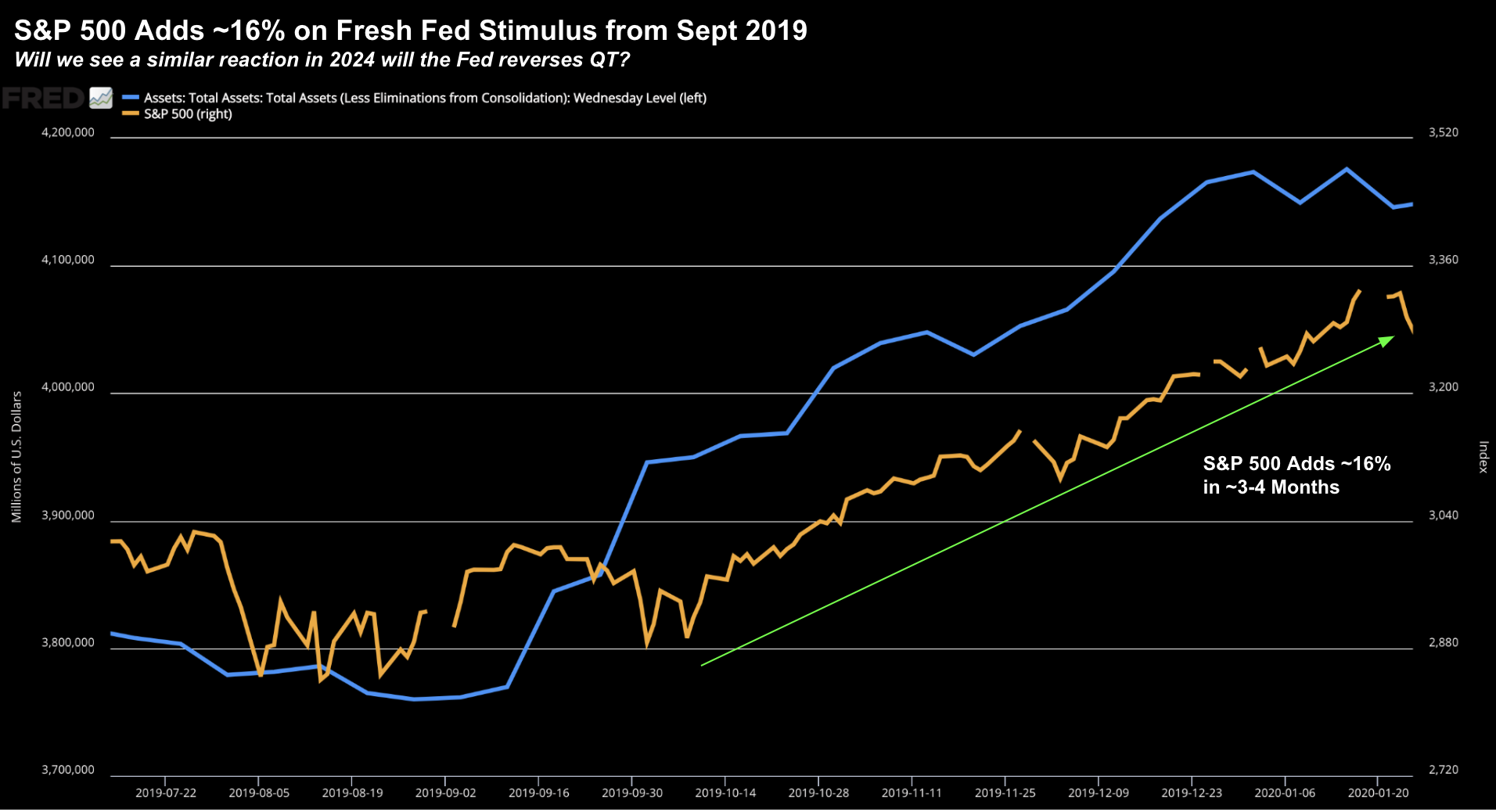

And whilst stock markets were not largely aware of the stresses building in the banking system – they certainly noticed the Fed adding stimulus.

The S&P 500 added ~16% in less than 4 months:

I’ll ask the question again…

What does Powell see in the market (or is worried about) that we don’t?

Potential financial stress? Economic weakness? Something else?

Irrespective, as an investor, if he’s thinking about adding further stimulus – that’s waving a red flag to a raging stock bull.

Restrictive Rates… Really?

Beyond the balance sheet (and tapering of QT) – Powell also often refers to rates being “restrictive”.

But again, restrictive is relative.

It only means something when measured against what is considered neutral.

But what is the neutral rate (and how is it defined)?

And specifically, on what basis does Powell think rates are restrictive?

