- The only way to win at asset speculation

- Are you a good or bad investor (and how to know)?

- A sound intellectual framework

With the S&P 500 near record highs… some investors are wondering whether they should take profits.

And if taking profits – what stocks do you sell?

Selling is one of the hardest things to do in the game of asset speculation.

On the other hand, buying an asset is generally the easy part.

When investors are faced with meaningful profits (or losses) – deciding to sell is hard.

With respect to crystallizing a loss – for many investors – this can be especially painful. It means admitting things did not turn out the way you expected.

But that’s part of the game… not every horse we back will be winner.

That said, there should be framework in place when deciding to sell an asset. From there, the process is straight forward.

I will discuss more on how I do this below…

Beforehand, there is an important question every investor should always ask.

And from mine, it differentiates those who are likely to succeed (vs those who don’t).

Only One Way to Win at this Game

Do you consider yourself a “good” or “bad” investor?

For example, one might say a good investor is someone who beats the returns of the Index over a long period (10.5% annualized)

Beating the Index over the long-run is difficult to do… very few fund managers are able to do it.

But to help you answer – think about it this way:

- Bad investors think of ways to make money;

- Good investors think of ways not to lose money.

Does that change your answer?

Think of your last 10 investment decisions. What was your thought process?

Was it:

(a) how much could this trade make if I’m correct? or

(b) what are the risks to my portfolio if I’m incorrect?

Of the several thousand posts I’ve written the past 13+ years – this is arguably the most important question you could ask.

If you understand the gravity of this distinction… you have a good chance of succeeding.

A bad investor will end up giving back the money they earned to the market. Over time, their wealth will be transferred to the good investor.

On the other hand, a good investor will typically keep much of what they make. They rarely give the money back.

And whilst this sounds like common sense… in my experience few investors frame their investment decisions this way.

They approach investments from one dimension; i.e., how much can I make?

For example, it goes without saying that most people are interested in not only making lots of money – but they want it sooner rather than later.

However, what they don’t understand is by compressing your timeframes (e.g. in terms of days, weeks or months) – you exponentially increase your chance of loss.

Put another way, the longer your timeframe, the greater the chance of success.

Consider this….

Log into YouTube, TikTok, Insta or Twitter… and you will find any number of “money making” experts.

Not only do they promise a road to riches… they can do it in rapid time with very little knowledge needed.

What could possibly go wrong?

A search for ‘successful stock trading’ on YouTube yielded the following (and this list is not meant to be exhaustive):

- “How to Invest in 2024 – The BEST Way to Get Rich” – 288K views

- “7 Things I Learned from Making $15M as a Day Trader” – 889K views

- “Beginners Guide to Day Trading (with ZERO experience)” – 649K views

- “My Morning Trading Routine for a Quick $400/Day” – 301K views

- “This Never Fails Me – How I Make a Living Day Trading this ONE Simple Strategy” – 425K views

- “$8,000 in 7 Days” – 289K views

From mine, the millions viewing this click-bait is illustrative of today’s “investing” zeitgeist. It’s the stock market casino.

But consider the titles you don’t see:

- ‘The most effective way not to lose money’;

- ‘How to better quantify your downside risk’;

- ‘What you could stand to lose with your next trade?”

Bad investors dont think to ask these questions – they only think of the possible (fast) upside. Good investors think about it from the other way.

And from mine, this is the reason that most investors fail.

Bad investors are often swept along with the crowd (largely in part to mainstream media) – lacking a clear disciplined framework for making investing decisions.

Put another way, they don’t clearly understand the risks they’re taking. Call it a form of finanial (risk) illiteracy.

To be clear, this is not to say that people attempting to make money are necessarily “greedy”; or not smart enough to understand speculation.

Not at all…

It’s more they are less literate when it comes to understanding risk.

The ‘millions’ of investing or trading ideas we see on social media platforms clearly have a large Main Street appeal (it’s why these people tweet!)

The only problem is – most don’t work over the long-term.

Not only is this is a large disconnect… it’s also to Wall Street’s advantage.

Investing Isn’t Supposed to be Vegas

People who enjoy this type of click-bait would be wise to unsubscribe from my blog.

What I do is incredibly boring.

The content I produce does not make for compelling YouTube videos or Twitter headlines.

Then again, I am not doing this for “likes”.

