- Treasury set to issue $1.1 Trillion in short-term notes after debt deal

- Could that result in a large exodus from bank deposits (i.e., to higher yielding bonds)? and

- What a likely slower increase in government spending means for GDP

Last week I offered one explanation as to why both stocks (and the economy) are holding up better than many expected.

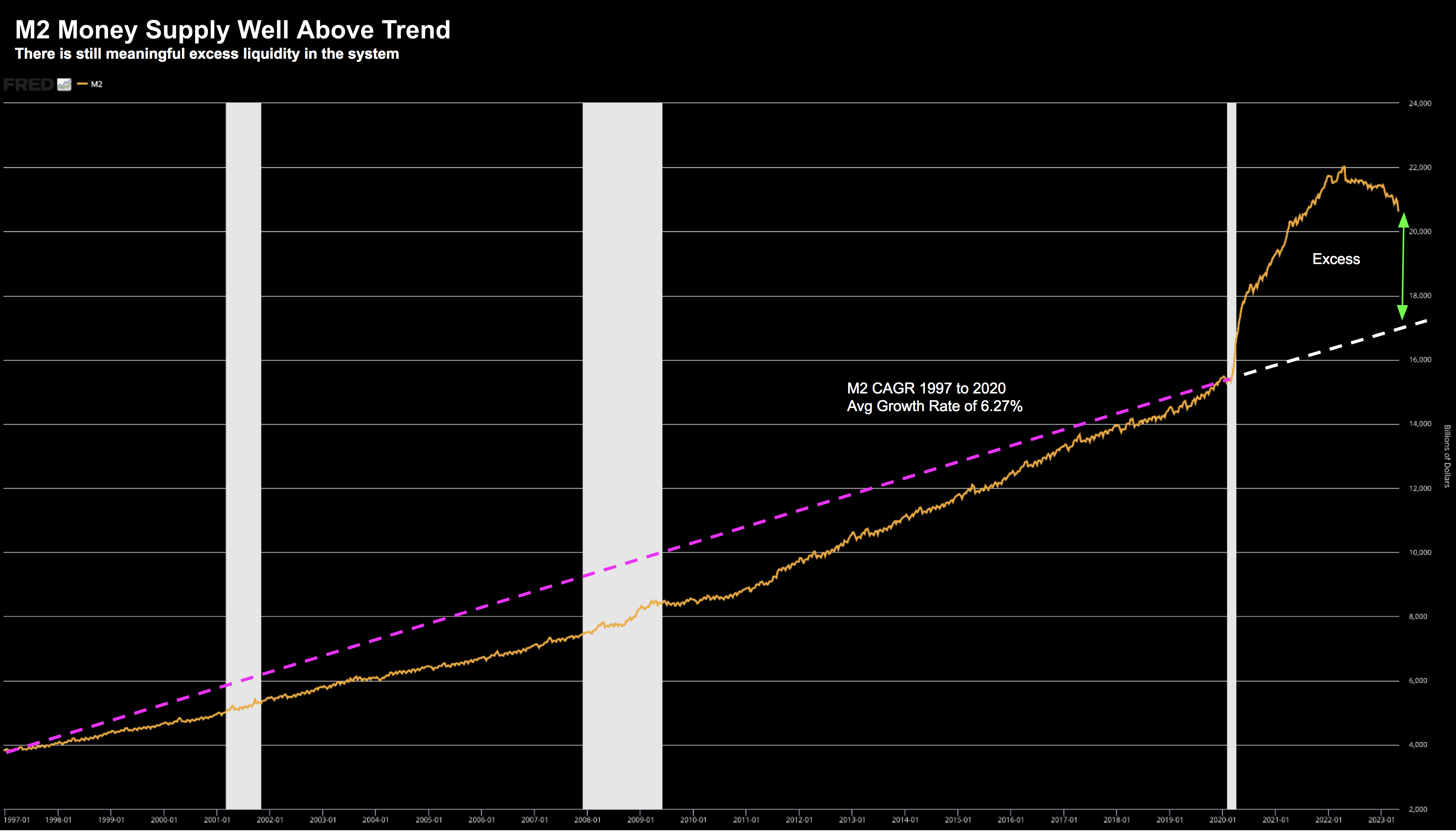

It comes back to liquidity (and money supply).

