- When the tide goes out – you get to see who was swimming naked

- SVB was more to due to poor risk management vs Fed raising rates

- A great opportunity to buy quality banks (BAC and WFC)

When rates move higher by ~450 basis points (4.50%) in the space of twelve months… “something” was going to happen.

We just didn’t know what that something was…

This week we got a hint.

America’s 16th largest bank – Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) – went belly up.

Here’s CNN:

Silicon Valley Bank collapsed Friday morning after a stunning 48 hours in which a bank run and a capital crisis led to the second-largest failure of a financial institution in US history.

California regulators closed down the tech lender and put it under the control of the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The FDIC is acting as a receiver, which typically means it will liquidate the bank’s assets to pay back its customers, including depositors and creditors.

Obviously the news sent shockwaves through the market… sending all banking stocks sharply lower.

I watched my shares in Bank of America and Wells Fargo plunge lower… not much fun!

In fact, my entire portfolio shed ~1% this week (but far better than the S&P 500)

But tonight, let’s talk more about why I think this bank’s problems are limited to SVB… and why they failed.

In short, this was a good old fashioned bank run resulting in an effective margin call.

Sadly for SVB’s customers and depositors – risk management 101 would have seen them fight another day.

Call it a case of far too much risk balanced by far too little capital on hand.

But nothing we have not seen a thousand times before.

Easy Financial Conditions

Up until this week – the broader financial system has been largely void of any disasters.

Yes, granted we have seen blow-ups and destruction in ultra speculative rubbish (like crypto) but that does not count.

That’s expected.

Pain was always coming opposite ridiculous valuations. No sympathy there.

Now I’m sure to the Fed’s chagrin – the absence of any financial pain has been very easy financial conditions.