And perhaps to Wall Street’s chagrin – my investment approach is not to their advantage:

- First, I only choose to take risk when the probabilities are heavily in my favour (i.e., upside gains handsomely outweigh the downside risks); and

- Second, once I get into a position – I tend to sit for a long, long time.

It’s the polar opposite of what Wall Street want me to do.

Wall Street want me to (a) buy when markets are screaming higher (i.e. which increases the probabilities of downside); and (b) want me to churn as many trades as possible.

That’s how the ‘house’ wins.

Unfortunately for them, my average holding time is between three and four years.

It’s not three or four “days, weeks or months”. Rarely does a trade have time to bear fruit in such short time.

And there are months when I may not buy a single stock. If theres nothing compelling – I don’t buy.

That’s hardly a compelling strategt for entertaining viewing on social media.

But here’s the thing…

Rarely do I give back money.

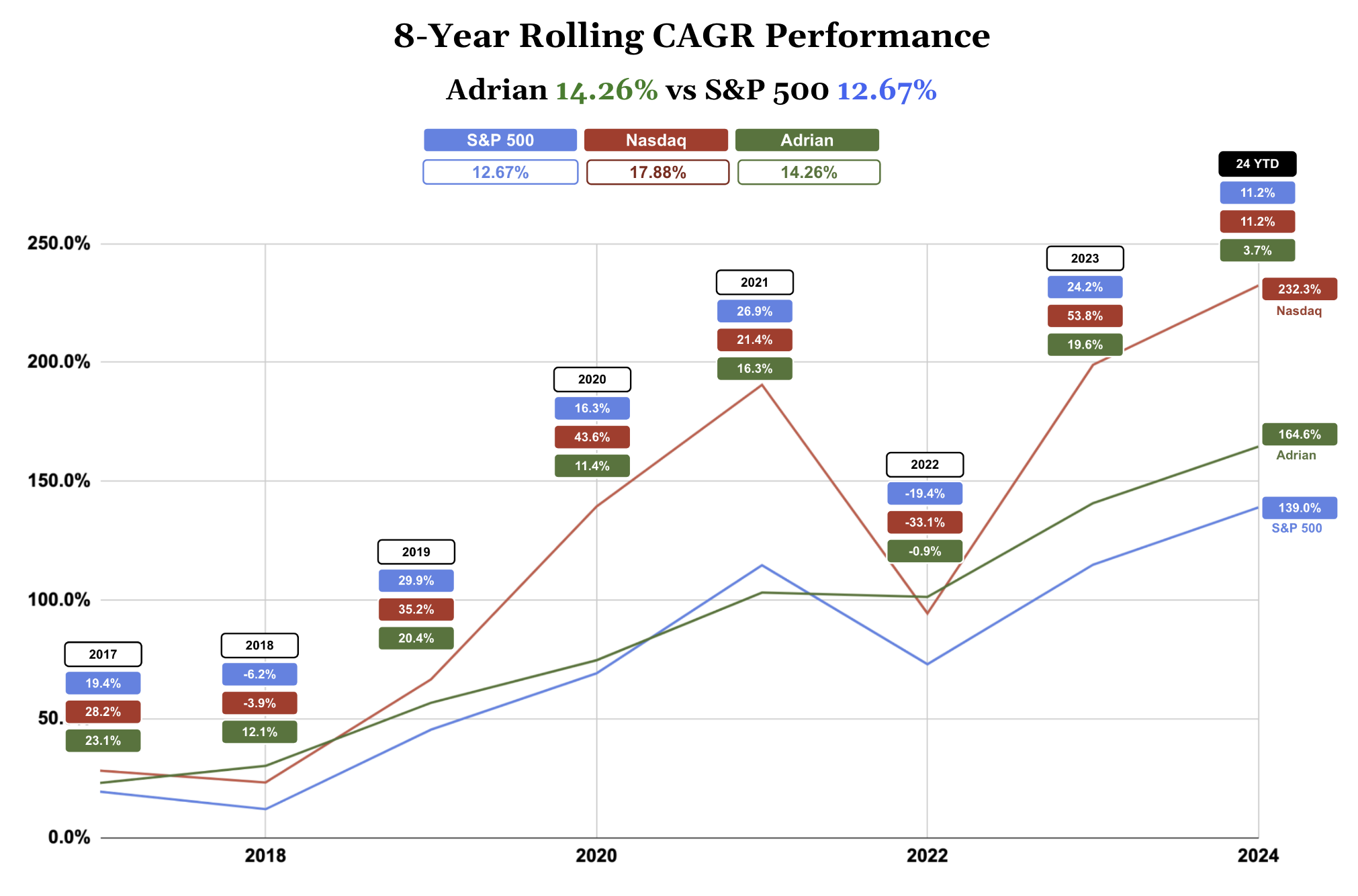

Consider this 8-year CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) chart below and specifically the drawdowns I’ve experienced