For example, there still something like $2.6 Trillion ‘surplus’ liquidity still available in the system as a result of total $6 Trillion created from COVID:

If the rate of M2 growth remained closer to its 6.2% long-term trend – the balance would be closer to $18 Trillion.

Instead this number is $20.6 Trillion

In combination with years of reckless fiscal policy (both Administrations) – this is the primary driver of inflation.

The question is what could cause this to fall?

Part of the answer may lie in the debt ceiling deal reached this weekend.

Inflation Likely to Fall

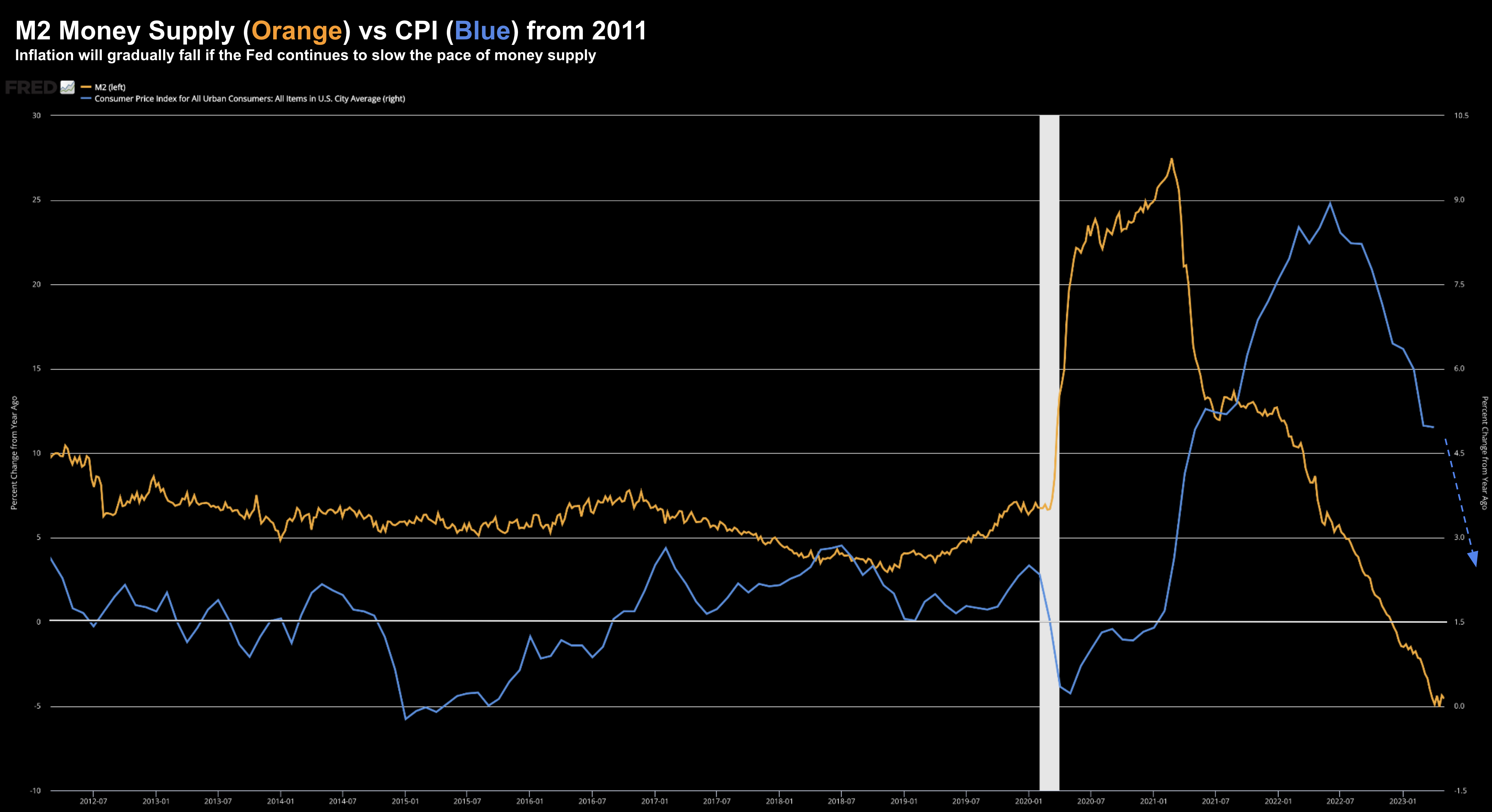

M2 money supply peaked in April 2022 at ~$22 Trillion.

