- Outlining the “great crash” of 2023

- Could higher bond yields give the Fed scope to sit tight?

- One chart which may auger well for lower yields next year

If you had exposure to bonds at the start of this year – it’s been painful.

In fact, we have not seen a rout in bonds this large in many decades.

Fortunately I avoided bonds up until last month.

My expectation was yields were due to rise – meaning bonds would trade lower.

However, yields are now closer to what I think could be fair value.

Therefore, I’m okay now gradually taking a long position (especially at the shorter-end)

However, I think it’s also worthwhile chipping away at the long-end (which I’ve also been doing).

Call it taking a barbell approach.

Before I explain why I think bond prices are likely to rally next year (yields will fall) – some helpful perspective.

The Real ‘Pain Trade’

As I say, it’s been a horrible 3-years for bond / fixed income investors.

In short, they have been slaughtered as yields shot higher.

For example, losses in long-maturity bonds (e.g. greater than 10 years in duration) are close to historical levels.

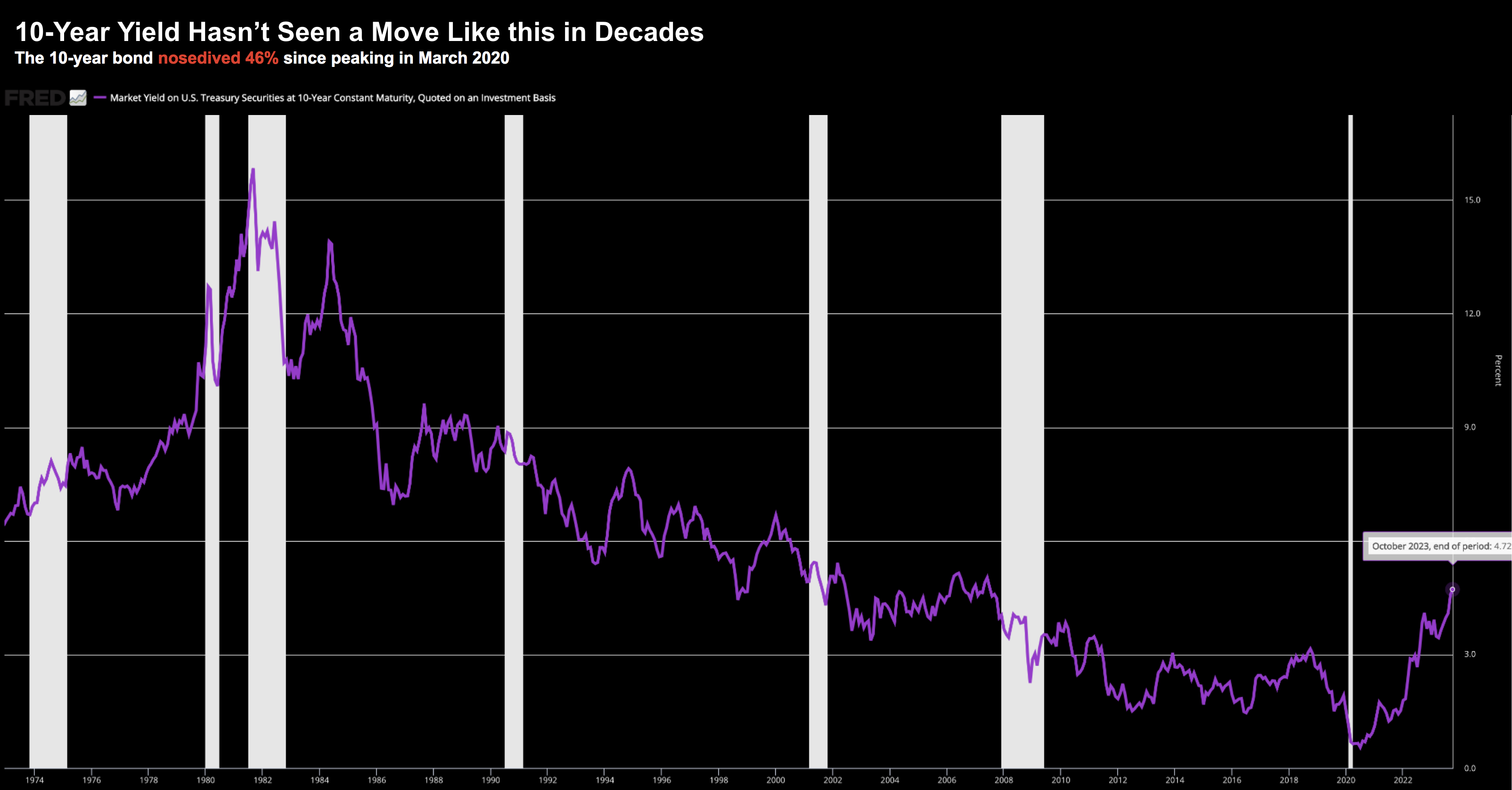

Consider the all-important US 10-year treasury…. an asset which underpins every financial asset.