Here I compare my performance vs (i) S&P 500 (blue); and (ii) Nasdaq (red)

For every year, I plot the annual returns for (i) S&P 500 (blue); (ii) Nasdaq (red); and (iii) my own performance (green)

For example:

- 2017 – I returned 23.1% vs Nasdaq at 28.2%; and the S&P 500 19.4%

- 2018 – I returned 12.1% vs Nasdaq -3.9%; and the S&P 500 -8.2%

From 2017, my 8-year rolling CAGR is 14.3% vs S&P 500 12.7%

But what I want to draw your attention to is the year 2022….

The market suffered heavy drawdowns – with the Nasdaq drawing down some 33.1% and the S&P 19.4%

My performance in 2022 was negative 0.9%

In other words, I didn’t give back the gains I had made the previous few years.

And when conditions favoured long-term risk/reward (e.g., with the S&P 500 trading around ~3600) – I added exposure – which paved the way for a solid 2023 (returning 19.6%).

Let’s now consider the “bad” investor…

They were probably looking for (fast) ways to make money in 2022 – urging others to be bullish. Or they failed to manage their risk.

It’s one of the stock market’s timeless archetypes.

He or she is always on social media platforms – sharing ‘wisdom’ on why a stock is set to take off (or fall) – as people rush to reflexively accept the trade.

But at what risk?

That part is often ignored.

What the good investor does is invert the question of “how much could I make” to “what could I stand to lose”?

When you do this – you are at an immediate advantage.

From there, the next step is learning to understand the mechanics of the market. And this is where those ‘9-inches between your ears’ comes in.

A Sound Intellectual Framework

When I started this blog in 2011 – I wanted to help people become more financially literate.

It wasn’t just about why I thought “Apple was a good bet” or “why the Fed might cut rates” – it was more about managing risk.

I set out to help people make better decisions – avoiding problems from the beginning.

Quoting my About page:

[This blog] is written to help you make better financial decisions.

And to that end, I think author Peter Bevelin, put it best: “I don’t want to be a great problem solver. I want to avoid problems—prevent them from happening and doing it right from the beginning.”

“To invest successfully over a lifetime does not require a stratospheric IQ, unusual business insights, or inside information. What’s needed is a sound intellectual framework for making decisions and the ability to keep emotions from corroding that framework”

Bernard Baruch – who enjoyed similar success to Buffett in the first half of the 20th century – said this:

“To break free of this cycle of breakdown and build up, we must free ourselves of man’s age-old tendency to swing from one extreme to the other.

We must seek out the course of disciplined reason that avoids both dumb submission and blind revolt

“It is not mere chance that whenever society is swept by some madness reason falls as the first victim”

That’s a framework ‘good‘ investors should aspire to.

If you want to read more on how to develop this framework – here’s a list of books which have helped me.

Selling is Hard

Once we start to think more in terms of risk (i.e., focusing on what we could lose vs gain) – your framework for better decisions will start to come together.

You will start looking at investing through a very different lens.

It’s the same lens used by Wall St.

But let me say this…

Whilst choosing to take risk can be a difficult decision… selling is harder.

Let me explain…

There is no shortage of people eager to tell you why you should buy a specific stock. Tune into CNBC or Bloomberg and you will hear something like:

- “the bigger risk is simply not owning this stock”;

- “the stock is now attractively priced”;

- “earnings are set to grow more than double-digits”;

- “revenues likely to double in the next two or three years”;

- “a new product is coming”; or

- “this company will be acquired”

