The Intelligent Investor

Part 4: The Defensive Investor: Portfolio Allocation

Words: 1,932 Time: 8 Minutes

“The defensive investor should be satisfied with the gains shown on half his portfolio in a rising market, while in a severe decline he may derive much solace from reflecting how much better off he is than many of his more venturesome friends”

– Benjamin Graham

💥 Why This Matters

- Investor Risk Tolerance: The fundamental characteristics of an investment portfolio are primarily determined by the investor’s financial situation and risk tolerance.

- Risk and Return: The expected rate of return on an investment should be commensurate with the level of risk the investor is willing to assume

- Bond-Stock Allocation: A balanced portfolio should include both high-grade bonds and common stocks. The ideal allocation between the two depends on the investor’s risk tolerance and market conditions.

💸 Risk vs Reward

(i) the investor’s financial position; and

(ii) their risk tolerance

For instance, consider my 20-year-old niece.

She is in a position to take greater risks because she owns the most precious asset there is: time.

With decades ahead, she can afford the possibility of (many) short-term losses for the potential of higher long-term gains.

On the other hand, institutions such as savings banks, life insurance companies, and legal trust funds are generally risk-averse.

These entities are often legally restricted to low-risk investments, such as high-grade bonds or stocks in the S&P 500.

Therefore, their mandate is capital preservation, where an annual return of ~6-7% might be considered both satisfactory and sustainable.

However, for investors between the ages of “45 and 65” – a more balanced approach is recommended.

For example, they might consider holding a mix of high-quality bonds combined with both growth and defensive stocks — depending on their individual risk tolerance and life stage.

The decision to balance defensive versus higher-risk assets hinges on whether an investor can afford to recover from a severe market downturn.

For example, if you don’t have the luxury of time to wait for a strategy to pay off, your risk appetite should be more cautious.

In summary, those who cannot take risks should expect lower returns.

However, those such as my 20-year old niece should be willing to take on more risk and anticipate higher returns.

This concept underscores the relationship between risk and expected return, though greater returns may still be achievable for those who invest the time and patience required.

🔨 Outsized Returns Require Outsized Work

Graham posits the desired rate of return should be determined by the amount of effort the investor is willing and capable of dedicating to their investment strategy.

This is something which resonates with me. For example, something I often say is:

And this is true not only for investing – but for most things in life.

You’re generally rewarded for the time you put in.

If you don’t have the time to diligently study financial statements and markets (something we will explore in subsequent chapters) – the wiser option is to opt for a passive strategy such as buying a low-cost Index Fund for the long-term.

Now most investors will fall into this category… as outperformance takes a lot of work and time.

If you don’t have the time – Vanguard’s VOO is a good option for the more passive investor – which boasts an average annual return of 14.7% since 2010 (commensurate with the S&P 500)

Those investors seeking both safety and convenience should expect a market based return.

However, those investors who have the time to do due diligence and actively manage their portfolios (which should not be confused with short-term trading) – they can aim for higher returns.

Again, we will explore the scope of this work (with real examples) in subsequent chapters.

🏦 The Bond-Stock Allocation Dilemma

Graham recommends that a more defensive investor’s portfolio strategy involves a balanced allocation between high-grade bonds and high-grade stocks.

For example, he recommends maintaining a range of 25% to 75% in stocks, with the corresponding balance in bonds.

At the time of writing (October 2024) – for me personally – with the market trading ~22x forward earnings – I’m 65% high-quality stocks; and 35% across both shorter-term bonds (e.g., no longer than 3 years); and money market accounts (which yield~4.3%).

While Graham suggests a 50-50 split is a solid starting point – he adds that adjustments should be made based on market conditions. For example:

- Increasing the allocation to stocks during a protracted bear market when prices are perceived as undervalued is considered prudent.

- Conversely, reducing the stock component is advisable when the market is deemed to be overvalued.

- Adhering to these guidelines can be challenging due to human nature’s tendency to succumb to the excesses of bull and bear markets.

- Selling stocks during market rallies and buying during declines is counterintuitive for most investors.