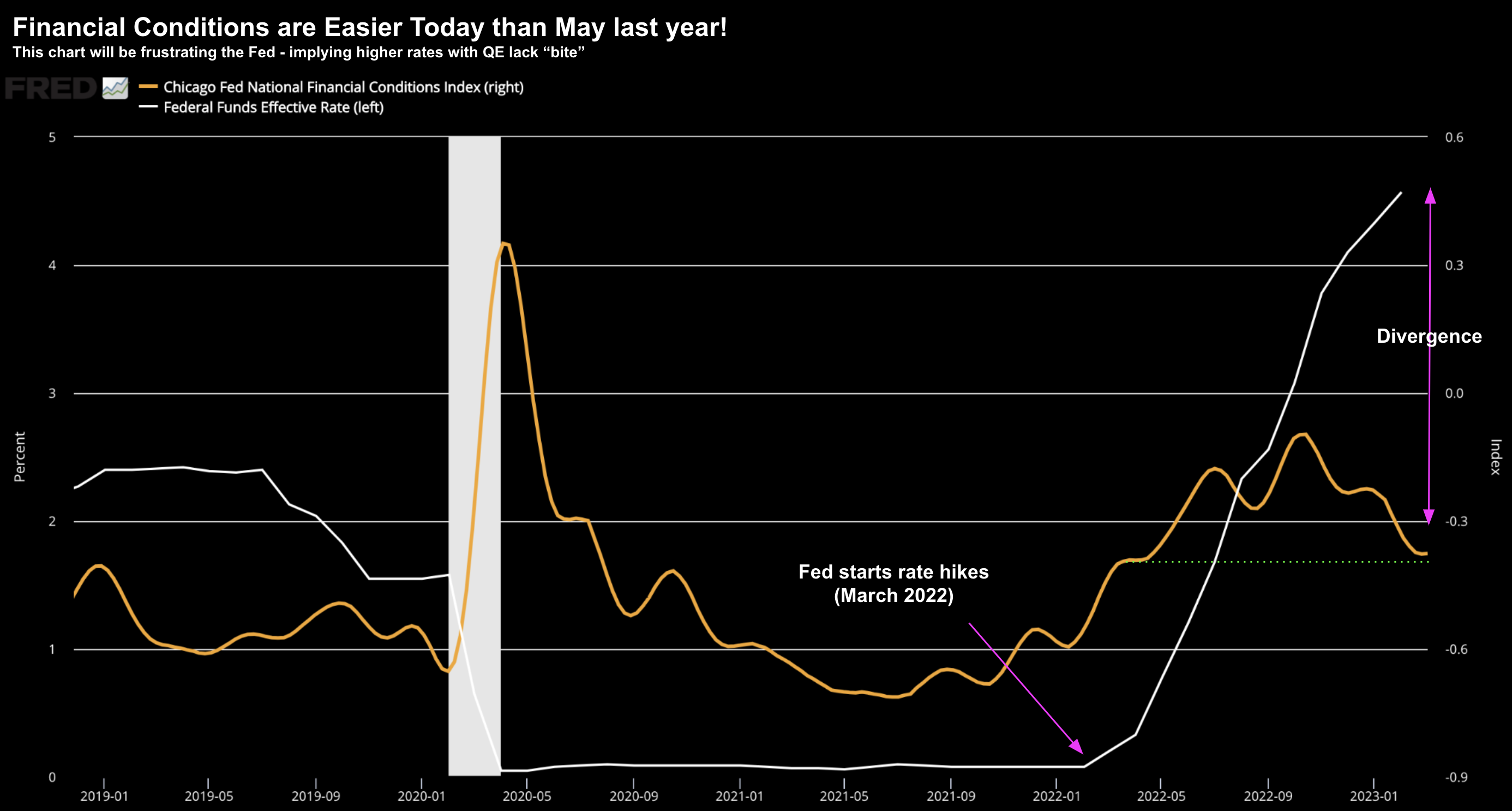

In fact, a little too easy of late – as this chart shows:

March 10 2023

The white line (left-hand axis) illustrates how the Fed hiked rates by 4.50% in just 12 months

And yet what do we find with financial conditions (orange line)?

Strangely they are as “easy” as they were 12 months ago.

Why?

The answer to this question is at the heart of the SVB collapse.

But more on that in a moment.

When we look at this chart – from September 2022 – this must be frustrating for the Fed trying to take excess money out of the economy.

Despite doing all they can to reduce liquidity (raising rates with QE) – it was having little impact.

SVB helps us to understand why… it’s all to do with accounting methods (and risk)

What Happened Here?

So how does a small-ish bank valued at $18B four weeks ago suddenly go broke overnight?

Well… gradually at first and then all of a sudden!

(Hemingway first penned that phrase – I’m not that clever)

Let’s start by describing who they are and their customer base (and you will soon connect the dots)

SVB was (not is) a niche bank in Silicon Valley lending primarily to startups and VC’s in the tech and biotech space.

Not surprisingly, in the era of free money, they scaled 4x over the past 5 years.

Amazing what free money does isn’t it?

Almost as fast the Fed made it available – SVB were taking it and lending it.

They claimed that more than half their lending book was to tech startups.

Clearly no risks there!

Given we know that 90% of all startups fail – it’s fine when they are going well – but not so great when things turn the other way.

And terrible when they start need to withdraw funds.

This week SVB faced something similar to a margin call.

That is, they need to either (a) inject more cash (which they didn’t have); or (b) sell assets.

They were forced to do (b)

But there was a problem…

As more depositors wanted their money out – this required SVB to come up with the cash.

They didn’t have enough cash on hand so they were forced to sell assets – which were treasury bonds.

Now US treasuries are generally a very safe asset to hold through to maturity.

But…

Problems can arise if you are forced to sell prior.

As we know, over the past 12 months, treasury yields have ripped higher which has seen bond values plummet.

March 10 2023

SVB Financial’s shares were hit hard on Thursday after it announced it had sold around $21 billion worth of securities from its portfolio at a loss of $1.8 billion.

The company also announced it is seeking to raise around $2.25 billion by selling a combination of common and preferred stock.

The company said it was undertaking these steps as challenging market conditions and high cash burn among its clients led to “lower deposits than forecasted.”

Shares of other major financial institutions and the overall market were also hit by the selloff with the four biggest U.S. banks losing more than $52 billion from their valuation.