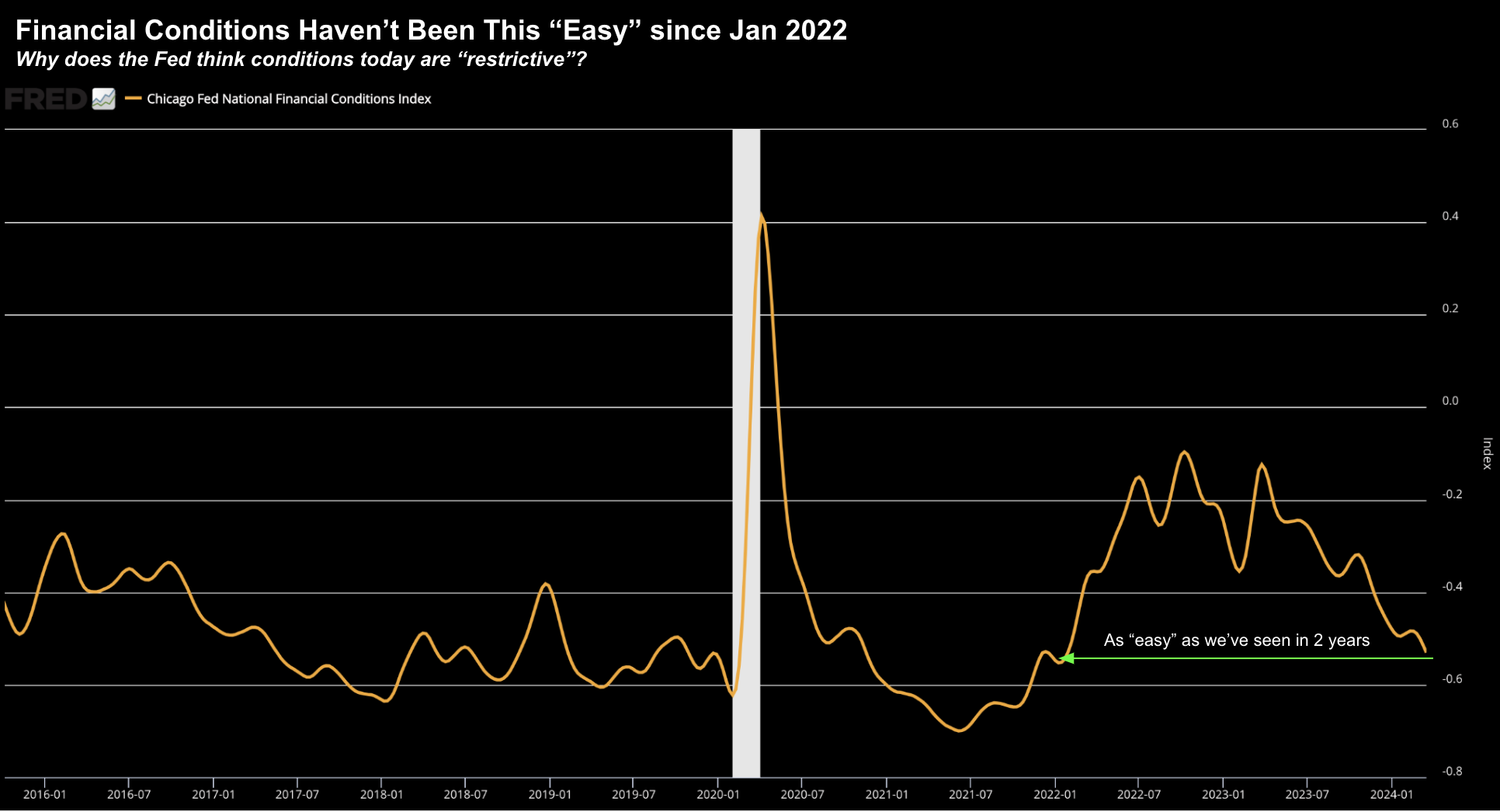

For example, take a look at the Fed’s own measure of financial conditions (and the recent monthly trend):

As I’ve highlighted in the past, financial conditions are about as accommodative as we’ve seen since January.

By comparison, from mid-2022 through to Q1 2023, financial conditions were actually restrictive.

Naturally, the price action in the S&P 500 was sideways to negative.

But today, when we look at what’s going on with speculative assets, are they acting as though rates are restrictive?

From mine, there is still a lot of liquidity “washing around” in the economy.

And whilst short-term rates may be considered high relative to where they were a couple of years ago (i.e., zero) – there are other factors at play.

Consider fiscal stimulus.