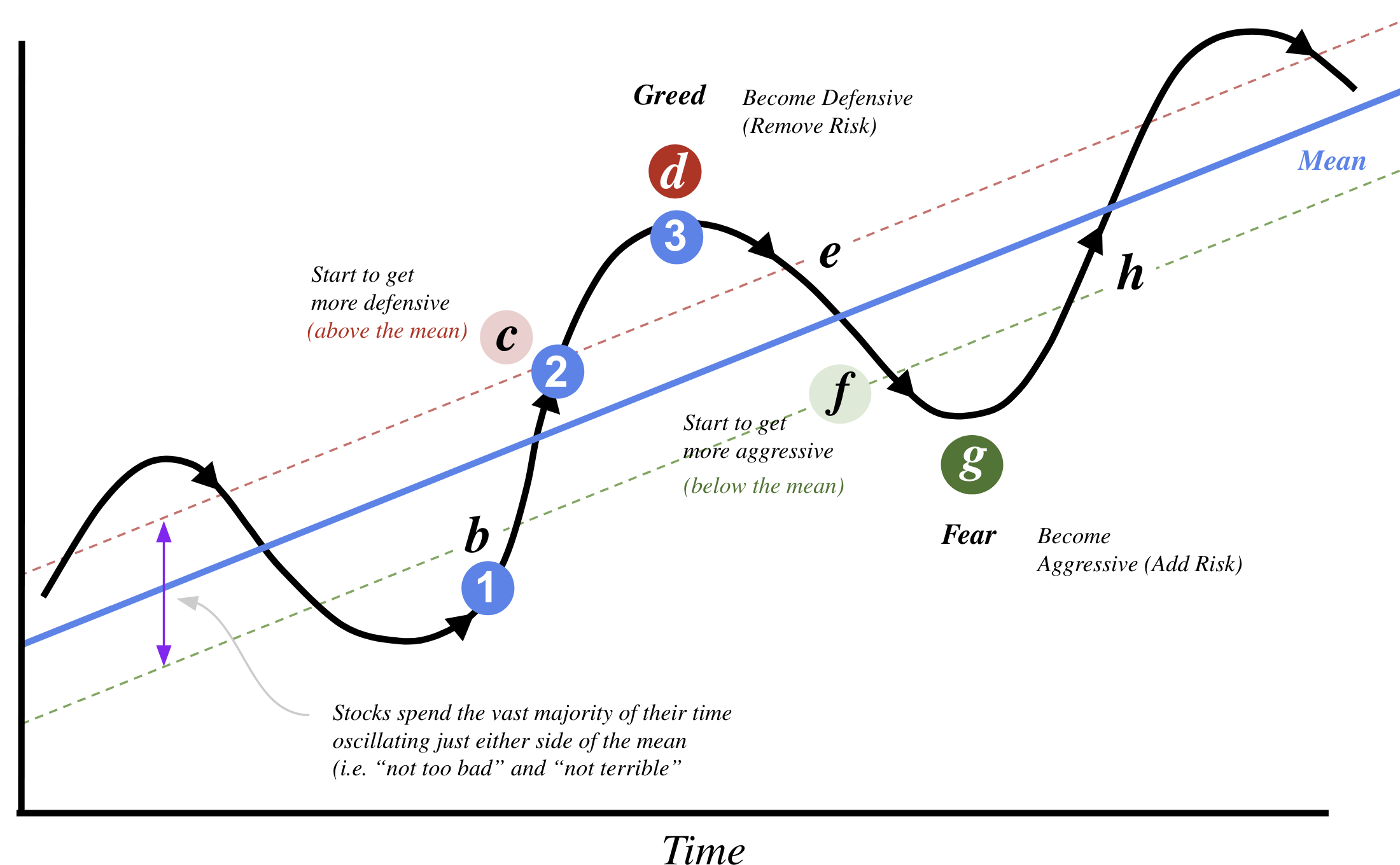

Again, we are reminded of Howard Marks’ market cycle – shared with the previous lesson

This behavioral bias often contributes to the significant market fluctuations (i.e., the extremities in our cycle)

Graham adds that if the distinction between investing and trading (or speculation) were “clear-cut” – we could envision all investors as shrewd operators selling to less discerning speculators at market peaks (i.e., selling when others are greedy); and buying back at troughs (i.e., being greedy when others are fearful).

But that’s not what happens… most investors tend to do the opposite.

Given the apparent disconnect between stock market valuations and historical norms, providing definitive rules for adjusting stock holdings within the recommended range is challenging.

