- How the Fed thinks about inflation reports

- Why I’m not banking on rate cuts in 2023; and

- What the Fed need to do to bring inflation down

When reviewing December’s inflation print earlier this week – I said there was something for both the bulls and the bears.

For example, the market was quick to cheer the 6.5% headline CPI.

“Inflation is coming down… expect the Fed to cut” … or something like that.

Should we? Why?

For example, where specifically is inflation coming down? And if it’s coming down, is it in the areas the Fed is targeting?

And at what velocity?

We need to be crisp in our language when using broad terms like “inflation”… as not all inflation is equal.

Let me explain…

Inflation is like an Onion

This weekend I read a terrific essay from John Williams – President of the New York Fed.

He offers a useful analogy on how the Fed thinks about inflation.

What struck me immediately is this is not how the market sees things (not yet anyway).

Williams starts by saying there are many sources of high inflation across the globe.

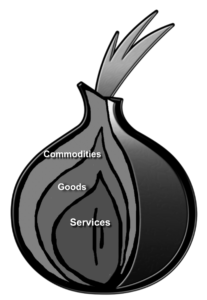

However, in every instance, inflation consists of three distinct layers:

The outermost layer consists of prices of globally traded commodities—such as lumber, steel, grains, and oil. When the global economy rebounded from the pandemic recession, there was a surge in demand for these critical goods, leading to sizable imbalances between supply and demand and large price increases. Then, energy and many commodity prices soared again as a result of Russia’s war on Ukraine and consequent actions. Skyrocketing commodity prices led to higher costs for producers, which in turn got passed on as higher prices for consumers.

The middle layer of the inflation onion is made up of products—especially durable goods like appliances, furniture, and cars—that have experienced both strong demand and severe supply-chain disruptions. There were not enough inputs to manufacture products, which meant not enough products to sell—all at a time when demand has been sky-high. This imbalance contributed to outsize price increases.

If we continue paring the onion, we’ll reach the innermost layer: underlying inflation. This layer is the most challenging of the three, reflecting the overall balance between supply and demand in the economy and the labor market. Prices for services have been rising at a fast clip. Measures of the cost of shelter, in particular, have increased briskly, as an earlier surge of rents for new leases filtered through the market. And widespread labor shortages have led to higher labor costs. And this is not limited to a few sectors—inflation pressures have become broad-based.

John Williams’ Inflation Onion

The mistake often made is anchoring too much on the outer and middle layers.

For example, let’s start with Williams’ outer layer.

Commodity prices peaked last year and have come down considerably. Whilst not exhaustive – here’s an example:

- Copper down 16% from its peak;

- Crude is down 39% from its peak ($130/b March 2022); and

- Lumber – down 80% – peaking at $1,711 – now ~$344

Now on the assumption that global growth continues to slow (opposite tighter monetary policy from central banks) – this will likely keep downward pressure on prices.

As an aside, China’s reopening has some suggesting demand could increase (pending subsequent waves of COVID etc). But that’s subject for another blog (I have my doubts whether China’s reopening will be as fast / smooth as the market assumes). I digress…

With respect to the middle layer – goods prices – they are also showing signs of coming down from peak levels.

- Used cars and trucks are down ~9% YoY

- New vehicles are down 0.1% MoM; and

- Many other goods are generally trending lower (or near flat MoM)

Much of this is due to the significant improvement in global supply chains.

For example, there are no longer ships stalled at ports in California.

Williams states that the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, developed by the New York Fed, shows that global supply chain disruptions soared to unprecedented levels late last year. Since then, this index has retraced about three quarters of that rise.

He argues the combination of waning global demand, improving supply, and falling import prices from the strong dollar points to slowing core goods inflation going forward.

However Williams also believes that lower commodity prices and receding supply-chain issues will not be enough to get inflation back to the Fed’s 2.0% objective.

The innermost layer – the core – is where the hard work lies.

Overall demand for labor and services still far exceeds supply, resulting in broad-based inflation, which will take longer to bring back down.

That said, things are slowly moving in the right direction:

Growth in rents for new leases has slowed sharply recently, implying that average rent growth and housing shelter price inflation should turn back down.

We’re also seeing some signs that the heat of the labor market is starting to cool, with quits and job openings declining from the high levels of the spring, along with indicators of slowing wage growth.

Don’t Bank on Rate Cuts in 2023

At the time of writing, the market is pricing in two rate cuts before the end of this year.

Further to my preface, the market immediately started discounting further rate hikes on news of December’s 6.5% headline CPI.

For example, the best real-time proxy is what we see with the US 2-year treasury – trading at 4.23%

That is in the realm of 75 basis points lower than where the Fed tells us they’re going.

I talked about the clear disconnect recently – suggesting one of two outcomes; i.e., either

- The Fed’s terminal rate is going to be a lot lower they expect; and/or

- The economy is going to be much weaker.

Take your pick.

But let’s try and tie this back to the (core) inflation discussion above…

If you listen to any Fed member speak today – if there is just one thing they all agree on – it’s how tight the labor market is.

You will hear varying opinions on what the terminal rate needs to be or what they see in terms of growth etc – but they are unified on the concerns with the labor market as it pertains to inflation.

To that end, Chair Powell has been very clear on the specific mechanism they are targeting (i.e. the core)

And it’s the (potential) inflation inertia which has Powell concerned.

For example, the latest employment report told us the labor market is still running hot.