Since then, the Fed has reduced the creation of money – turning negative year-on-year in recent months:

The good news (from my perspective) is this is helping to bring down the impact of inflation (with less excess money in the system)

For example, if we overlay CPI (blue) with the YoY change in M2 money supply (orange), you can visualize the lagging impact.

At a guess – we could see inflation down to a 3-handle in approx 9-12 months time.

Whilst inflation is likely to come down – it’s happening slowly.

And this is mostly a result of stickier forms of inflation (wages and rent) being more stubborn than the (sharp) fall in goods and commodity prices.

Note: Fed President Williams gave a good overview of this here.

But there might be another catalyst to help bring down inflation (in turn amplifying QT) whilst reducing liquidity…

And this could be from the fiscal side…

A Spending Cap in a Slowing Economy

Over the weekend, financial media reported a deal in principle to raise the debt ceiling.

Surprise surprise.

Based on all reports, the deal sets a two-year spending cap, kicking in at the start of the fiscal year that begins October 1.

Now pending your ideological lens – a spending cap is a good thing.

Don’t worry – at least 50% of people reading this post will disagree (and that’s fine).

But let me try and make an argument for slowing spending…

To start, it’s the result of excessive government borrowing and spending which is mostly why we have an inflation problem.

Excess money is chasing too few goods.

