The Intelligent Investor

Part 5: The Defensive Investor: Stock Selection

Words: 1,088 Time: 5 Minutes

“Human felicity is produced not so much by great pieces of good fortune that seldom happen, as by little advantages that occur every day“

– Benjamin Franklin

💥 Why This Matters

- Valuation matters: Even when stocks have advantages (e.g., like inflation protection) – overpaying for an asset can eliminate those advantages

- Growth stocks are challenging: High-growth companies are tempting, but their prices often get ahead of themselves. Invest carefully in growth names.

⚖️ Taking a Balanced Perspective

Graham acknowledges that stocks offer potential for attractive returns and inflation protection, but stresses the importance of careful selection and valuation to mitigate risks.

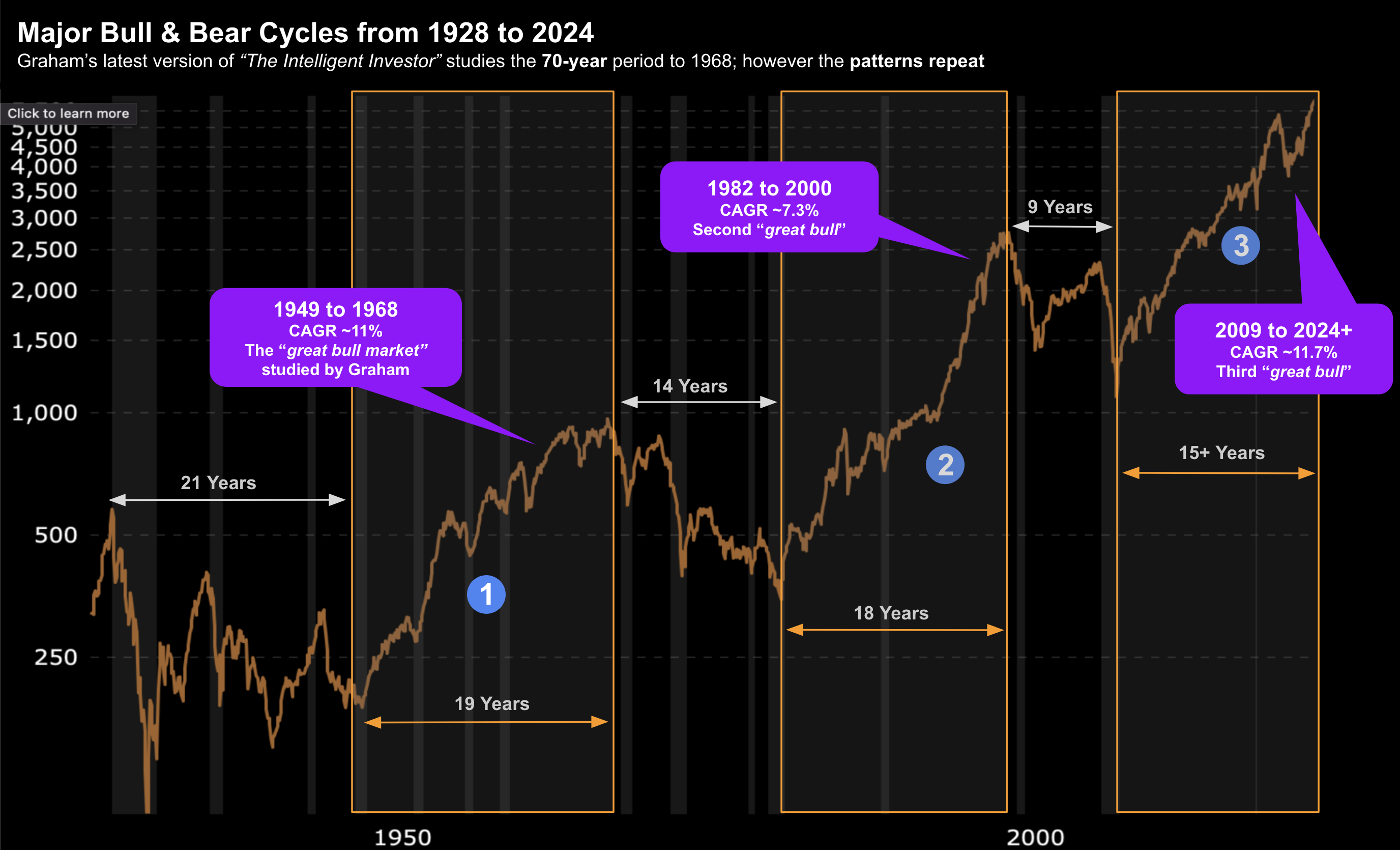

In the first edition of his book (1949), Graham advocated for including stocks in portfolios, as equities were seen as speculative after the market crash from 1929 to 1948, which shattered investor confidence.