His recommendation is as follows:

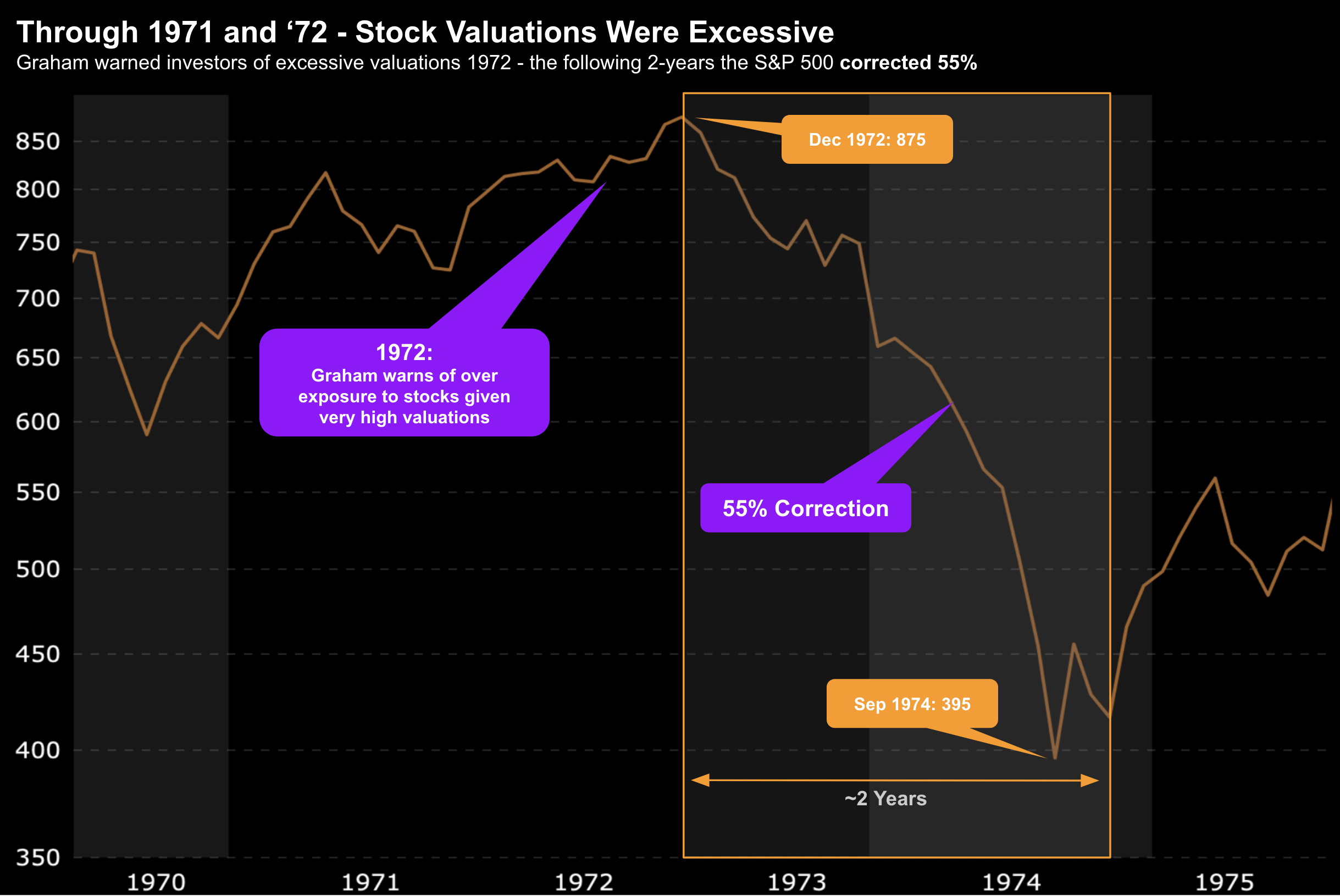

When Graham wrote the forth (and final) version of his book in 1972 – he warned about a high allocation to stocks given elevated valuations (where forward PE’s exceeded 20).

However, he added that timing is very difficult to predict — suggesting that whilst markets are considered fully valued – gains could extend further.

As it turned out – his timing was reasonably good – with a severe 55% correction to follow over the next 2 years.

🌦️ Simplified 50/50 Approach

For most investors, a straightforward 50-50 allocation between bonds and stocks may be the most practical approach.

However, Graham said this strategy is not completely passive.

For example, it does involve periodically rebalancing the portfolio to maintain the desired 50/50 allocation (e.g., every quarter or six months).

For example, if the stock component rises to 55% (e.g. due to rising prices) – selling a portion of the stocks and reinvesting the proceeds in bonds can restore the balance.