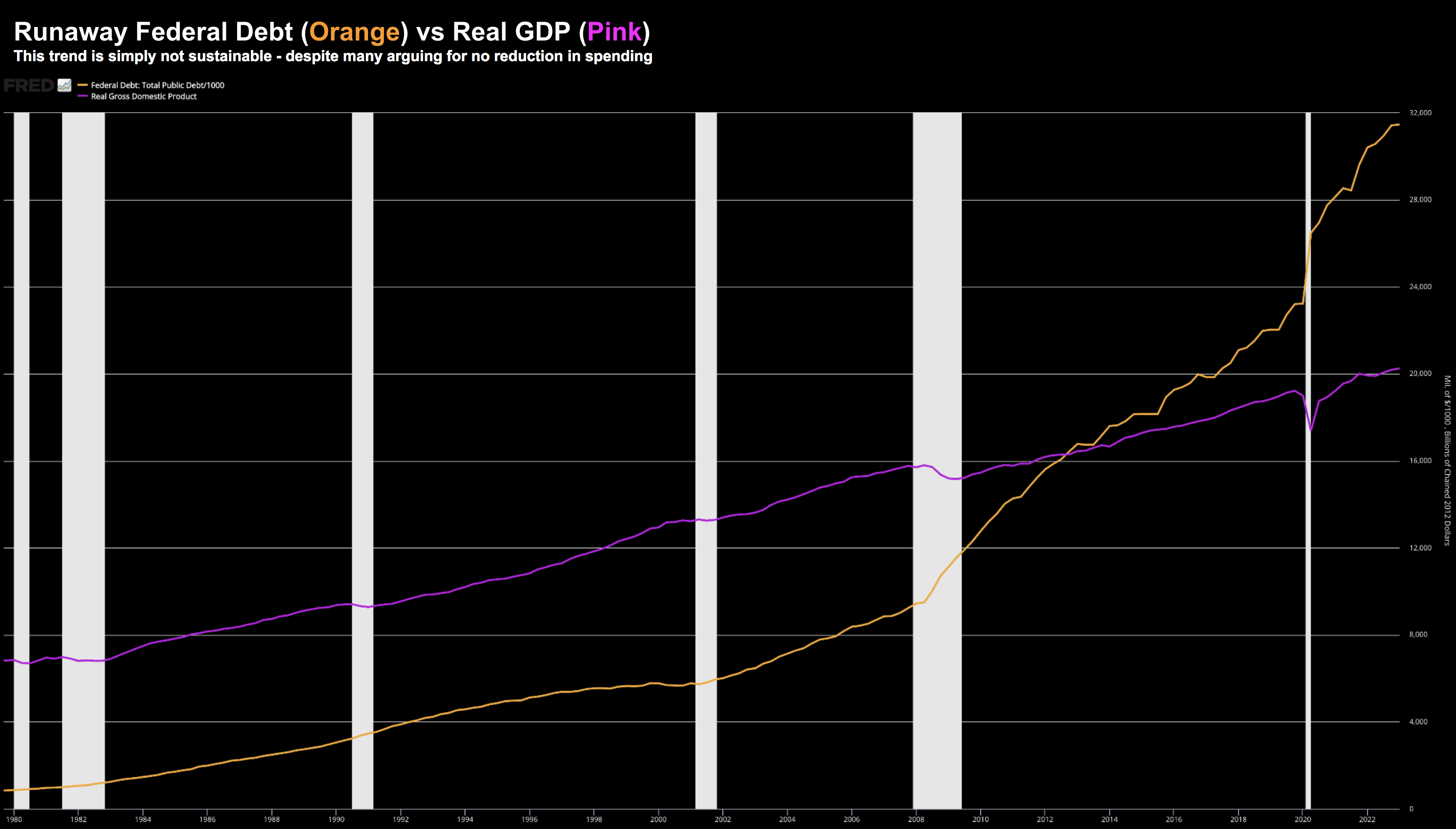

Whilst this is not the focus of this missive – the chart below helps visualize why spending needs to slow.

In short, the amount of cumulative debt (as a result of borrowing and spending — and why the debt ceiling needs raising) is rapidly outpacing what we are producing (i.e. GDP):

Two lines on the chart below show:

- Federal debt ($31.5 Trillion); vs

- Real GDP ($20.2 Trillion)

May 29 2023

Again, whilst your political and ideological lens will likely differ to mine, I posit this (spending) trend is simply not sustainable.

Note – spending “cuts” is the wrong language.

A cut implies that spending will fall year on year. That will not be the case. Spending will still rise as a result of this negotiated deal – however it will increase at a slower rate. This is often miscommunicated in financial media.

Now if Washington DC agrees to at least slow its spending – they’re likely to be doing it during an economic slowdown.

And this could have a near-term impact on economic growth and the valuations of risk assets.

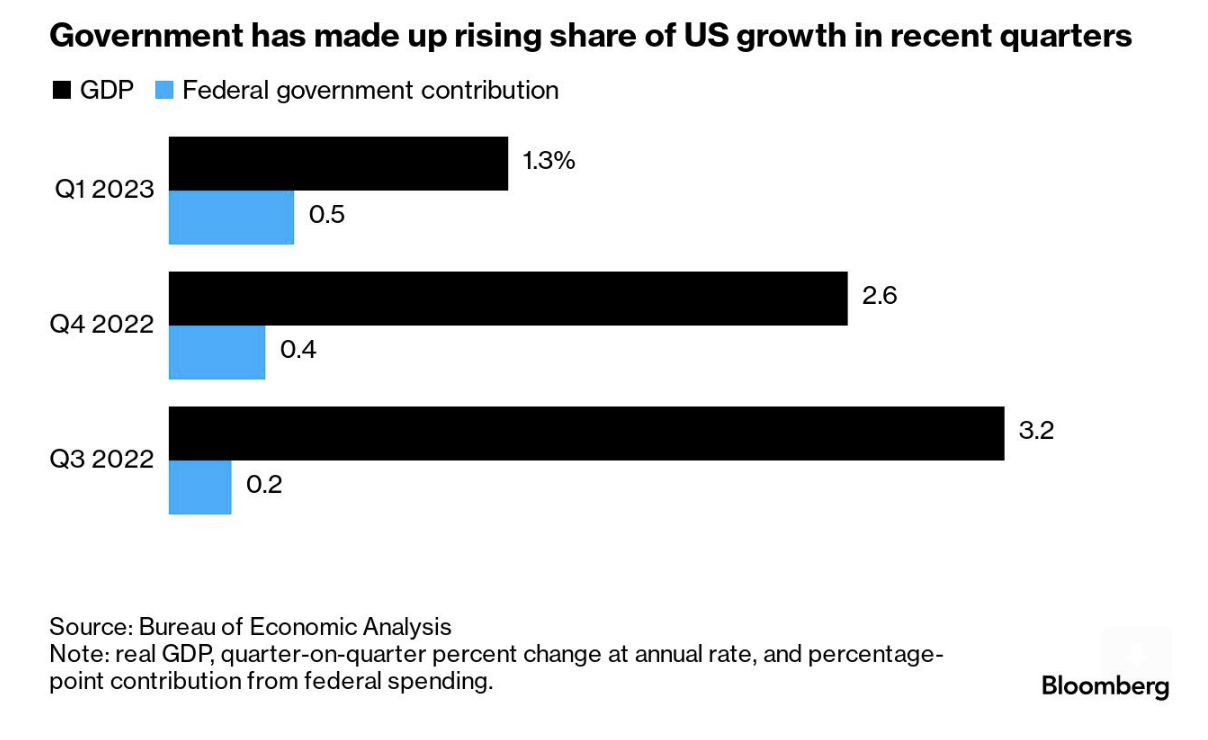

Michael Feroli, chief US economist at JPMorgan, believes that reduced government spending tends to have a multiplier effect during a recession.