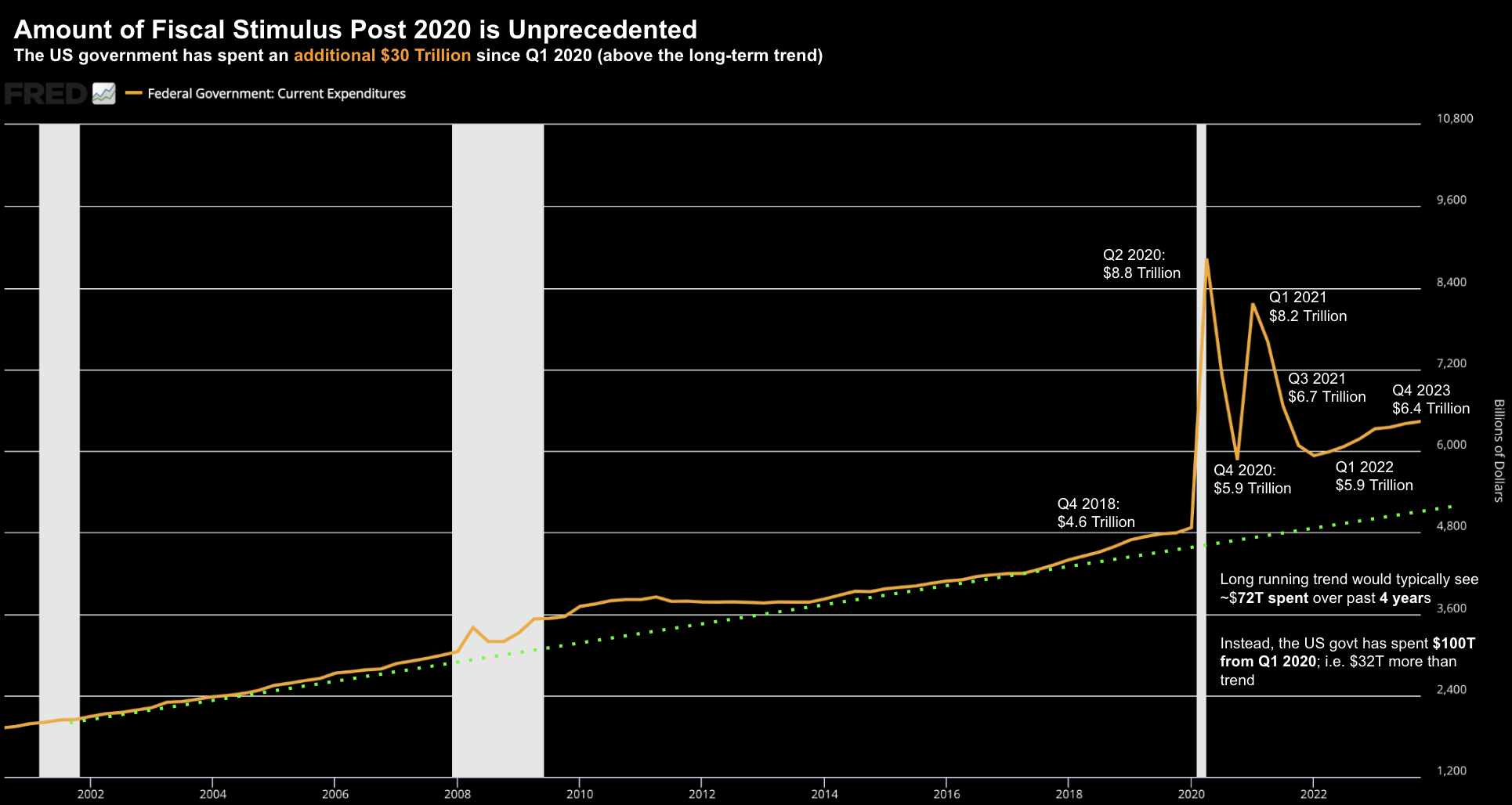

Quick math shows the US government has borrowed (and spent) roughly $30 Trillion incremental dollars (post Q1 2020) beyond what would ‘typically’ be incurred (e.g., ~$4.8T to $5.0T per quarter)

March 26 2024

My point is the Fed is not the only driver of the economy; and/or the financial markets (you might even suggest perhaps not even the most important?)

Yes, the actions of Powell should not be ignored. Far from it.

They matter.

But given the excesses in government borrowing and spending (post 2020) – how is that not extremely accommodative to the broader economy (and in turn, risk assets)?

I didn’t see this mentioned by Powell.

To finish the point – Larry Summers – former US Treasury Secretary – echoed my sentiment as part of this Bloomberg interview:

My sense is still that the Fed has itchy fingers to start cutting rates and I don’t fully get it,” Summers said during an interview with Bloomberg on Thursday, citing key economic indicators that seem at odds with the Fed’s appearance of being “in such a hurry” to loosen policy.

“We’ve got unemployment if anything below what they think is full capacity. We’ve got inflation, clearly even in their forecast for the next two years above target. We’ve got GDP growth rising if anything faster than potential.

We have financial conditions, the holistic measure of monetary policy at a very loose level.”

Exactly!

So why the need to cut?

Putting it All Together

Powell may have an itchy (trigger) finger.

This is why I was surprised by his (continued) dovish rhetoric and contradiction(s).

On the one hand, growth is accelerating, inflation is falling and we have a strong labor market.

Excellent!

But we still need to cut rates an taper QT.

I must be missing something (or I’m just thick) – but for me – it’s hard to understand why the Fed is so keen to pull the trigger.