Fast forward almost seventy years – and today’s investor would find it very difficult to comprehend approximately two decades of negative returns.

For example, since the depths of the financial crisis in 2009, investors have seen an average ~12% annual growth (exc. dividends) for the past 15 years (labeled “3” below).

Rarely have investors experienced such a long run of stellar returns…

Highlighted are three bull markets of the past 100 years (where CAGRs are exclusive of dividends):

- 1949 to 1968 – 19 years – CAGR of ~11%

- 1982 to 2000 – 18 years – CAGR of ~7.3%

- 2009 to 2024* – 15 years (in process) – CAGR ~11.7%

However, extended booms (such as what we have today) also create an illusion of safety and fueling excessive investor enthusiasm.

This exuberance, Graham cautions, can lead to excessive valuations and increased risk for investors who buy at inflated prices.

🪖 Stocks: Two Key Advantages

1. Inflation Hedge: Stocks often rise with inflation, unlike bonds, whose fixed returns are eroded by inflation. During inflationary periods, high-quality stocks and ownership assets (e.g., property, private equity) are valuable

2. Higher Average Returns: Stocks generally deliver higher returns than bonds over the long term due to dividend income and capital appreciation

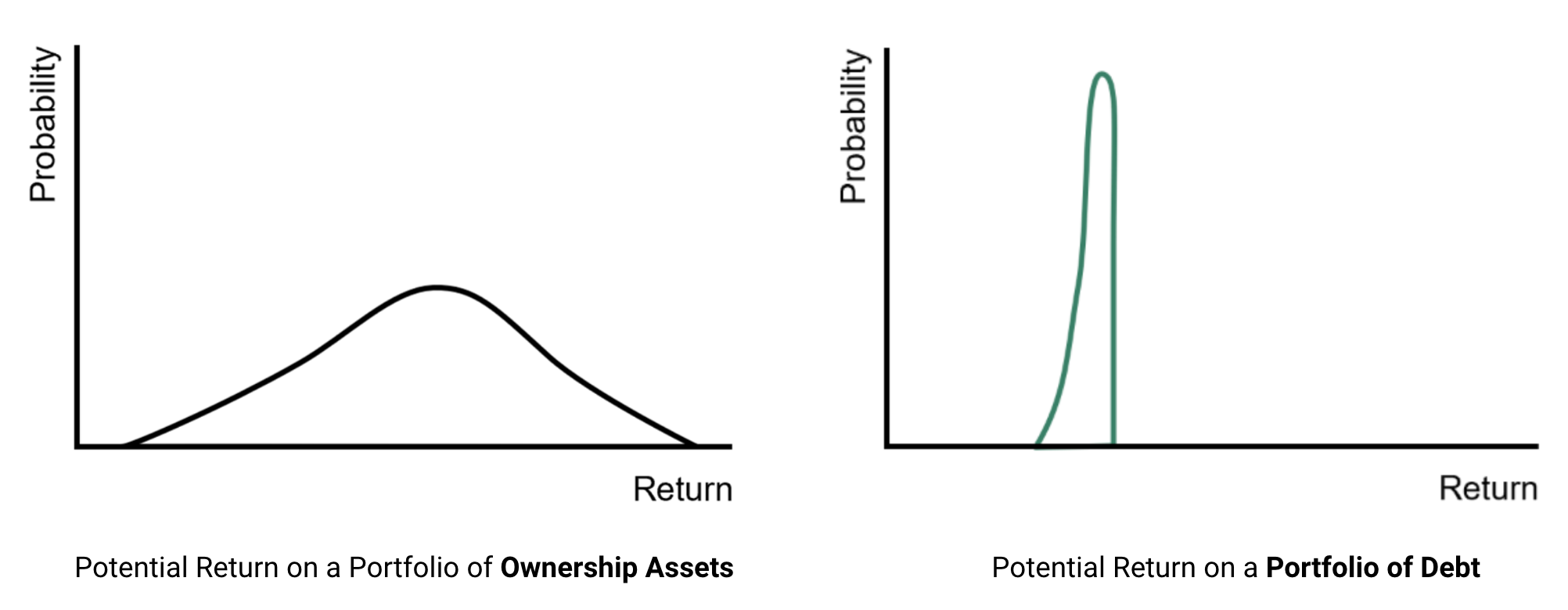

The critical consideration is the associated risk; i.e., as ownership assets (stocks) tend to have higher expected returns to compensate for the risk (see related post here)

