Words: 2,085 Time: 9 Minutes

- Moats and long-term durability

- It’s not just what we buy – it’s critical how much we pay

- Rational thinking starts with thinking probabilistically

With markets at record highs – trading at very high valuations – I felt it was timely to revisit investing lessons from Charlie Munger.

Sadly, Charlie passed away late last year – just shy of his 100th birthday.

For those less familiar, after initially being trained as a meteorologist during World War II – he decided to pursue a career in law – creating a very successful law firm.

However, after being introduced to Warren Buffett, he was talked into a career in business.

The rest – as we know – is Berkshire Hathaway history.

Whilst Charlie was an incredible investor – what I loved most was his ability to draw insights from many disciplines – which included the study of psychology, economics, physics, biology, history, architecture among other things.

This enabled Charlie to develop a lattice of “mental models” to cut through difficult problems.

Over the years, I’ve found Charlie’s insights into investing, business and life not only rare but generally correct. What’s more, they stand the test of time.

Now when he was asked about the secret to his success – Munger answered: “I’m rational”

What follows is a summary of a speech he gave on investing… which centers on three pillars:

- The Importance of Moats and Durable Competitive Advantage

- Valuation and the Challenge of Finding the Right Price; and

- The Role of Probabilistic Thinking

Importance of Moats and Durable Advantage

Often readers will hear me talk about the importance of investing in quality businesses.

But what does ‘quality’ mean?

From my lens, it includes characteristics such as (not limited to):

- A history of strong free cash flow yield (e.g., 7-8%+ for at least three years)

- History of high average return on invested capital (e.g., ROIC 20%+)

- History of low weighted average cost of capital (e.g., WACC less than 10%)

- Low levels of total debt (which includes off-balance sheet items such as operating leases and pension funds)

- A record of growing revenue and earnings; and

- The ability to produce products and services which their competitors cannot easily replicate (i.e. a strong competitive, durable moat)

Assuming you discover a company which satisfies the above (which is difficult) – from there it’s a question of what you’re willing to pay for future cash flows.

Now generally when a company is consistently delivering strong free cash flows with consistently high ROIC at low WACC – quite often that will ‘map’ to a business than enjoys a healthy moat.

In other words, it’s very difficult for other companies to emulate what that business is doing.

Apple is a great example.

Its average ROIC over the past 3 years is an incredible 42%

Its WACC this year is around 11% (higher than its peers due to its hardware business).

And if you subtract that WACC from its ROIC – you get 31.1% – something very few other companies are able to achieve.

Now this is also a company with more than 2B very loyal users on their iOS platform (across iPhones, iMac, iPads and more).

But given the “honeypot” Apple has created – they have seen many companies try to emulate their unique software and hardware ecosystem.

None have come remotely close.

Samsung, Microsoft, Amazon, Google and Meta have all tried.

Yes, other tech companies may boast 2B+ monthly active users across their various services or platforms (e.g., Microsoft, Meta, Google and Apple).

But none replicate what Apple has been able to achieve with its unique hardware bundle.

This gives Apple an incredible sustainable competitive advantage that protects it from competition (enabling them to enjoy the ROIC above).

However, whilst Apple enjoys a (well deserved) competitive moat today – it’s very difficult to say if that will be the case in say 10 or 20 years.

For example, the rapid transformation going on with AI will lead to disruption.

What specifically is disrupted remains to be seen – but we know things will not be the same in a decade.

Consider what we’ve seen in the past…

Up until the 1990s – Kodak was the world’s leading photography company.

However, it failed to adapt to digital imaging which saw the company eventually fail.

Their management made the (poor) decision to try and defend their high-margin film-based market – rejecting the disruptive digital play.

It took less than 10 years and were a shadow of the company they were.

Ford and General Motors are another example.

Both dominated the auto industry for many decades after the 1920s.

However, their competitive moat post the 1970s was disrupted by Japanese, German and Korean manufacturers — as they mastered the supply-chain — producing quality cars at much lower costs. Ford and GM still compete – but at very small margins given how competitive the industry is.

There are countless other examples….

Munger reminds us that the dynamics of capitalism are Darwinian – where businesses that once thrived can be obliterated by technological change.

Again, it doesn’t take Nostradamus to foresee how AI will transform everything we do.

But from an investment perspective – the core issue is not just identifying companies with strong operating moats – but understanding how durable those moats are in the long term.

For example, I think Apple will be a tremendous vehicle for AI distribution over the next ~5 years.

The way I see it – this is how most non-tech folks will discover applications like “ChatGPT” etc – when they eventually surface on the iPhone (e.g., “Apple intelligence”)

That will be powerful.

However, how we consume these services will change over time.

For example, what’s to say phones will be the primary communication interface in 10 or 20 years?