It has plunged 46% since peaking in March 2020

Put another way, these yields went from ~0.5% at their lows to ~4.8% last week (as bond prices trade inversely to their yields)

October 9 2023

What we’ve seen in the bond market is one of the most severe market crashes on record.

As an aside, this is part of the reason (not the entire reason) banks like Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic no longer exist.

As a result of exceptionally poor risk management – they were forced to sell ‘hold to maturity’ bonds – resulting in their bankruptcy.

I digress…

But it’s not just the 10-year…

30-year bonds have plunged ~53%.

As a parallel, the equity market crashed 57% during the 2007-2009 financial crisis.

That gives you a sense of the devastation.

I raise this because the crash in longer-dated Treasury bonds has a cascading effect on all other financial markets.

Why?

For the simple reason borrowing costs increase.

And this is why we hear language from Fed Reserve officials suggesting higher borrowing costs (from the bond market) may give them room to sit on their hands.

Two Federal Reserve officials suggested Monday (October 9th) that the central bank may leave interest rates unchanged at its next meeting in three weeks because a surge in long-term interest rates has made borrowing more expensive and could help cool inflation without further action by the Fed.

Since late July, the yield, or rate, on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note has jumped from around 4% to about 4.8%, a 16-year high.

The run-up in the yield has inflated other borrowing costs and raised the national average 30-year mortgage rate to 7.5%, according to Freddie Mac, a 23-year high.

Business borrowing costs have also risen as corporate bond yields have accelerated.

Philip Jefferson, vice chair of the Fed’s board and a close ally of Chair Jerome Powell, said in a speech Monday to the National Association for Business Economics that he would “remain cognizant” of the higher bond rates and “keep that in mind as I assess the future path of policy.”

This is a point I made only last week… the bond market is finally doing the work the Fed always intended.

For those less familiar with monetary policy – the Fed only controls the very short-end.

The market controls the long-end (when central banks are not intervening via emergency measures such as “QE”)

Now one sector feeling the “pain” of higher yields are banks.

In fact, we will hear just how much pain at the end of this week when they report (something I’m looking forward to)

Bank stocks are at multi-year lows – trading well below book value in many cases (e.g., BAC, WFC and C) because lenders rely on low-cost borrowing to fund their operations.

Some hedge funds run a similar model.

But as borrowing costs rise – banks and other financial institutions – can face a negative impact on profitability.

Have We Seen the Top in Yields?

The 2023 losses in long-maturity debt have now exceeded the previous largest slump in 1981.

In the early 1980s – the surge in bond yields were the result of the Fed’s efforts to combat inflation which exceeded 16%.

What’s more, the losses this year also surpass the average decline of 39% seen in seven US equity bear markets since 1970

They say history does not repeat – but it sure does rhyme!

As I indicated earlier, longer-dated bonds appealed to investors (and banks like SVB and First Republic) — as the Fed spent ‘years’ cutting borrowing costs to zero (largely to fund excessive government spending).

As bond yields went lower – bond prices surged.

However, as government borrowing and spending soared – combined with COVID related supply-chain issues – inflation surged to levels not seen in 40 years.

We had far too much money in the system chasing too few goods.

The question is whether the pain is over for bond investors?

That’s very hard to know… maybe not yet.

However, I want to offer a chart which could offer insight:

October 9 2023

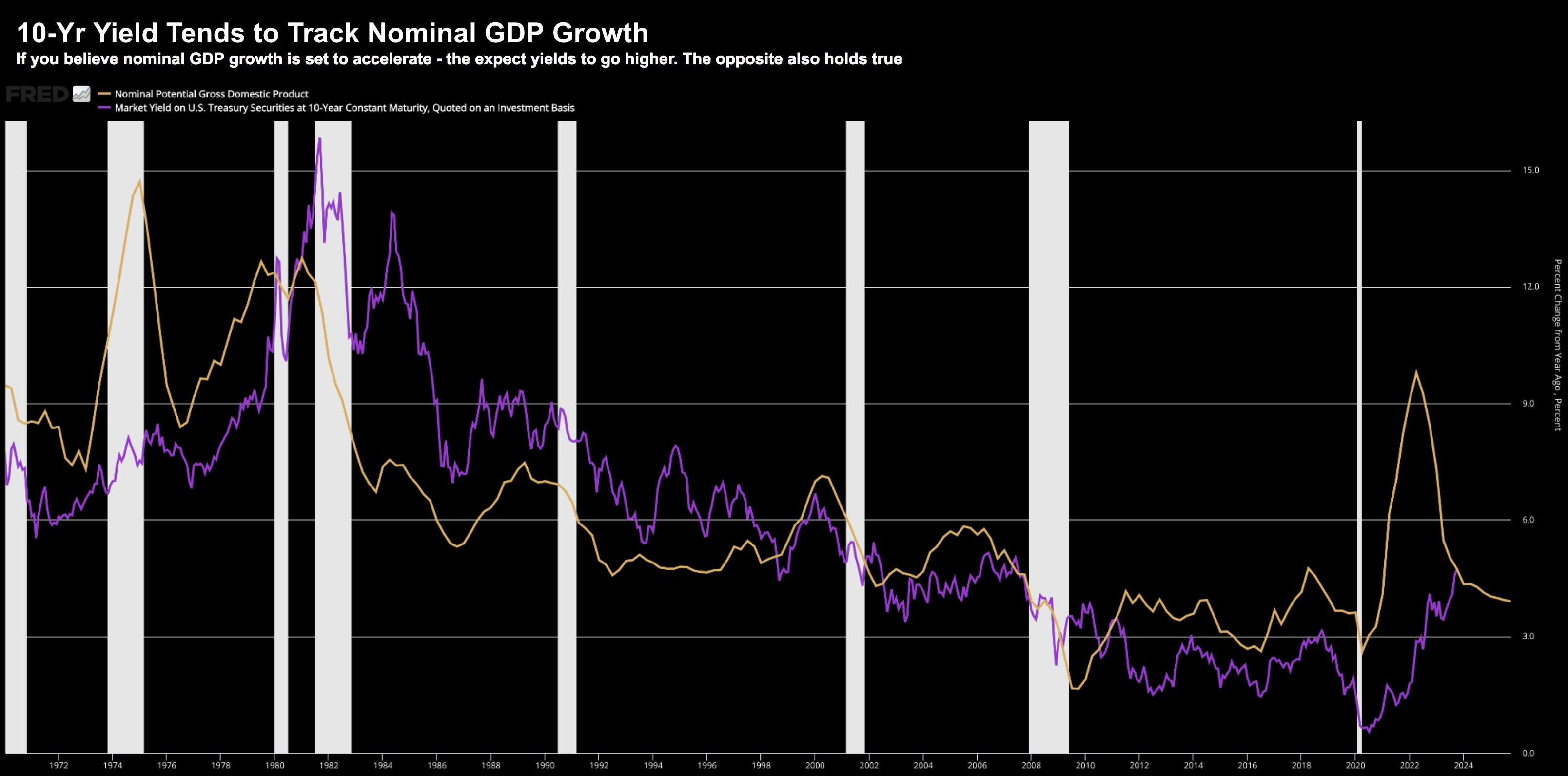

This 50-year chart shows nominal GDP growth (orange) against nominal 10-year yields (purple)

Whilst the correlation is not 100% – it’s very consistent.

In general, the yield on the 10-year will roughly track what we find with nominal GDP growth.

And whilst at times they will over-and-under shoot – the direction is largely aligned.

Therefore, the question you need to ask is where do you think nominal GDP growth will be next year?

For example, if you think growth is going to accelerate, expect yields to remain high.

On other hand, if you think growth is likely to contract (as I do), then bond yields are likely to trade lower.

For example, the 10-year could trade closer to 3.50% than say 5.00%.

And whilst there are a host of other factors at play (e.g. whether the Fed will continue to raise rates) – what we find with the growth outlook has a major bearing.

If you are bullish on growth – sell bonds.

Putting it All Together

For me, the nail in the “bond coffin” was July 31st 2023.

As it happened, this date coincided with the market top of this year (the week of July 24).

On that day, Janet Yellen told us the government was about to increase treasury issuance by one-third more than expectations.

- During the July – September 2023 quarter, Treasury expects to borrow $1.007 trillion in privately-held net marketable debt, assuming an end-of-September cash balance of $650 billion.

- The borrowing estimate is $274 billion higher than announced in May 2023, primarily due to the lower beginning-of-quarter cash balance ($148 billion) and higher end-of-quarter cash balance ($50 billion), as well as projections of lower receipts and higher outlays ($83 billion)

- During the October – December 2023 quarter, Treasury expects to borrow $852 billion in privately-held net marketable debt, assuming an end-of-December cash balance of $750 billion.

This tsunami of debt sent bond yields soaring – and put a lid on equities for the balance of the year.

As I keep saying – stocks will find it hard to rally opposite higher yields.

Now at the same time – we also had pressure on the demand side.

For example, we had quantitative tightening (QT) – meaning the Fed was not going to step in and buy debt.

Their job was to take money out of the system – not add to it!

In addition to QT – we had other countries managing their relative currency’s strength by selling US debt (specifically Japan).

In short, we had massive supply for debt with very few buyers.

It was a new supply-demand dynamic – which was only going to send yields higher.

But…

At some point (and it’s not in the next few months) – bond yields will reflect the weaker economy.

We have seen that script play out the same way for 50 years.

My conviction for a recession next year has only increased the past few weeks as I watch the un-inversion of the 2-10 yield curve (i.e. the bear steepening)

If I’m right (and I may not be) – bond yields will fall next year – meaning buyers of bonds at today’s levels potentially stand to make meaningful capital gains.

What’s more, further losses on bond prices are partially offset by the (higher) yields they are locking in.

That doesn’t mean yields cannot continue to rally between now and then… they can.

But at some point – should GDP growth weaken – yields will fall.

And that will be punctuated by the Fed saying “they’re done”

To that end, let’s see how CPI comes in later this week.

Expect Core to trade with a 4-handle.