Leading VCs compounded the situation by advising their closely knit community to get their money out asap (e.g. such as famed VC Peter Thiel and others)

Here’s the thing:

The rapid withdrawal of cash meant SVB did not have the luxury of holding their bonds to maturity.

With more depositors asking for return of their money (e.g. as they could put it in risk free 6-month treasuries for say 5%) – it forced SVB to take losses on their ‘safe’ bond investments.

But all of this could have been easily avoided…

Why They Failed

As a preface, you are probably going to read a lot of reports saying “this is all the Fed’s doing… they went too far and this is the consequence”

I disagree wholeheartedly.

The Fed have been extremely transparent on their intention to raise rates to fight inflation the past 12 months — however SVB refused to take the necessary steps to hedge their risk.

Further to my preface, this was a case of far too much risk balanced by far too little capital on hand.

Now a major part of the problem is Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) practice does not require firms to mark down their (bond) assets to market value.

That’s a problem… especially if they are not held to maturity.

The Fed knew this was an issue… particularly with regional banks.

For example, I am sure the central bank were probably saying something like:

“Hey Regional Bank ABC – you need to manage your risk. Your mark-to-market issues are now becoming a problem and you need to get inline. In others words, you need to tighten lending conditions (i.e. mark them to market)”

This come back to the chart I shared in my preface… and helps explain why financial conditions continued to show easing (despite the central bank tightening rates)

Banks like SVB didn’t tighten conditions – despite their lower capital base.

Put another way, if banks marked their bonds to market – it would have the effect of reducing availabile liquidity.

That’s what the Fed wanted (or expected) to happen.

Now larger banks know this…

Banks such as (not limited to) Bank of America and JP Morgan have navigated waters like this many times in the past.

Bigger banks will implement hedging for specifically these kind of scenarios.

They are also acutely aware of their liabilities.

Can we say the same thing for all regional banks like SVB?

I am sure some stringently manage their risk… but clearly not all.

From mine, their collapse is not unlike the bankruptcy of Savings and Loan of the 1980s (absent the fraud)

The problem began during the era’s volatile interest rate climate, stagflation, and slow growth of the 1970s and ended with a total cost of $160 billion; $132 billion of which was borne by taxpayers.

Key to the S&L crisis was a mismatch of regulations to market conditions, speculation, moral hazard brought about by the combination of taxpayer guarantees along with deregulation, as well as outright corruption and fraud, and the implementation of greatly slackened and broadened lending standards that led desperate banks to take far too much risk balanced by far too little capital on hand.

Putting it All Together

This is what you might call “tail risk” in the system (not core).

Yes, this is the largest banking failure since Washington Mutual (2008)

And it’s noteworthy.

They funded 50% of all American startups. That’s a lot of innovation now without cash flow to cover payroll Monday morning.

This will impact tens of thousands of innocent (tech) workers.

And that’s who I feel bad for… this was not their fault.

I have no sympathy for the equity and bond holders of SVB. This was gross mismanagement.

If I were to guess – it’s not going to be the last company filing for bankruptcy this year.

But it’s not something to be concerned about for the broader banking sector.

America’s largest banks – Bank of America, JP Morgan, Wells Fargo etc – are in very good shape.

In fact, I used today to add to my positions in BAC and WFC.