From Bloomberg:

“Fiscal multipliers tend to be higher in a recession, so if we were to enter a downturn, then the reduced fiscal spending could have a larger impact on GDP and employment”

I agree.

Here we see how the ‘government credit card‘ has been helping reduce the “GDP gap” — constituting a whopping 0.5% of GDP last quarter (more than 30%).

In Q3 2022 it was only 0.2% of the total 3.2%

And given I think we’re most unlikely to avoid a recession (based on a host of leading indicators) – a pullback in fiscal spending will likely see GDP contract further.

I could be wrong.

But let’s talk to the (less obvious) impact on liquidity as a result of any deal.

This is likely to have a more immediate impact on equities (further to my recent posts).

The Potential Impact on Liquidity

Perhaps the less discussed impact of any debt ceiling deal will be the near-term impact on liquidity.

For example, we know the government will likely run out of money within ‘weeks’.

I believe the latest estimate is June 5th (but reality is it’s likely to be further out).

In any case, this month the US Treasury will need to go to market with $1.1 Trillion in fresh t-bills (likely staggered over several months) as soon as the deal is passed.

And this will have the Fed’s attention.

For example, as the Treasury ramps sales of new debt – this will effectively remove cash from the financial system.

Now pending how the Treasury issues these short-term bills – this could amplify the Fed’s QT.

From a market perspective, the question will be how this impacts credit.

Let me explain….

For example, today the government will likely issue bonds at rates of around 5.0% (or higher).

In turn, it’s possible this will also deplete banks’ reserves.

This happens because deposits held by private companies (and others) move money to higher paying and relatively more secure / risk-free rates.

In theory, this could add to deposit outflows, putting more pressure on liquidity available to banks.

From there, this may also have the impact of driving up rates charged on near-term loans and bonds — making funding more expensive for those requiring access to credit.

BNP estimates that we could see some $750 billion to $800 billion move out of cash-like instruments (e.g., bank deposits) and into higher-yielding T-bills.

And that’s what the Fed will be watching.

Mike Wilson, Chief Equity Strategist at Morgan Stanley who is bearish on stock market valuations, sees this happening.

He says that Treasury bills issuance will:

“… effectively suck a bunch of liquidity out of the marketplace, and may serve as the catalyst for the correction we have been forecasting”

Again, it’s very hard to predict exactly how much liquidity the issuance of T-bills will see.

For example, the T-bill issuance could be partly absorbed by money market mutual funds, shifting away from the overnight reverse repo facility, where market players lend overnight cash to the Fed in exchange for Treasuries.

That would be a better outcome for equities as liquidity will be less impacted.

However, if we are to see something like a “$700B+” shift from bank reserves to t-bills – that will cause more uncertainty in the market (and higher rates).

Putting it All Together

In the very short term – news of a debt ceiling deal will be well received.

The media will exhale knowing the US will not default.

Crisis averted they will say…

But as I said yesterday – a default was never going to happen.

From a market and investing perspective, there are two things worth watching:

- The impact on GDP when the government slows (not cuts) its rate of spending; and

- Whether the issuance of $1.1 Trillion in short-term T-Bills acts as a liquidity suck?

I think the former is a given… given how the government is propping up GDP via its credit card.

And as we know, that trend is simply not sustainable.

However, what’s more difficult to predict is the latter.

For example, will we see a meaningful shift from bank deposits to higher yielding short-term bills?

I think that’s likely… especially given the risks with equities (and high valuations) in the near-term.

Or will this be partly absorbed by money market mutual funds as they effectively rotate funds (likely to have a lower impact)?

I don’t know the answer but it’s something the Fed will need to watch closely.

What I do know is liquidity is the market’s oxygen. It’s the only thing propping things up.

If you take it away – then the patient will gasp for more air.