As Munger pointed out, it’s easy to highlight a company like “Apple, Meta, Google or Amazon” which are doing well now (i.e., something which is seen)

However, what’s unseen (and much harder to predict) is whether they will continue to thrive, especially as market conditions and technology evolve.

To that extent, we need to be extremely mindful of how much we pay for future cash flows.

For Apple, that multiple is a whopping 32x times earnings.

The greater the multiple paid – the higher your risk – regardless of how strong their return on capital is.

Which is a good segue to Munger’s second point…

Challenge of Finding the Right Price

Evaluating what to pay for a company’s intrinsic value is difficult.

For example, is paying 32x for Apple’s forward earnings good value?

Many seem to think so.

However, this is the most important question you can ask.

By way of example, I summarized the 20 chapters of Ben Graham’s invaluable ‘The Intelligent Investor’ for readers here (a good place to start if you’re not familiar with valuation models)

Chapter 18 is particularly useful – where Graham compares and contrasts 8 case studies

But this is only one approach…. there are others.

For example, I look at the key metrics I flagged above (such as free cash flow yield, ROIC, WACC etc)

In addition, I check valuation multiples such as:

- Price to (adjusted) earnings;

- Price to book value; and

- A simplified Q-Ratio (i.e., market capitalization divided by its book value)

Regardless of your approach – you need to evaluate what you believe the company is truly worth.

But generally, companies with the qualities I mentioned earlier are typically expensive.

Munger warns when this is the case – it will render such investments less attractive (a point also made by Graham)

Let’s come back to Apple….

This is why I meaningfully reduced my holdings to ~2% of my portfolio this year.

It traded around 30x forward and I decided to reduce my exposure. Warren Buffett took a similar path last quarter – selling 66% of his stock (however it’s still his largest position)

Munger felt that most investors focus too much on identifying good companies; and then fail to account for the price they’re paying.

This leads to situations where a stock’s price may reflect its current success, leaving little room for future growth.

And that’s the question I have with the Mag 7; i.e., names such as Apple, Nvidia, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Tesla etc.

Yes – they will most likely grow.

But I don’t think that growth will be at the same velocity.

Therefore, from a valuation perspective, those risks are now increasing to the downside (especially if they don’t deliver on the AI hype)

Munger highlights the importance of seeking investments where the price is justified relative to the company’s intrinsic value and future potential.

Echoing the point I made earlier – the real challenge lies in finding good companies that are not overpriced.

In addition, Munger expressed skepticism about the so-called “efficient market theory” – noting that the market doesn’t always accurately price stocks.

I could not agree more….

My best guess is the market is efficient “80-90%” of the time.