Another way to understand risk/reward profile between ownership and debt assets are via distribution (risk) curves (from Howard Marks):

Quoting Marks:

“Ownership assets (e.g. stocks or property) typically have a higher expected return, greater upside potential, and greater downside risk.

Everything else being equal, the expected returns from debt are lower but likely to fall within a much tighter range”

😥 Valuation: Avoiding Overpaying

During bull markets, it’s easy to overpay.

For example, investors who felt they missed the first part of the rally – are tempted to chase the price (i.e., the fear of missing out)

Graham stresses the importance of maintaining independent thought and resistance to this pressure. He outlines four rules to avoid overpaying:

- Adequate Diversification: Hold a diversified portfolio of 10 to 30 different stocks to reduce company-specific risk.

2. Large, Prominent, and Conservatively Financed Companies: Focus on well-established companies with strong financial positions and a history of stable earnings

3. Long Record of Dividend Payments: Select companies with a consistent track record of paying dividends, indicating financial stability and shareholder-friendly management.

4. Reasonable Price-to-Earnings Ratio: Avoid overpaying for stocks by limiting the purchase price relative to average earnings over a period of several years (e.g., a minimum of 3 years; and ideally up to 10 years)

We explore these (and other) rules in greater detail in Chapter 18 with 8 contrasting case studies.

📈 Growth Stocks: A Cautious Approach

Growth stocks, often with high valuations, pose challenges for risk-averse investors.

While their potential for high returns is appealing, the volatility of such stocks makes them unsuitable for conservative approaches.

For example, tech companies like Nvidia or Amazon can see dramatic price swings. A defensive investor, prioritizing stability, would find such stocks risky if overvalued.

The key is aligning choices with your risk tolerance and investment horizon.

For example, an individual nearing retirement may be less willing to accept volatility than a younger investor, who can afford to wait for growth.

Graham warns against overpaying for growth, citing how high-flying stocks can still lose value despite strong earnings.

For example, in 2022, many tech stocks lost 30-50% of their value, similar to the dot-com bust of 2000, where even profitable companies like Cisco lost over 90% (and never recovered).

For more defensive investors, Graham recommends focusing on undervalued, financially sound companies. These may not have high growth prospects, but they offer more stability and less risk.

🙋 Tailoring Strategies to Individual Circumstances

Graham emphasizes aligning investment strategies with individual circumstances.

Investors with limited financial expertise or a need for capital preservation should focus on high-quality, undervalued stocks and bonds.

However, more experienced investors with higher risk tolerance may opt for a more aggressive strategy, such as growth stocks.

That said, Graham warns against excessive speculation and emphasizes thorough analysis (irrespective of whether you are a more aggressive or defensive investor).

For those without the time or skill to analyze markets, investing in a low-cost index fund at regular intervals is a simple and effective strategy.

🎢 Risk: Price Fluctuation vs Permanent Loss

Short-term declines are not true risk if the investment’s underlying value remains intact.

The real risk is overpaying for assets or investing in companies with a high likelihood of financial deterioration.

By focusing on undervalued, financially sound companies, investors can mitigate these risks and achieve long-term success.

Graham refers to this as the “margin of safety” approach, which will be explored further in subsequent chapters.

For me, the average holding time for a stock is around 3-4 years, though it can be longer.

When I take a position, I’m prepared for price declines and use them to increase my stake, provided the company’s valuation story remains intact.

The key lesson is being comfortable with being wrong. A 30% drawdown shouldn’t change your conviction if the company’s fundamentals remain strong.

4 Key Takeaways

4 Key Takeaways

- Graham advocates for a defensive approach to stock investing

- He emphasizes minimizing effort and maximizing safety, recommending low-cost index funds for defensive investors

- He cautions against “buy what you know,” urging thorough research and avoiding familiarity bias.

- For defensive investors, dollar-cost averaging and broad diversification can create a “permanent autopilot portfolio” with steady returns.