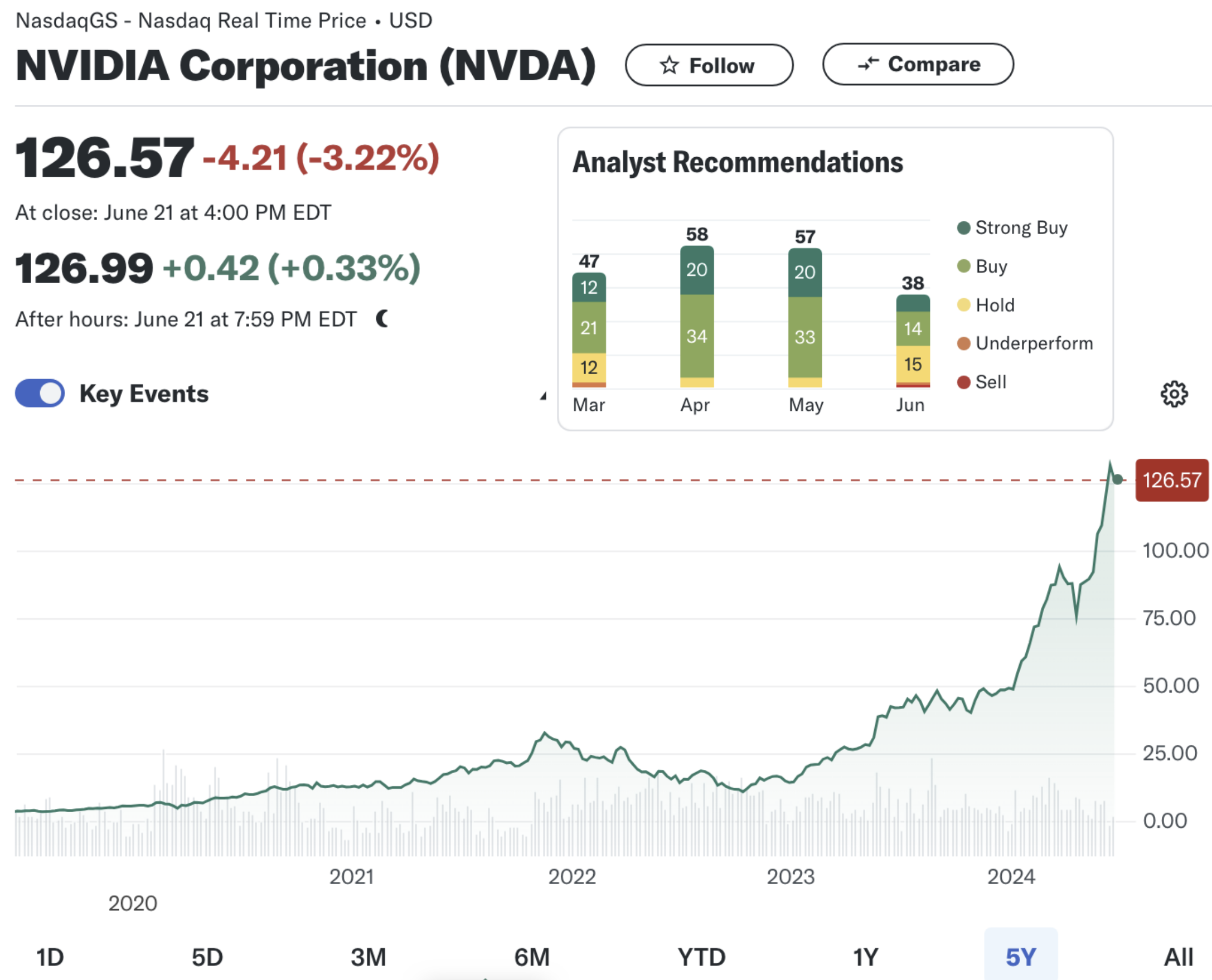

Consider market darling Nvidia (NVDA).

Of the 200+ analysts covering this stock – there is only 1 sell recommendation.

Now if we’re to channel our inner Charlie Munger – we should always look to invert what is being offered.

And what do we find?

Wall Street very rarely tells you when to sell.

And there’s a good reason for that…

If Wall Street was telling you to dump a stock – it will likely upset the various companies they tend to represent.

It comes back to financial incentives.

Many of the investment banks on Wall Street are paid by these companies for various services.

Therefore, this is why you will almost always see the number of buy recommendations far outweigh sell.

Almost “200 buys vs 1 sell” is not uncommon – especially when it comes to a “trendy” stock like NVDA.

Wall Street is far less likely to assist you with selling (but it’s eager to get you to buy)

Now part of the challenge is there is no “one size fits all” with selling a position.

Your selling discipline will most likely differ to mine… pending your own investment style and timeframes.

As I mentioned earlier, typically I will hold a stock between 3 and 4 years.

That what works best for me – as I need to give the business cycle a chance to work.