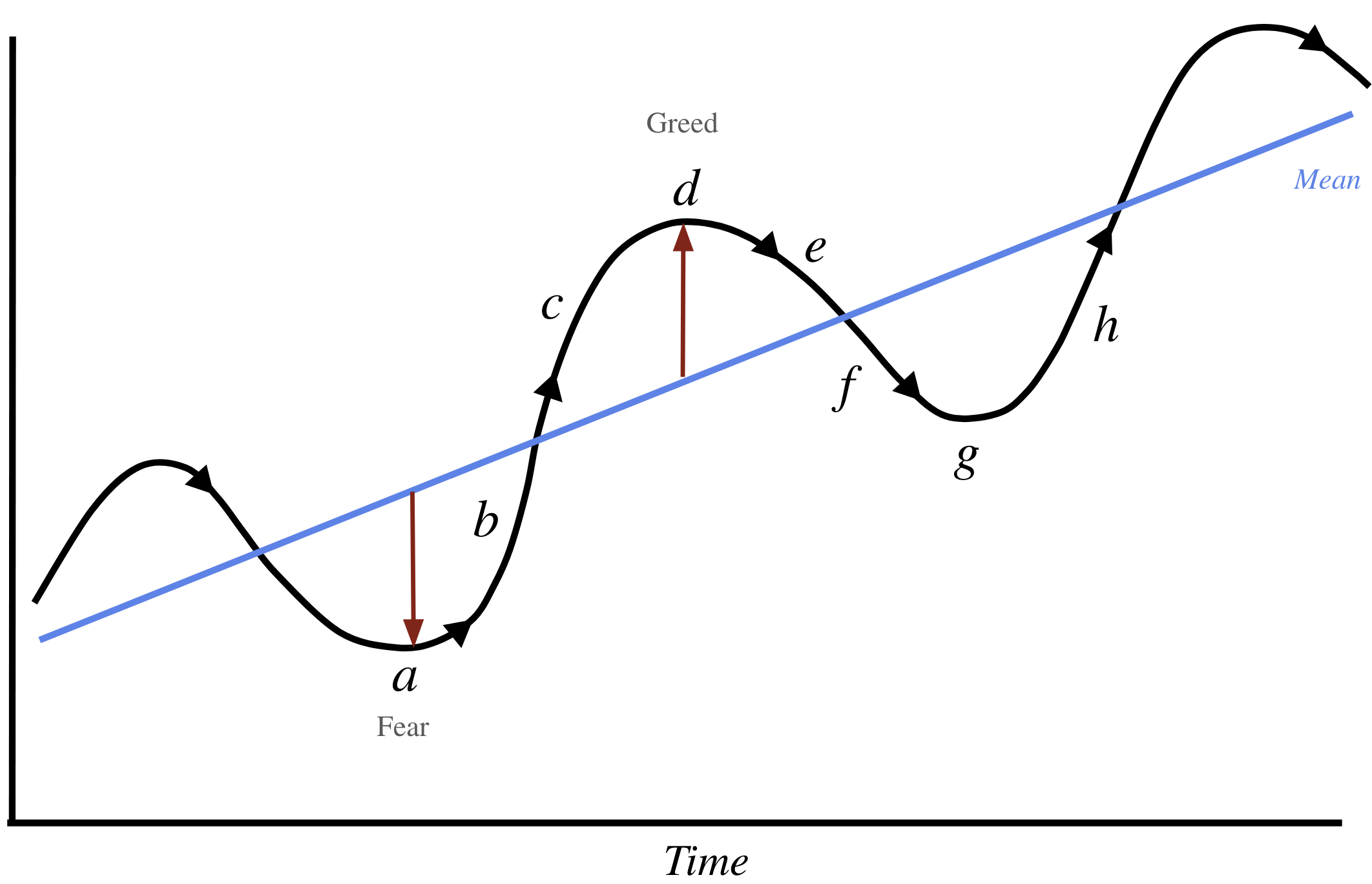

However, for the balance of the time, investor emotion takes over (fear, greed and other self-defeating behaviors) where the market is terribly inefficient.

But it’s this inefficiency where opportunity is created.

When investors are emotional – they make poor decisions. This opens the door for the patient (savvy) investor who understands what a company is actually worth (i.e., where there is real long-term value)

Howard Marks talks to market inefficiency in his great book “Mastering the Business Cycle” – something to add to your Christmas reading list.

The Role of Probability and Decision-Making

As our final lesson, Munger also stressed the importance of thinking probabilistically when making decisions.

Why?

Apart from death and taxes – nothing else we do is certain.

And given we cannot know what will happen in the future – then all we have are probabilities.

As part of Munger’s array of mental models – he draws from the work of 17th-century mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat.

As an aside, to better understand how these two individuals shaped our history (and financial markets) – I recommend reading “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” (one of the best books you will read)

For quick context, in 1654, Pascal’s friend, a gambler, sought his help in understanding why he kept losing money.

This prompted a series of letters between Pascal and Fermat, which laid the foundations for modern probability theory.

Their work focused on calculating the odds of various outcomes and understanding how to make decisions based on uncertainty.

This is how the insurance industry operates today.

This approach transformed the way people think about risk and decision-making, influencing fields like economics, finance, and investing.

Drawing heavily on the work of Pascal and de Fermat – Munger would go to lengths to explain how probabilities can lead to better decision-making.

Repeating what I said above – the approach involves evaluating the likelihood of various outcomes and making informed decisions based on the most probable results.

For Munger and Buffett – this has been one of the cornerstones to their success. Probabilistic thinking remains at the core of rational decision-making.

Munger would remind us that investing isn’t about finding certainties (that’s impossible). However, what it is about is minimizing your errors and focusing on the “easy decisions”

Easy decisions are those with low-risk, high-probability bets that offer the best chance for long-term success.

Case in point – buying an asset which is trading close to its intrinsic value (or its book value) – creates a margin of safety in the event your thesis is wrong and/or market conditions turn less favorable.

For further reading – see my summary of Chapter 11 of ‘The Intelligent Investor’ – where Graham talks to why a margin of safety is imperative.

💥 Putting it All Together

In summary, investing is a dynamic process that requires patience, discipline, and a deep understanding of both businesses and the market.

Knowing that we cannot possibly know the outcome, using probabilistic thinking will help reduce costly mistakes.

After Charlie passed away, Warren Buffett called him the “architect” of Berkshire Hathaway.

Warren referred to himself as merely the contractor (a measure of his humility).

Munger was well known for his multidisciplinary approach to problem-solving, drawing insights from psychology, economics, physics, and more.

This lattice of “mental models” helped him make better decisions in business and life.

In investing, he emphasized the importance of finding companies with strong “moats” or competitive advantages – while also stressing the challenge of determining their durability over time.

But it’s not just a matter of identifying companies with strong metrics and operating moats.

That’s where the work starts…

Valuation is crucial.

We should avoid overpaying for great companies – creating a margin of safety in case things don’t work out.

Ask yourself – what are you paying to own equities today?