Conversely, if the stock allocation falls to 45%, buying additional stocks using a portion of the bond holdings can rebalance the portfolio.

Graham mentions that Yale University followed a similar approach for several years; it eventually abandoned its fixed allocation strategy in favor of a more equity-focused portfolio – taking on more risk.

This illustrates the challenges of adhering to a mechanical approach in the face of prolonged market uptrends.

In prolonged bull markets situations, investors will often feel they are ‘missing out’ on gains.

However, Graham feels the 50/50 portfolio provides a sense of control, limits excessive exposure to equities – giving the defensive investor a balanced approach to risk and return.

As an aside, today it’s more common to adopt a 60/40 balance to markets (60% high-quality stock or the Index; and 40% high quality bonds)

To go deeper – Vanguard explains how you can implement this popular strategy.

💲 The Bond Component

Graham talks to the multiple pathways for bond investing.

For example, options which vary in the length of bond duration; government and corporate debt; relative levels of quality; to bond options which can be tax free.

As an aside, I provided this overview of 4 popular ways to buy bonds – which touches on these pathways.

When selecting bonds for a portfolio, investors should consider three key factors:

- taxable vs tax free

- maturity profile (longer-term bonds carry more duration risk)’

- relative quality of the debt instrument (where higher quality equals a lower (safer) return

With respect to the first point, the tax decision depends on the investor’s tax bracket and the yield difference between taxable and tax-free bonds.

For example, as at October 24 2024, the taxable US 10-year bond yields about 4.20%

By contrast, the yield on tax-free municipal bonds varies by rating and maturity, as shown in the following table:

- AAA rated: 10-year yield is 2.80%, 20-year yield is 3.40%, and 30-year yield is 3.70%

- AA rated: 10-year yield is 2.90%, 20-year yield is 3.60%, and 30-year yield is 3.90%

- A rated: 10-year yield is 3.15%, 20-year yield is 3.80%, and 30-year yield is 4.15

For example, for someone like me with an income tax rate close to ~50% – the AAA tax free 10-year at 2.80% is a better deal than a taxable standard 10-year at 4.10% (which would net ~2.05% after tax)

The second factor considers the importance of striking the right balance between price stability and yield.

For example, shorter-term bonds (those less than 3 years in duration) are less affected by interest rate changes but offer lower yields.

By contrast, longer-term bonds will generally provide the investor higher yields (assuming a positively shaped yield curve) – are more sensitive to rate fluctuations.

As an aside, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank is a great example; where their long duration bond portfolio was poorly managed – over exposed to the risk of interest rates moving higher – causing the market value of their bond holdings to plummet (go deeper)

For me, as at October 2024, I favor bonds no longer than 3-years in duration – as I believe yields could rise sharply over the next few years (not necessarily in the next 12 months) – due to greater fiscal recklessness.

If this proves true (and it may not) – this will hurt long-term bond investors (as bond prices trade inversely to yields; i.e., if yields rise the value of the bond falls)

Finally, corporate bonds generally provide higher yields than government – but come with additional credit risk.

Higher-yield corporate bonds (“junk bonds”) – while offering more returns (~8% today) carry greater risks again.

The rule is simple: the greater the return – the higher the risk.

Other options include savings deposits for safety and liquidity, convertible bonds for capital appreciation potential, and bonds with call provisions, which can limit price gains.

5 Key Takeaways

5 Key Takeaways

- The aggressiveness of your portfolio (defined as the ratio of stocks to bonds) depends on your individual profile and attitude towards risk – rather than just your investments.

- Active investors invest time and effort into researching and managing their portfolios, while passive investors prefer a low-maintenance, stable strategy with minimal involvement. Both approaches can be successful, but self-awareness and discipline are key to choosing and sticking with the right one.

- Portfolio decisions shouldn’t be based solely on age, as conventional wisdom suggests. Instead, he advises focusing on life circumstances, such as your financial goals, risk tolerance, and the unpredictability of life events.

- While stocks can offer growth, bonds provide a safety net during market downturns. Graham recommends keeping at least 25% of your portfolio in bonds to reduce risk and manage emotions during volatile markets. The key to long-term success is rebalancing your portfolio regularly and maintaining a disciplined approach, regardless of market conditions.

- The key to long-term success is rebalancing your portfolio regularly and maintaining a disciplined approach, regardless of market conditions.