But you need to have a specific discipline.

Because if you don’t have that – then you’re simply gambling.

I see selling as risk management.

The best way to think of it is similar to insurance.

For example, late last year (and earlier this year – Feb), I sold more positions than I bought.

I was looking to reduce my exposure (very similar to what I did in early 2022)

Why?

Because it limited my downside risk (not unlike an insurance policy). I didn’t want to give money back.

To that end, I don’t view selling as trying to “time the market”.

That’s very hard to do.

I don’t pretend to call market tops or bottoms (I will leave that to the liars who pretend to).

I see it as managing my risk.

It comes back to the same question I ask myself in any position “how much could I lose?” (vs what could I gain)

Over the past 25+ years I’ve taught myself to see selling about maintaining constant touch with the market to ensure the reason I initially bought the position (my investment thesis) is still valid.

For example, does the upside reward still exceed the downside risks?

If that answer is a definitive no – then I sell.

For example, when I buy a stock, I know I’ve already decided to sell it.

But I’m not looking for a gain of 10% or 20%…

Generally I’m looking for a gain of 50% or far more. However, generally that requires patience. It’s most unlikely to happen in the quality stocks I choose to own in the space of a few weeks or months.

It requires time in the market (hence my 3 to 4 year average hold time)

And I always have a firm idea of what I think a company can get to…

Consider Apple:

A few months ago (May), I offered a thesis on why I believe the stock could trade well north of $200.

At the time, I said one of the bigger opportunities is AI on its phone, leveraging its massive install base (which I believe is Apple’s biggest advantage – their moat)

However, my thesis required a discipline of buying the stock between $150 and $165 (and not at the ~$185 it was trading for at the time)

When the stock gets closer to my objective – I review it to determine if anything consequential has changed.

My actions are not determined by day-to-day or week-to-week fluctuations. I leave that to the various talking heads on CNBC and the “YouTubers”.

It’s based on my own careful financial analysis.

This gives me the conviction to not be scared by market moves.

For example, let’s say Apple “blew up” after I took a half-position at $165. Let’s say it lost another 20% due to some perceived “regulatory risk” and traded down to $130.

What would I do?

I would buy more… making it a full position.

As an aside, when I initiate a half position, I hope to be wrong.

In other words, I’m hoping for it to fall further so I can establish a full position. Again, I don’t pretend to believe I am buying at the bottom (and nor can I predict when a stock is at the top)

And based on the thousand-plus trades I’ve made over the past two decades – 95% of the time that works over my 3-4 year holding timeframe.

But what does the average investor do?

They see Apple plunging from “~$180 to $130” and they’re selling. They panic and lock in a loss.

Rinse and repeat.

But this approach requires you to be void of emotion. You don’t panic. You don’t get swept up in the market hysteria.

Recall what Buffett said about emotions “corroding your framework”.

It’s also worth repeating the quote from Bernard Baruch

“To break free of this cycle of breakdown and build up, we must free ourselves of man’s age-old tendency to swing from one extreme to the other. We must seek out the course of disciplined reason that avoids both dumb submission and blind revolt”

You train yourself to live with risk, to watch it and study it.

Risk is your friend.

If you’re able to do this – you won’t get bullied by Wall Street – and you certainly won’t listen to the “Monday Morning Quarterbacks” on Bloomberg.

That is, those who pretend to be ‘experts’ after the play has happened.

But should something materially change with my investment thesis (e.g. “Europe and China ban all iPhones due to AI concerns”) – I’m open to changing my mind.

I don’t need to be right and I certainly don’t marry a stock. I have no emotional tie to any position… and it ‘owes’ me nothing.

If circumstances change – then I will change my view.

Which Brings Me to Today

Watching the market behaviour today is nothing we’ve not seen before.

It’s the same script – just in different clothing.

Today that outfit is artificial intelligence (AI). And in another 10 years (or maybe less) it will be something else.

The overwhelming enthusiasm for all things AI is what’s driven the market to recent highs.

Momentum is pushing names like (not limited to) Nvidia (NVDA), Microsoft (MSFT), Alphabet (GOOG), Meta (META), Apple (AAPL), Amazon (AMZN), Broadcom (AVGO) to all-time highs.

And given the concentration risk – it’s carried the Index with it.

That in turn leads to FOMO (fear of missing out) among investors.

You get herd behaviour.

Fundamentals are thrown out the window. From their lens, the bigger risk is “not owning the stock” (at whatever price).

Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.

But it’s not just individuals….

FOMO also impacts institutional investors.

Think about your average portfolio manager who is measured against the benchmark S&P 500.

They are generally paid to outperform the market… otherwise why are you paying them?

Now given the stock market’s recent performance is increasingly being driven by a small group of tech stocks, they have no choice but to participate.

From there, momentum builds.

What happens is we generate a virtuous feedback loop – where fundamentals and risk probabilities are mostly forgotten.

As I mentioned – over 30% of S&P 500 is concentrated in seven companies

It’s what I call a very narrow, tall tower.

But it gets better…

Over 20% of S&P 500 is in three stocks: MSFT, NVDA and AAPL.

And if I look at the Nasdaq – these stocks make up ~50% of the total weight.

So it begs a question…

What if investors or institutions change their mind about these stocks?

What if they wake up tomorrow and think “it’s time to lock in profit – I’m out”

The best analogy here is a crowded theatre where someone yells “fire” with only one exit.

What happens?

Crowded trades are notoriously difficult to exit in an orderly fashion.

For example, if everyone is in a handful of stocks, who is left to buy them if they fall?

But it’s not just these stocks…

When you have a large percentage of ETFs holding these names (SPY etc) – which are concentrated by proxy – the pain spreads like fire.

What do you do?

Take insurance.

You can either lower your risk by choosing a combination of

(a) selling some of your positions; and/or

(b) buying put options (which are cheap – given volatility is extremely low)

This game is about managing risk and limiting your downside.

It’s asking the question of “what could I potentially lose”?

Let’s finish with a quick review of the broader Index…. as I think the risks are to the downside (not the opposite)

S&P 500 – Risk to the Downside

June 22 2024

From a technical lens – the market is extended:

- The weekly RSI trading above 73; and

- The price meaningfully extended above the 35-week and 200-week EMAs

For those who are new to the blog (or learning about the game of asset speculation) – I’m never adding to positions when I see the RSI in this zone.

If anything – this is a warning to take partial profits (or as a minimum buy some protection).

We also see the price retracing to around 61.8% to 76.4% outside the pullback we saw over March and April. Often this is where we will see some resistance.

Finally, we see negative divergence with the weekly MACD. That means we see the MACD making lower highs whilst the price is making higher highs. Ideally we want these two signals to align.

Divergence is a signal momentum is starting to wane.

In summary, technically I expect a pullback.

Now for clarity – the market could pull back ~10% and still be bullish.

That kind of retracement would be very healthy… and I would be a buyer closer to the 35-week EMA.

At present, that is in the zone of 4800 to 5000.

If I remove my technical hat – fundamentally the Index does not offer compelling value.

Again, look no further than the concentration risk.

For example, with 30% of S&P 500 concentrated in seven companies, it’s little wonder the market is trading at forward PE of 22x

If earnings are to come in at $245 per share (which assumes 12% growth year-on-year) – 5464 / $245 = 22.3x

But with AI stocks commanding forward multiples in excess of 30x to 50x (in the case of NVDA) – that’s aggressive in any market.

Putting it All Together

Howard Marks once said that “the superior investor is mature, rational, analytical, objective and unemotional”

I also think they approach things from the lens of “what could they lose” vs what they could gain.

Buyers today are viewing things through the prism of hoping another buyer comes along and is willing to overpay.

And that can work for a while.

But I would argue a strategy based on that is not dependable.

It’s far better to own an under-priced asset which are likely to move back to fair value (and I’ve identified several the past few weeks) – that it is to hope to sell to a bigger fool.

What we see today in the market is not new… it’s not ‘different this time’.

For clarity, AI will change many of the things we do.

No doubt. It’s transformative tech.

Repeating what I said a year ago “we are re-wiring tech – which could result in one of the more important paradigm shifts (in tech) since the mobile phone”

I work on this tech every day of the week at Google (GenAI)… and have for many years.

But I also know it’s a tool…

It does not render the old rules of investor behaviour obsolete.

Fear and greed will not change.

Bad investors will likely make (big) investing decisions that simply extrapolate from the trends they see in the market.

And they will fail to dimension the risks.

Trees don’t grow to the sky and few things go to zero.

In closing, the most dangerous thing you can do is buy something at the peak of its popularity. At that point, all that is favourable about the stock has been factored in to the price.

When that happens, there are no new buyers left.

That’s when someone in the cinema yells “fire“.