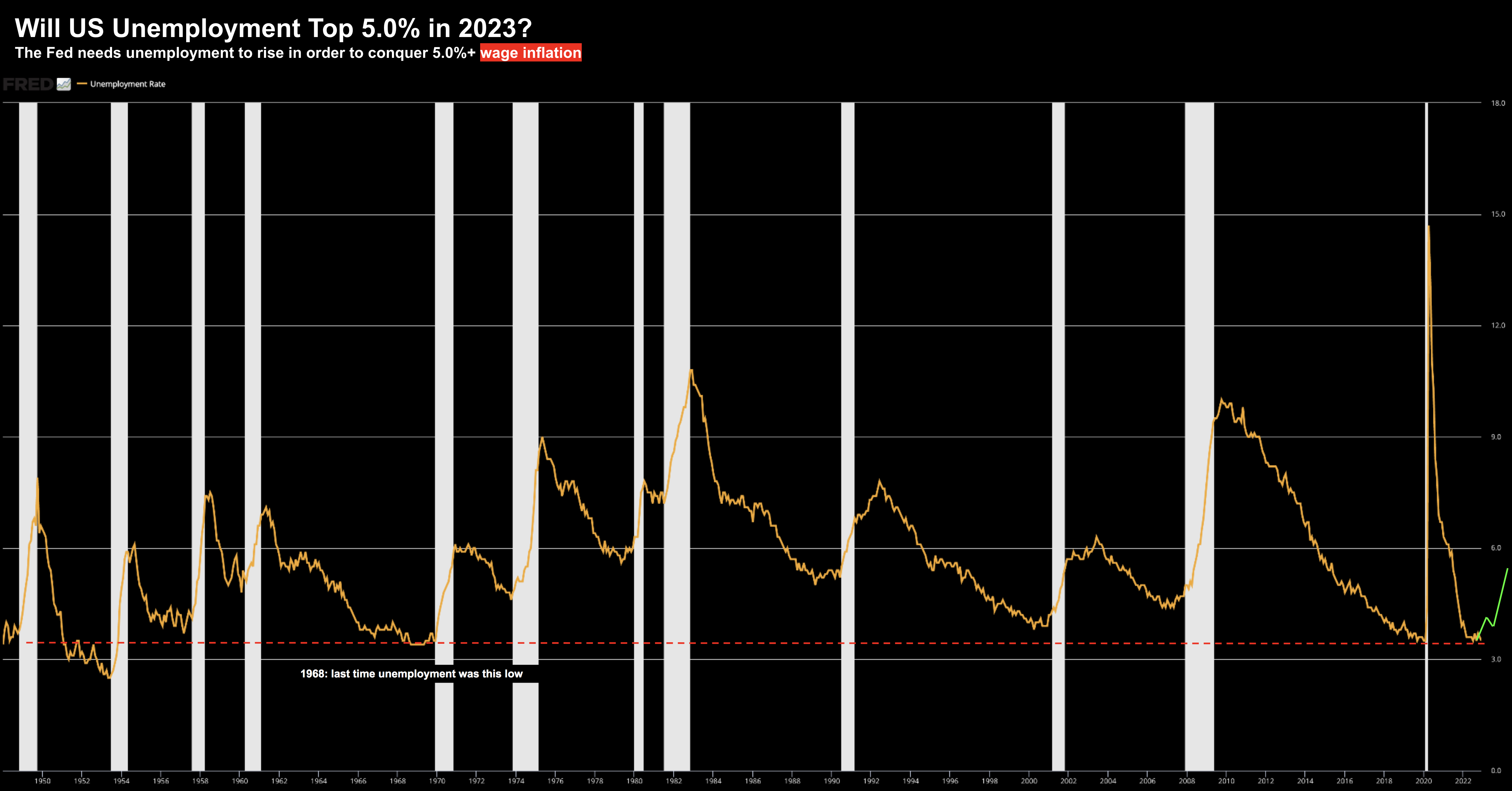

Unemployment remains ~3.5% and wage inflation is close to 5%.

By way example, December we saw ~223,000 jobs added – driving the unemployment rate at a 50-year low.

Jan 14 2023

Now given what we know about economics – if the labor market continues to remain this tight – eventually we will see wage pressure.

It’s Econ 101.

From the perspective that aggregate demand has momentum — that’s going to put further pressure on resources — in turn driving up wages.

And whilst that pressure may not show in goods prices every other month… over time it will if it becomes too entrenched.

Here’s an example:

When wages go up, the supply curve shifts upward.

This has the effect of raising prices whilst at the same time – potentially reducing output.

And that’s the (wage inflation) spiral the Fed is willing to go to any length to avoid (recession or otherwise).

This is why I lean towards the Fed pushing the target rate closer to 5.00% (perhaps 5.25%) and keeping it there.

Put another way, it’s arguably less about ‘how high’… but more ‘how long’.

But that view is very much at odds with the bond (and equity) market.

Markets do not see the Fed getting to 5.0%.

And if they do… they see them cutting not long after.

For example, the bulls will be quick to counter that we’ve seen reduced inflation pressure for six months in a row (most notably the ‘outer two layers’)

That’s true (for reasons Williams outlined)

But…

We need to balance that view with the Fed’s objective of 2.0% inflation will be achieved over the medium term (and not simply the next ‘three or six’ months).

In other words, we need to see far more progress at the ‘inner layer’ before we reach any conclusions.

Putting it All Together

The good news is month-over-month we’re likely to see the ‘outer two’ inflation layers continue to decrease.

Commodities and goods prices will continue to moderate (all going well).

However, there’s also a chance the market will treat that as inflation falling.

What’s warranted is a closer look at the onion at its core; i.e., the mechanics.

What do we see with inflation inertia and its velocity?

This is the mechanics which will dictate Fed’s policy in the month’s ahead…. not what we see with commodity and goods prices.

And if employment continues to remain strong – there’s no reason for the Fed to pivot to cut rates.

From mine, that’s not a bad thing.