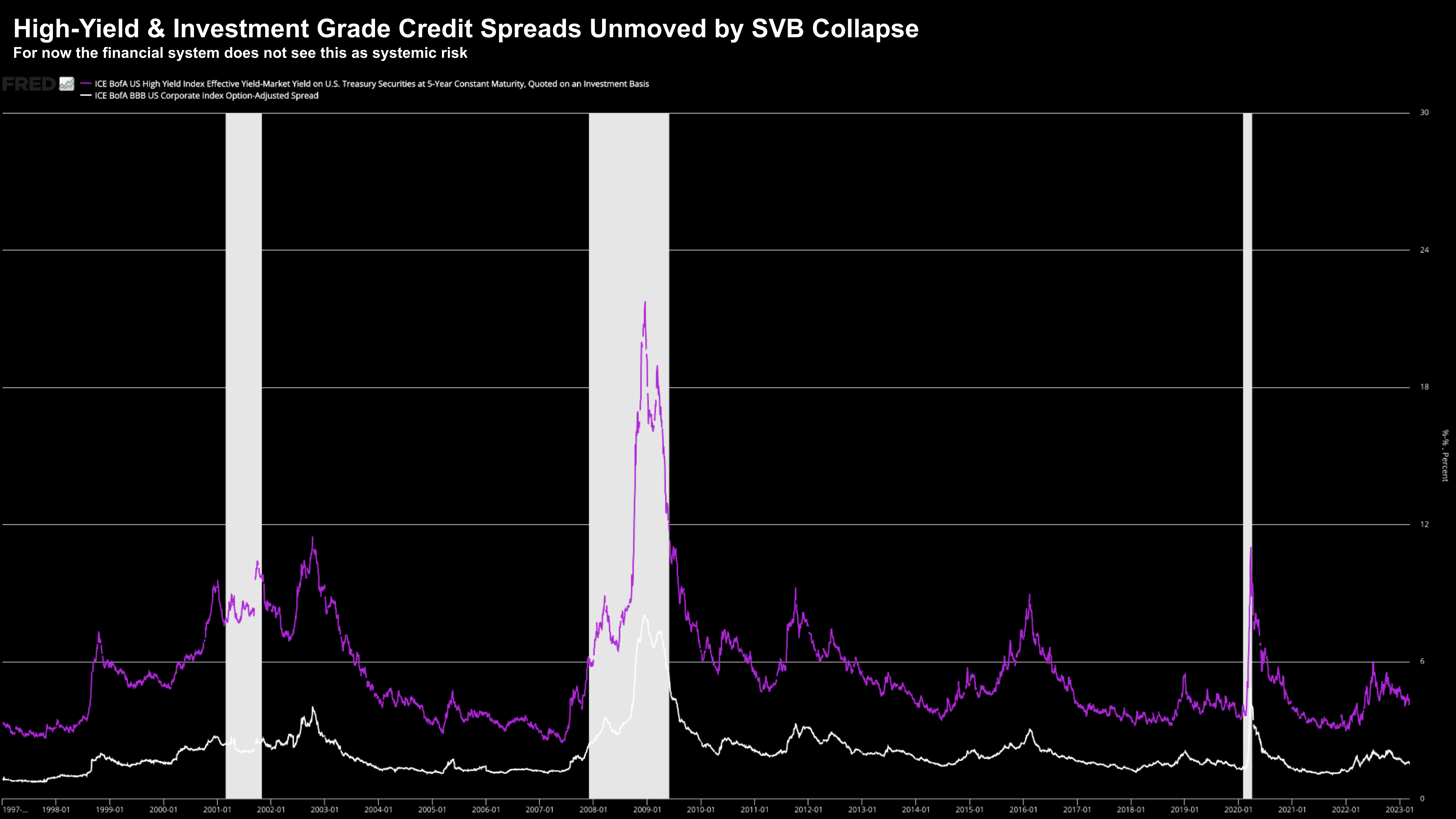

So here’s your real tell if there is a widespread (systemic) problem…

Look no further than credit spreads.

March 10 2023

If I saw these spreads shoot sharply higher — I would be raising an alarm.

But there has been no reaction.

Could there be further collapses with other regional banks?

Absolutely!

Again, rising rates to the tune of 450 bps in 12 months won’t be without pain.

Powell said to expect it.

We just don’t know who they are yet. The tide is still making its way out.

But if assessing the risk of a regional bank – you should ask the question what their funding base is?

That’s the key.

Personally I’m not worried about this resulting in widespread financial contagion.

However, there was panic in the sector today.

I used the panic as an opportunity to add to both Bank of America (BAC) and Wells Fargo (WFC).

BAC’s valuation is as cheap as I’ve seen it in a decade.

I readily accept there will be a ton of volatility in banks over the next few months.

That’s more than fine.

And the banking stocks in my portfolio will probably take more of hit (e.g. perhaps 10-15% downside)

But I think over the next 3 years my bets today on BAC and WFC will look like solid entry points.

Could be wrong.